UNIT 8: GERMAN AND BELGIAN COLONISATION (1897-1962)

Key unit competence: By the end of this unit,the learner should be able to explain the causesand impact of German and Belgian colonisation 1. Find out the meaning of the word “colonization” from the

1. Find out the meaning of the word “colonization” from the

Internet and the dictionary. Write the meaning in your notebook.

2. Identify the nationalist of first Europeans to come in Rwanda.

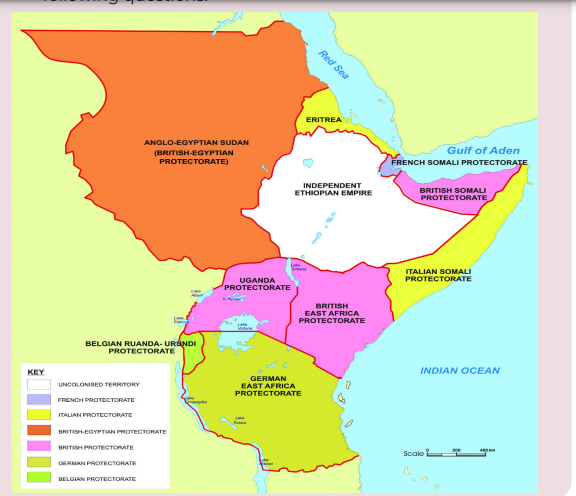

3. Copy the following map in your notebook then answer the

following questions:

i. Identify the current names of the countries on the map.

ii. Write down the countries that colonised the ones you identified

in question (i) above.

iii. Estimate the period under which colonial administration in each

of the shown countries ended.iv. Present your findings in class for further discussion.

Introduction

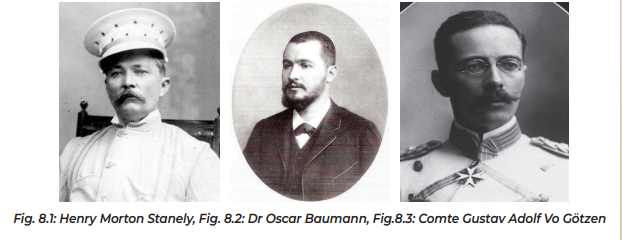

German colonisation of Rwanda began with the coming of European

explorers to Africa. This was around 1880, when Africa experienced an

increase in European explorers. One of the factors that drove explorers

to Africa was the desire to discover the source of the river Nile. From 1856,

the Geographical Society of London had started to organise regular

exploration missions to discover the source of that river. Some of the

explorers who visited Rwanda include Sir Henry Morton who reached

Akagera River in 1875, Dr Oscar Baumann who arrived in southern Rwanda

on the 11th of September 1892. and Comte Gustav Adolf von Götzen who

entered Rwanda after crossing Akagera River above Rusumo Falls. Von

Götzen was guided by Prince Sharangabo, the son of King Rwabugiri. He

was later received by King Kigeli IV Rwabugiri on May 25th,1894 at Kageyo

in Kingogo in present day Ngororero Distric, western province.

Von Götzen was followed by a second German mission led by Captain

Ramsay who arrived in Rwanda on March 20th,

1897 during the reign of King

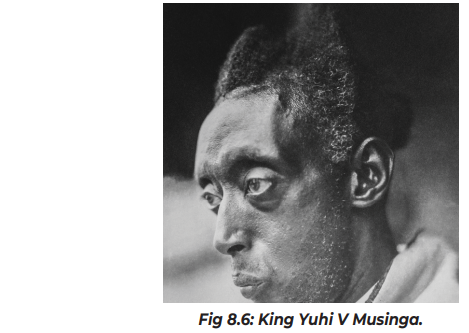

Yuhi V Musinga. During this visit, Captain Ramsay gave King Musinga the

Germany flag as a symbol of German authority. From then, the German

occupation of Rwanda became a reality. Rwanda-Urundi became a

region with the capital in Usumbura (Bujumbura). This region was placed

under the control of Captain Bethe who arrived in Rwanda in March 1898 atthe royal residence of Gitwiko in the present day Kamonyi District

8.1. Causes of German and Belgian colonization in Rwanda

The following are some of the factors that made Germans and Belgians

move into Rwanda:• Industrial revolution in Europe• Investment of surplus capital• Rwanda as a source of raw materials• Need for market.Discuss how each factor led to colonisation of Rwanda. Make notes forpresentation in a class discussion.

The main causes of German and Belgian colonization are:

a) The industrial revolution in Europe.

The industrial revolution begun in Britain in the second half of the 18th

Century and thereafter spread in other countries such France, Germany,

Belgium among others. It led to an increase in demand for raw materials

needed by the industries for further production. As production increased,

so was the need for an expanded market for the manufactured products.

European countries had to look up to Africa to provide the much-neededraw materials and market.

b) Rivalry among European countries.

Rivalry between European countries also contributed to colonisation

of African countries. Competition to produce more and supply more

contributed to the rivalry among European powers such as Britain and

Germany. Both had to protect their overseas territories because theterritories supported the entire industrialisation process.

Continued production and supply of manufactured goods led to massive

profits to bourgeoisies who owned the factories. These wealthy people

wanted to invest their surplus income outside their countries because of

competition and reduced investment opportunities their countries offered.This factor pushed them to look for opportunities as far as into Africa.

c) A source of raw materials and cheap labour.

European colonies were able to acquire raw materials (cassiterite,

wolfram and cash crops) for use in their home industries and cheap labour.

The labour was also used in neighbouring colonies to the benefit of the

colonisers. For example, Belgians acquired cheaper labour from Rwanda for

use in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Africans helped in the collection

of ivory and rubber and extraction of minerals in the upper Congo basin

for sale elsewhere in world. In addition, several major Belgian investment

companies pushed the Belgian government to take over the Congo and

develop the mining sector. This sector required local labour which wasregionally acquired.

d) Prestige and geostrategic interest.

Some European nations competed to assert themselves as major

superpowers. For example, the newly formed nations of Germany and

Italy wanted to catch up with England, France and other established

colonial powers. More colonies for these countries were a sign of a nation’s

strength. In addition, European countries which had already established

themselves in some African countries felt that it was necessary for themto acquire more countries for geostrategic reasons.

e) Need to spread Christianity.

The colonisation of Rwanda was a way to spread Christianity by European

missionaries. The missionaries were mainly Roman Catholics andAnglicans. They later established their churches and missions in Rwanda.

f) Need to promote western civilization.

The Germans and Belgians considered Rwanda to be backward and

therefore had a strong desire to civilise it socially, economically andpolitically.

g) The role of the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference.

During this time, African countries were distributed among European

countries where Rwanda was given to Germany. This accelerated andcontributed to the colonisation of Rwanda.

Write an essay on the causes of German and Belgian colonization in

Rwanda. Present your findings in class.

8.2. German administration and its impact in Rwanda.

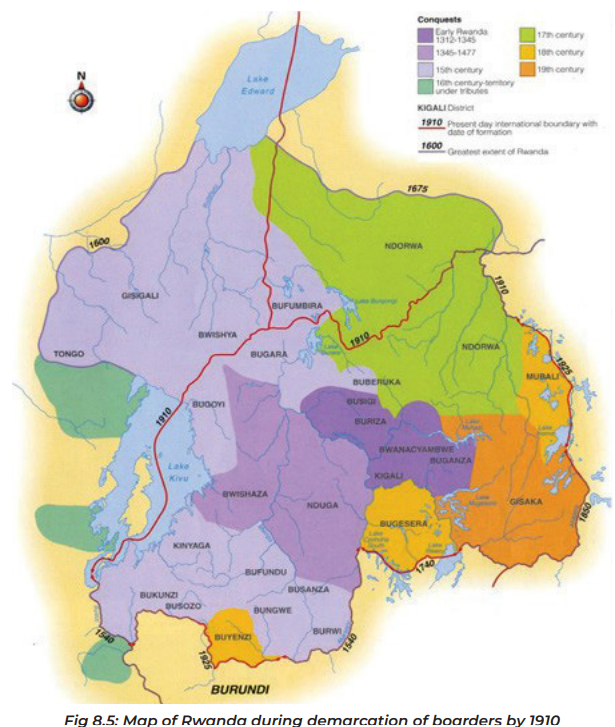

1. Draw a sketch of map of Rwanda and show its boarders by 1910.

2. Explain the causes of revolts against Musinga during the German

rule.

3. Identify regions which revolted against Musinga and the attitude of

the Germans towards these revolts.

4. Explain the characteristics of the system of administration practiced

by the Germans.5. Discuss the impact of those revolts on Rwanda.

8.2.1 German administration in Rwanda

In Rwanda, Germans used indirect rule. This form of administration

used traditional leaders to administer on behalf of the Germans. It also

respected and maintained local culture. The implementation of the

German rule was to be attained through the Military Phase and Civil

Administration Phase.

a) Military Phase (1897-1907).

This phase was characterised by occupation of Rwanda between 1897

and 1907. At the same time, the German government gave support to

the local leaders to stop several revolts. Therefore, the military post at

Shangi and Gisenyi were only meant to bring people in those areas

under German rule and under the local Rwandan regime headed byKing Musinga.

b) Civil Administration Phase (1907-1916).

The administrative services were transferred from Usumbura to Kigali

and Richard Kandt was made the first Resident of Rwanda. Kandt was

given the responsibility of establishing the civilian rule, conducting census,

collecting taxes and creating a police force. Kigali was founded as the

imperial residence. In addition to that, the German government provided

military support to the local authorities to stop several uprisings like those

staged by Ndungutse and his allies, Rukara and Basebya. Ndungutse,

whose real name was Birasisenge, wanted to declare himself a legitimate

king after pretending to be the descendant of Mibambwe IV Rutarindwaand Muserekande nicknamed “Nyiragahumuza.’

The following were the causes of rebellions in northern Rwanda:1. There was need to recover lost glory by the people which had beentaken over by the royal court of Rwanda.2. They were also subjected to forced labour introduced by theGermans during the fixing of frontiers in 1910. To them, this wasunfair, and therefore made them revolt.3. The Germans forced people to supply them with food. This annoyedthem, causing a revolt not only against the German rule, but also tothe central authority headed by the king.Basebya was one of the rebellion leaders. He was a son to Nyirantwari of

Rugezi and a member of the Abashakamba militias of Kigeli IV Rwabugiri.

With his group of warriors known as Ibijabura, Basebya conquered Buberuka,the whole of Bukonya (Gakenke District) Kibali (Gicumbi District).

With three conquered regions, Musinga’s power was seriously challenged.

Following the expedition of Ndungutse in Bumbogo and Buberuka, the

acting Resident representative Lieutenant Godivius, nicknamed Bwana

Lazima, decided to fight against the opposition. Ndungutse and Rukara

were killed a few days later. Rukara was hanged. Basebya, who wasarrested by chief Rwubusisi, suffered the same fate on May 5th, 1912.

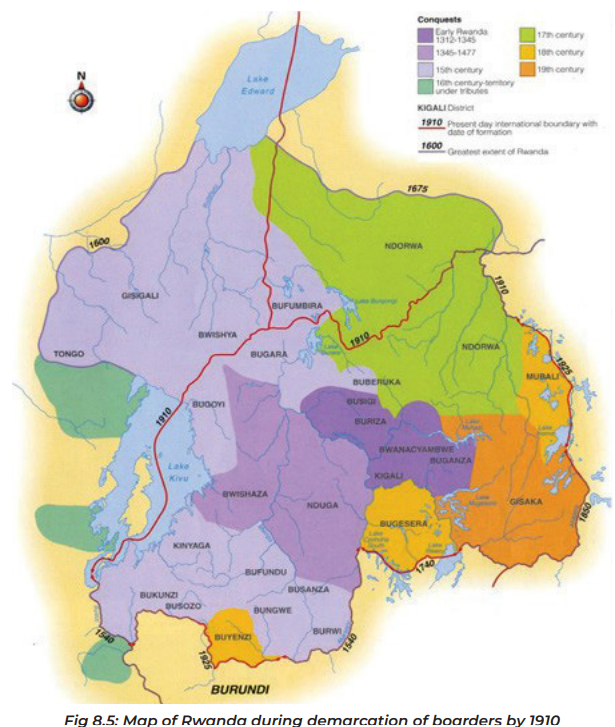

Another major event that took place during this phase was the

demarcation of Rwanda’s borders. This was done on 8th February 1910

during a conference held in Brussels between Belgium, Germany and

Britain. Rwanda was limited in the northern and western frontiers. The

redrawing of the borders was done on a map.

In this exercise of re-fixing its borders, Rwanda lost one half of its actual

size as follows: Ijwi Island, Bwishya and Gishari were annexed to Belgian

Congo while Bufumbira was annexed to Uganda. Unfortunately, thefixations did not put into account the structure of the local population.

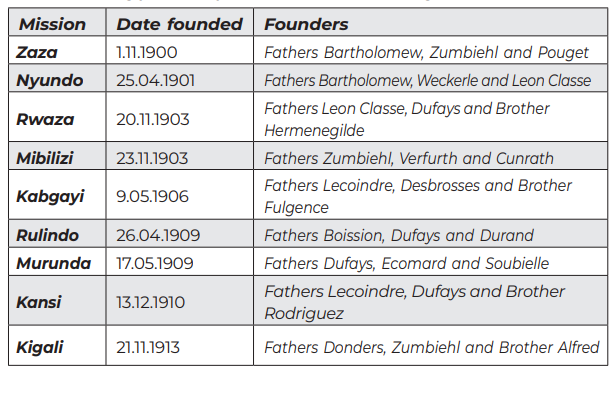

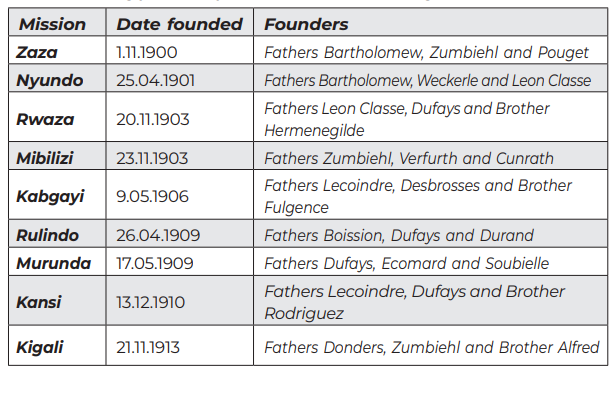

The coming of missionaries

Christian missionaries came just after the coming of German administrators

to Rwanda. The first religious groups to emerge during the German rule.

Was the Catholic Church, Islam and Lutheran Protestantism. More religious

groups came in during the Belgian rule, for example, the Adventists in1919, Anglicans in 1918, Pentecosts in 1941 and Methodists in 1943.

i) Roman Catholic missionaries.

The White Fathers introduced Roman Catholicism in Rwanda. They were

led by the Apostolic Vicar of Southern Nyanza (Tanzania), Bishop Joseph

Hirth. They were part of the Société des Missionaires d’Afrique,” foundedin 1868 by Archbishop of Algiers, Cardinal Charles Lavigerie.

He came to Rwanda from Shangi. Later, he arrived at the royal court

in Nyanza on February 2nd,1900, accompanied by Father Brard and

Father Paul Bartholomew, and Brother Anselme. At the royal court, the

missionaries requested for land to settle, and their request was accepted.

The land given to them was at Save in Bwanamukali today in Gisagara

District, Southern Province where they founded their first mission onFebruary 8th, 1900.

In the following years, they established the following other missions:

ii) Protestant missionaries

Protestantism was introduced in Rwanda by the missionaries of the

Bethel Society. The first pastor to arrive in Rwanda was Emmanuel

Johanssen who came from Bukoba in Tanzania. As for German Protestant

missionaries, they were received at the royal court in Nyanza on 29th July

1907. They founded their first missions at Remera-Rukoma in 1912, Kilindain 1907 and Rubengera in 1909 among others.

There was also the first Seventh Adventist Church that was established at

Gitwe by Pastor Meunier in 1919. In the years that followed, other missions were

established at Murambi in Buganza today in Gatsibo District, Eastern Provinceand Rwankeri in Buhoma today in Nyabihu District, Western province.

iii. The First World War in Rwanda

The First World War that occured between 1914 and 1918 was mainly fought

among European nations. However, its impact was indirectly felt in othercontinents including America, Asia and Africa.

In Rwanda, the Germans fought with Belgians who had colonised Congo

(DRC). The war was intense in Bugoyi in present day Rubavu district in

the northwest region and Cyangugu in present day Rusizi District in the

southwest region in western province. The Germans were the first to begin

the war by attacking Belgian Congo’s Ijwi Island in September 1914. This made

the Belgians to respond by fighting back. Belgians were supported by Britishtroops. The troops were deployed in two directions: Shangi and Gisenyi.

Kigali was finally captured on 6th May 1916 then Nyanza on 19th May 1916.

Later, the Belgians moved on with the war through the Rwandan territory

towards Burundi.During the war, Rwanda did all she could to support Germany. This

support ranged from providing armed warriors called Indugaruga as well assupplying food.

8.2.2. Impact of German colonization in Rwanda.

Their reign was short-lived, from 1897 to 1916. This was hampered by their

defeat in the First World War in Europe and Rwanda respectively in 1916.They made a little impact as discussed below:

a) Demarcation of Rwandan border.

On 14th May 1910, the European Convention of Brussels fixed the borders

of Uganda, Congo and German East Africa. This included Tanganyika and

Rwanda-Urundi. It is until 1918, under the Treaty of Versailles, that the former

German colony of Rwanda-Urundi was made a Belgian protectorate by

League of Nations. This led to demarcation of Rwanda’s borders. The fixing

was done using a map. Rwanda lost parts equal to one and half of its actualsize.

b) Support to King Musinga (Mwami).

The Germans settled and helped the Mwami (King Musinga) gain

greater nominal control over Rwandan affairs. They fought rebellions and

defended his rule. The Germans used indirect rule in Rwanda that gavepower to the king and local authorities.

c) Opening of Rwanda to outside world.

Dr Oscar Baumann came to Rwanda in September 1892. He was followed

by Von Götzen in 1894. The latter led an expedition to claim the interior

of Tanganyika colony. Thereafter, German colonialists and, missionaries

arrived in Rwanda. Therefore, the initial visits of Baumann and Von Götzen

is seen as the beginning of the opening up of Rwanda to the outsideworld.

d) Integration of Rwanda in world economy.

German colonisation of Rwanda led to the export of large quantities

of hides and livestock. The exportation was mainly oriented towards

European countries. This initiated a market economy in Rwanda.

e) Introduction of money.Money was introduced in Rwanda during the German colonisation of

Rwanda. People used coin money, heller and rupees. Many Rwandans saw

money as a replacement for barter trade in terms of economic prosperity

and social standing.f) Introduction of head tax.

German colonisation of Rwanda led to the introduction of the head tax on

male adult Rwandans.

g) Coming of European missionaries.

The German colonisation of Rwanda led to the coming of European

missionaries in Rwanda. Roman Catholic missionaries, led by the White

Fathers, came to Rwanda in 1900. They were followed by the Presbyterianmissionaries in 1907. This promoted Christianity in Rwanda.

Make an essay on the impacts of German colonisation in Rwanda.Present the results.

8.3. Reforms introduced by Belgians.

Using textbooks, internet or other resources,1. Assess the transformations introduced by Belgians in

Rwanda then present your results to the class.

2. Explain the reasons for the deportation of King Musinga in1931. Thereafter, compile an essay for the teacher to mark.

During the First World War I, Germans fought with Belgians in Rwanda.

This led to the defeat of Germans in May 1916. Belgians then officially

took over control of Rwanda from Germans. The Belgian administration

in Rwanda led to a total change in Rwanda’s political, social, economic,cultural and religious sectors.

It is important to distinguish the reforms introduced by Belgians in

Rwanda into three stages of the entire Belgian rule. These are:i) Reforms introduced during the Military Administration (1916-1924)8.3.1: Reforms introduced during the Military Administration (1916 - 1924)

ii) Reforms introduced during the Belgian Mandate (1926-1946)iii) Reforms introduced during the Trusteeship (1946-1962)

After the conquest of Ruanda-Urundi in 1916, German colonialists were

replaced by the Belgian occupational troops. The troops were responsible

for managing the country. The Belgian Military High Commander in

charge was J.P Malfeyt. He was the first Belgian Royal High Commissionerin Rwanda. His residence was at Kigoma in Tanzania.

He was tasked to maintain order and public safety over all the territoires in

Ruanda-Urundi. He was in charge of Belgian troops in the occupation of

Rwanda. He played this role until the end of the First World War.

After the War, Rwanda once again fell under military regime, and was

divided into military sectors. These were Gisenyi, Ruhengeri, Cyangugu and Nyanza.

The military sectors were later transformed into territoires, namely:i. The western territory (Rubengera territory capital)Major De Clerk later was named as Resident in 1917. Later, he was replaced

ii. Northern territory (Ruhengeri territory capital)

iii. The territory of Nyanza (Nyanza territory capital)iv. The Eastern territory (Kigali territory capital)

by F.van De Eede in 1919.

The following are some of the reforms introduced in Rwanda duringthe military administration:

a) Systematic disintegration of the monarchyEach of these reforms has been explained below in detail:

b) Undermining the Mwami’s (king’s) legal power

c) Reduction of the Mwami’s (king’s) political power

d) Abolition of Ubwiru and Umuganura

e) Declaration of religious freedom

f) Abolition of imponoke and indabukirano

a) Systematic disintegration of the monarchy.The relationships of the occupying authorities with the court of the king

were very bad. For example, on 25th March 1917, the General Auditor of

Kigoma was ordered to arrest the king. It is at this time that the RoyalCommissioner, General Malfeyt, decided to send De Clerk as the Resident.

Under De Clerk, the residence of Rwanda was divided into Northern,

Nyanza, Western and Eastern territories. The division was to facilitate

implementation of military orders, food requisition and recruitment of

carriers for the Belgian colonialists. Furthermore, in 1922, the decision

by Belgians that the Resident at Nyanza would assist the Mwami (King

Musinga) in his legal prerogatives was meant to undermine the king’s

legal power.

b) Undermining the Mwami’s (king’s) legal power.The king, before the Belgian occupation, had authority to pass ‘life or

death’ sentence over his subjects. The king was stripped off this right to

determine whether a person would live or be killed because of a crime

committed. Crimes that warranted the death sentence from the king

included murder, fighting with fellow subjects or treason. Without such

authority, the king’s title was reduced to being just but honorary. This,among other reasons, humiliated the king greatly.

c) Reduction of the Mwami’s (king’s) political power.King Musinga was stopped from appointing and dismissing any of his

subordinates without permission of the Belgian High Commissioner or

Resident. Chiefs and Governors of provinces too did not have the right

to dismiss those who worked under them. With time, the final source of

authority became the Belgian administration. Chiefs and their deputies

therefore were required to report to the Belgian administration and notKing Musinga as was the case initially.

Traditional authorities were charged with the following responsibilities:

a) Collecting taxes

b) Mobilising porters and workers on local roads and tracks

d) Abolition of ubwiru and umuganura.

Abiru were officials in Rwandan Kingdom who were in charge of ubwiru

(amabanga y’imitegekere y’igihugu). The traditional institution of ubwiru

played very important roles in the Rwandan Kingdom and to the mwami

(king).

Umuganura (umunsi mukuru wo kwishimira no gushima Imana kubera

umusaruro wabonetse mu mwaka) was meant to thank God for the harvest.

It was also to strategise for the next season, so as to ensure that the harvest

is good. It was celebrated by Rwandans after harvest of sorghum. It was a

very big event in the kingdom as Rwandans celebrated their achievements

in terms of harvest both at the kingdom and family level.

Belgians abolished both the ubwiru and umuganura in a systematic way

to curtail the king’s powers. Eventually, in 1925, the chief of ubwiru who was

called Gashamura was exiled in Burundi. The Resident communicated to

King Musinga that umuganura had been abolished.

e) Declaration of religious freedom.In traditional Rwanda, the king was not only an administrative leader but

also a religious leader who was an intermediate between God (Imana) and

Rwandans. This made Rwandans to consider their King as God and would

refer to him as Nyagasani (meaning God). However, with the influence of

the Catholic Church and the administration of the Belgians in 1917, KingMusinga was forced to sign a law accepting freedom of worship.

From then, the King had no option but to allow religious freedom that

would favour the Catholics. Therefore, the royal power was separated with

religion because the King had just been forced to forego his religiouspowers.

f) Abolition of imponoke and indabukirano.

Indabukirano were gifts given to the chief after being nominated and

coronated to the position. The gifts included items like cows and beers

(indabukirano). Such was meant to show loyalty to him by his subjects. It

was also to enable the new chief to cope with the new lifestyle, to showhappiness and to congratulate the new chief.

Imponoke was a sign of compensation to the chief usually after a heavy

loss of cows, especially due to diseases or being struck by lightening. This

was a sign of active bystandership to the chief by his subjects. Generally,

to the chief, it was a way of compensating him for the loss of cows and to

enable him to continue living within the lifestyle he was used to before the

loss. It was one of the ways Rwandans used to show concern for others inthe society.

The practice of imponoke and indabukirano were abolished by the Belgians

when they took over the administration of Rwanda. This was aimed at

weakening the influence of the king over his subjects. It was also to help

the Belgians remain with monopoly of power. The expected end result

was to reduce the belief in traditional practices where Rwandese haddeep attachment.

A mandated territory is a country or territory that is governed by another8.3.1: Reforms introduced during the Belgian Mandate (1926-1946)

country based on the authority given by the League of Nations. The

mandate may imply different forms of government varying from directadministration by the other country to being self governing.

1. Political reforms (1926-1931)

Mandated territories were introduced in 1919. In 1922, the League of Nations

gave Belgium a mandate over the territory of Ruanda-Urundi. Belgium

was to administer and control the territory while respecting the freedom

of religion and stopping slavery. The mandates were divided into three

classes, A, B and C, according to the presumed development of their

population. Rwanda was put under the mandate B with Belgium as amandatory power.

This mandate was approved on 20th October 1924 by the Belgian parliament.

For this reason, from 1916 – 1924, Rwanda was called “a territory under

occupation.” However, it was officially known as a “territory under mandate

B.” Other countries in this category were Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Togoand Cameroon.

The administrative reforms initiated by Belgian authorities started in

1926 and brought with it a number of changes where Rwanda-Burundi

was joined to Belgian Congo in terms of administration. This meant that

Congolese colonial laws were applied to both countries.The following were the other reforms in administration:

1.1. Mortehan reforms (1926-1931)

Between 1926 and 1932, the Resident of Rwanda called Georges Mortehan

introduced a reform in the administrative structure of Rwanda. This reform

was essentially aimed at new distribution of powers. Therefore, Rwanda

which was originally governed under 20 districts (ibiti) and pastoral fiefs

(ibikingi) was transformed into a system of territories,

chiefdoms and subchiefdoms. By 1931, Rwanda consisted of 10 territories

instead of 20 districts, 52

chiefdoms (chefferies) corresponding more or less to historical traditional

regions and 544 sub-chiefdoms (sous- chefferies) equivalent to former

pastoral fiefs. The functions of the land chief (umutware w’ubutaka), the

cattle chief (umutware w’umukenke) and the military chief (umutware

w’ingabo) were abolished. Chiefs now resided in their administrative placesand not at the royal court as it was before.

Unfortunately, the administrative responsibilities in the new structure

were unfairly done. It excluded the Hutu, Twa and Tutsi with a moderate

background in favour of the Tutsi from well to do families. The chiefs were

in turn replaced by their sons who completed from the school reserved for

sons of chiefs. This is because they were seen as being able to rule in amodern way.

In addition, with the Mortehan reform the traditional chiefs lost their power

because they now accomplished their duties under pressure of being

dismissed when they performed poorly. They became pure and simple

agents of the Belgian colonial administration. They no longer representedthe King or their subjects.

1.2. Deposition of King Yuhi V Musinga in 1931.

At the beginning of the colonial rule, King Musinga collaborated with the

German administrators and in return they helped him defeat the northern

rebellions. However, the relationships between the King Musinga and

the Catholic missionaries were not good because King Musinga was

accused of being opposed to the missionary activities. This situation

worsened with the coming of the Belgians who collaborated with theCatholic Church’s authorities.

In 1931, the report of the Vice Governor General Voisin accused King

Musinga of being opposed to moral, social and economic activities of the

colonial administration. The King was at the same time accused of being

hostile to the work of the Catholic missionaries. These attitudes brought

conflicts between the King and the colonial administration, the catholic

missionaries as well as Rwandan collaborators spearheaded by Kayondo,his brother-in-law.

These were the reasons which, after a lot of hesitation, forced the Belgians

to take the decision to overthrow King Musinga and replace him with his

son RUDAHIGWA who was then the chief of Nduga-Marangara. On 12th

November 1931, Governor General Voisin announced the deposition of

King Yuhi V Musinga. The king was asked to leave Nyanza royal court to

Kamembe in Kinyaga. Musinga left for Kamembe on 14th November 1931.

On that very date, Rudahigwa, the son of the chief of Nduga-Marangara,

was proclaimed King by Vice-Governor General Voisin under the royalname of Mutara III.

King Musinga was moved from Kamembe to Moba in Democratic Republic

of Congo (D.R.C.) in 1940. He spent the last bitter years of his life here,eventually dying on October 25th, 1944.

2. Socio-cultural reforms.

a) Education.

With the coming of the colonialists, itorero and other forms of traditional

education in Rwanda were abolished. They were replaced with secular

and religious education under the control of the missionaries. The most

important skills acquired from these formal schools were reading, writing

and arithmetic. This new form of education also enabled learners to

acquire skills necessary to work for Belgians. Unfortunately, this did not

benefit the local populace, especially the younger generation, which losttouch with their history and ancestry.

Contrary from what was expected, the shift from traditional education to

the modern education did not serve to address national needs at that time.

It instead provided avenues of climbing to a higher social status. Those who

went through formal education came to be perceived as being of a better

status than those who did not have this type of education. This divided thesociety rather than unite it as traditional education had done.

This type of education introduced was a monopoly of Christian

missionaries and the main courses taught at the begining were religion,

arithmetic, reading and writing (Kiswahili, Germany and later French withthe Belgians). Then after, programmes have been improved.

In 1925, the colonial administration had committed itself to financing

education under certain conditions (subsidized education system):

acceptance of administrative inspection and employing qualified teachers.

From that time, primary education which was limited to a lower level was

expanded. For instance, in 1925, the number of pupils was 20,000, in 1935

was 88, 000 pupils and in 1945 the number had risen to 100, 000 pupils in

primary schools. Secondary schools started in 1912 with the creation of the

minor seminary of Kansi which in 1913 was shifted to Kabgayi. In 1929, with

the establishment of the Groupe Scolaire d’Astrida, secondary educationgrew and increased.

In 1933, the pupils of the former school for the sons of chiefs who lived at

Nyanza were enrolled. Apart from Groupe Scolaire d’Astrida, there were

other secondary schools which include the following:

Teacher Training School in Save which was started and managed

by the Marist Brothers.

Teacher Training School in Zaza by Brothers of Charity.

Teacher Training School in Ruhengeri by Brothers of Christian

Instruction.

Teacher Training School for girls at Save managed by White Sisters.

Teacher Training School in Kigali for girls ran by the Benedictine

Sisters while their auxiliary laymen ran other Training College at

Muramba and Byimana.

Teacher Training School College in Shyogwe by the Alliance ofProtestants

b) Introduction of identity cards

Before the colonial form of identification, a Rwandan was first identified by

his clan. Being Hutu, Twa or Tutsi was a mere social category. The identity

cards which were introduced by the Belgians in 1935 classified Rwandans

as belonging to Tutsi, Hutu and Twa. Each Rwandan had an ethnic identity

card in the years that followed later. To ascertain where one belonged,

those who owned ten cows or more were classified as being Tutsi. Those

with less cows were classified as Hutu while Batwa were considered thoseRwandan who survived on pottery activities.

Unfortunately, there were cases where some of the children belonging to

the same parent could be classified both as Hutu and Tutsi. For instance,

one who had cows was regarded as a Tutsi and another one without cowswas regarded as Hutu, yet the two shared same biological parents.

c) Health centres.

Before the coming of colonialists in Rwanda, Rwandans used natural

herbs (imiti gakondo) to cure various diseases such as malaria and

headaches. However, colonialists phased out of local herbs and replaced

them with western drugs and medicines. In collaboration with the Christian

missionaries, the health sector was transformed by constructing various

hospitals in different parts of the country. The medical sector was left in the

hands of the Christian Missions. By 1932, the colonial administration had 2hospitals including Kigali hospital and Astrida as well as 29 dispensaries.

From 1933, the colonial administration introduced a new policy of replacing

all dispensaries with mobile “assistance camps”. All this is aimed at

providing health care to the local populace in order to solve the problem of

insufficient medical infrastructure. The private hospitals were put in place

in Kigeme and Shyira by the Anglican Church and some others by Mining

companies like hospital of Rutongo by SOMUKI and Rwinkwavu Hospital

by GEORWANDA. Other hospitals set up by Christian Missionaries in

different parts of the country among others included the following set upthe following:

• Kabgayi and Mibilizi by the Catholic missionariesIn an attempt to increase the medical staff, a section of training of medical

• Kilinda by the Presbyterians

• Gahini by the Anglicans• Ngoma-Mugonero by the Adventists.

assistants was opened in Groupe Scolaire of Astrida and medical auxiliaries

also opened at Astrida and 2 schools for Assistant Nurses at Kabgayi and

in Kigali. As a result, by the end of Belgium mandate, 4 rural hospitals andmore than 10 dispensaries had been built by the colonial administration.

d) Religion (Christianity).

Before the coming of the colonialists, the king was not only the head

of the monarchy, but also a spiritual leader. He was considered divine

and therefore held religious rituals regularly. He was thought to be a link

between his people and the ancestors. Colonial agents worked against

traditional religion as they considered it pagan and backward. In fact,they considered the African way of life to be that of uncivilised people.

They used this as an excuse to introduce and support Christianity overtraditional religion.

Important to note is that the spread of Christianity and Christian culture

benefited a lot from the 1926 colonial administrative reforms. These

reforms required that to be a chief or sub-chief, one was to have at least

some western education acquired from the colonial schools in Rwanda.

Catholicism was the most dominant religion among other denominations

like the Presbyterian, Anglican and Adventists. Churches were built across

the county in places such as Zaza, Nyundo, Rwaza, Kabgyayi, Kilinda,Gahini and Gitwe.

3. Economic reforms.

Rwanda experienced a lot of transformation during the Belgian Mandate.

Such had both negative and positive effects on Rwandans. Some of the

economic reforms introduced in Rwanda during the Belgian Mandate

include the following:

i) Forced labour policy.

During the Belgium rule, some members of a family were required to offer

free compulsory labour. This was to accomplish some projects started

by the colonial government in a system called the akazi. This labour to

the government was to be offered for two days in a week of seven days.

Worse still, the forced labour was given amidst cruelty and brutality from

the administrators. The introduction of akazi made people feel that theywere being punished.

The local people underwent suffering while constructing roads, churches

and hospitals. This included transporting construction materials from

different areas to Kabgayi Catholic Church and growing and cultivating

various crops like cassava, sweet potatoes and coffee far from their homes.

Locals were also required to transport European goods to places they

were asked to. Sometimes, people were obliged to travel long distance to

cultivate the food crops(shiku) such as cassava, sweet potatoes and cash

crops like coffee. These were cultivated a way from their homes, often

near the roads where colonial officials could usually pass so as to creategood impression.

Due to the forced labour policy, the locals could not get enough time to

work on their farms. They instead concentrated on working on coffee

farms, with little or no pay. This led to a shortage in food supply. As a result,

a number of famines were experienced, such as Rumanura (between 1917

and 1918), Gakwege (between 1928 and 1929) and Ruzagayura (between

1943 and 1944). These famines affected people more often than before the

coming of the colonialists. It too resulted into fleeing of many Rwandeseto neighbouring countries like Congo and Uganda to look for paid labour.

ii) Agriculture and animal husbandry.

The Belgians introduced cash crops such as coffee, pyrethrum, cotton and

tea. Unfortunately, this was done through forced labour where labourers

worked for long hours. They established agricultural research centres in

various parts of the country to ensure the best harvests. These included

Rubona (Southern Province), Rwerere (Western Pronvince), and Karama

(Eastern Province).The Rubona agriculture research station was to deal with agricultural

problems affecting average attitude land, Rwerere station in Gisenyi

dealt with those affecting higher attitude while Karama station was for low

attitude areas. Overemphasis on these crops meant that food crops were

not considered as important. The result was frequent food shortages and

famines. The Belgians countered food shortages by introducing cassava,

maize, soya beans and Irish potatoes to try to improve food production for

subsistence farmers. This was important especially because of the two

droughts and subsequent famines of Rwakayihura/Rwakayondo and

Ruzagayura between 1928-29 and 1943-44 respectively.

Hybrid cattle breeds were also introduced to boost the production of hides

and skins for export. To support animal husbandry, research centers were

set up at Nyamiyaga-Songa in the southern region, Cyeru in the northern

region and Nyagatare in the eastern region. Animal health centres were

built and veterinary clinics established in rural areas to improve the local

breeds by cross breeding them with exotic ones. This was to develop moreproductive and resistant breeds.

iii) Mining activities.

Mining activities started from 1923 with two main companies:

RwandaUrundi Tin Mines Company (MINETAIN: Société des Mines d’Etain du

Ruanda-Urundi) and Muhinga-Kigali Mining Company (SOMUKI: Société

Minière de Muhinga-Kigali) in1934. Some other mining companies such

as GEORWANDA were established in 1945 while Compagne de Recherche

et d’Exploitation Minière (COREM) was established in 1948. The major

minerals extracted by the mining companies were gold, cassiterite,

wolfram, tin, colombotantalite and mixed minerals. These mines not

only increased the volume of exports but also provided local people withemployment opportunities.

iv) Taxation policy.

In a bid to increase tax revenue to finance their administration and projects,

Belgians introduced poll tax in 1917. This was compulsory for all adult

male Rwandans. This was to be paid in form of money. Unfortunately,

the methods of collection were brutal. Tax defaulters were flogged while

others were imprisoned, which made many people who were unemployedto run to the Belgians to look for jobs so as to pay taxes.

v) Trade and commerce.

In pre-colonial times, Rwanda’s socio-economic activities revolved around

cattle rearing, crop cultivation, ironwork, art and crafts and hunting. These

activities provided the local population with products for subsistence

consumption. However, surplus products were used for trade with the

neighbouring communities. Like many countries in Africa, trade of goods

and services was carried out in Rwanda through a barter trade where goodswere exchanged for other goods.

During the colonial period, Congo, Rwanda and Burundi were placed

under common Belgian protectorate from 1916 to the early 1960s. The

introduction of head-tax and use of money as a medium of exchange

by the Germans and Belgians respectively changed the society’s socioeconomic

perception of wealth. Over time, trading centres started to

develop. People could find agricultural products as well as crafts fromsuch centres.

Colonial administrators established commercial centres where local and

foreign traders like Europeans and Asians could trade. Others who took part

in the trade were the Belgians, Portuguese, Indians, Greeks, the Omani’s

and Pakistanis who operated licensed businesses. Generally, the business

environment has been expanding since then, to include cross-border andinternational trade.

vi) Infrastructural development.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Belgians constructed roads to facilitate trade and

effectively administer the colony. The first vehicle arrived in Rwanda in 1927,

which led to the construction of the following three international roads:• Bujumbura-Bugarama-Astrida-Kigali-Rwamagana-GatsiboNyagatare- KagitumbaHowever, European administrators generally overlooked the abuses of the

• Bujumbura-Cyangugu-Bukavu

• Bukavu-Cyangugu-Astrida

officials who embezzled the taxes that were collected. They also oversaw

forced labour during the construction of roads, in various mining activities

and during the planting of coffee. There was also the setting up of hydroelectric

power stations to produce electricity. These stations were set up

as from late 1950’s to supply power to developing industries. Those that

were constructed include Mururu (on River Rusizi) and Ntaruka (betweenlakes Burera and Ruhondo).

3.1. Reforms introduced during the Trusteeship (1946-1962)

After World War II in 1945, the victorious nations created the United Nations

Organisation (UNO) which replaced the League of Nations. This is because

the League of Nations had failed to promote world peace. The principal

mission of the UNO was to maintain peace and security in the world. By

this time, Rwanda’s mandate regime was replaced by the trusteeshipregime, although they were all under the Belgian authority.

On 13th December 1946, the UNO and Belgium signed a Trusteeship

Agreement on Rwanda. On April 29th, 1946, the Belgian Parliament

approved it. The UNO’s mission was to help prepare Rwanda to reach

autonomy before its independence. Later on, the UNO began to visit

every two years. The purpose of these missions was to hold consultations,

examine together with the state holding trusteeship any petition arising

from the administrated population and to assess the political situation ofthe countries under the trusteeship. Such missions in Rwanda were in 1948,

1951, 1954, 1957 and 1960. The UNO requested Belgium to assist her colonies

for the political evolution. The trusteeship had the following general

objectives:• To maintain international peace and security.When UN mission visited Rwanda in 1948, they found that Belgians had

• To help in political, economic, social and cultural development

of the inhabitants of the territories under trusteeship.

• To ensure progress towards either autonomous leadership or

independence.

• To promote respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms

for all irrespective of the race, gender, language and religion.

• To ensure equal treatment in all social, economic and financial

problems to all the members of the UN.

done nothing to enable Rwanda to reach the political evolution expected.

The UN left after requesting Belgium to prepare Rwandans to reach

autonomy that was desired for political independence. Belgium, instead

of acting as requested by the UN, introduced the Ten-Year Plan. This

was aimed at achieving social and economic development than politicaldevelopment as requested by the UNO.

1. Economic reforms.

The first mission of the UNO in 1948 realised that the Belgian government

had not done much in socio-economic development and recommended

that more social and economic reforms be promoted. In reaction to this

recommendation, the Belgian government elaborated a Ten Year socialand economic development plan for Rwanda-Urundi in 1951.

i) The Ten-Year Development Plan.

The Belgian-led administration in Rwanda put in place a Ten-Year

Development Plan, which was meant to bring about political, economic

and social development in Rwanda. It also focused on providing significant

financial support in public health, agriculture and education. However,

this Plan had several weaknesses. These include:• It was projected over a long period of time.• Since the Belgian administrators who were in charge of the plan

• Not all the people of Rwanda were involved in its formulation. Only

the leaders were told about it while the rest of the population wasignored.

could be moved from one country to another, it was difficult for it to

be effectively implemented.

The Ten-Year Development Plan resulted to notable changes in Rwanda,

even if these changes were slow despite its full implementation. Under

this Plan, the following was achieved:

• There was an improved access to education, although most of the

learners continued to receive basic education. Numbers decreased

as learners continued to advance into higher classes.

• It had a range of strategies aimed at preventing famine.

• The increasing monetarisation of the Rwandan economy enabled

more people, apart from the elites, to realise the advantages and

opportunities associated with business activities.

• Access to medical care also became more equitable, widely available,

effective and affordable – independent of sub-group identity.

• Several projects were financed under this Plan, like the construction

of schools, hospitals, dispensaries, roads and the development of

marshlands and the plantation of forests. Financing of the Ten-Year

Plan was in two forms, that is:

• External financing, which the Belgians achieved by creating a ‘‘Fonds

du Bien-Etre Indigène’’ with two million francs. Belgium was also

committed to annual financial aid which increased from 150 million

per annum in 1950 – 1951 to 560 million in 1961.

• Financing local projects was done through increasing tax rates on cattle,

subjecting polygamy taxation as well as taxing exports.ii) Abolition of Ubuhake.

On land authorities, there were considerable socio-economic reforms

which were done. Among the most notable ones, there was the abolition

of the socio-economic dependence system based on the cow or ubuhake

by the royal decree of the King Mutara III Rudahigwa on 1st April 1954. The

abolition of ubuhake was as a result of the decision of the king in agreement

with the indigenous Rwandan Superior Council. The traditional patronclient

relationship of ubuhake was a highly personalised relationship

between two individuals of unequal social status. The king further argued

that the clientship was an obstacle to economic development that could

create disorder among the people if not stopped. This abolition had two

objectives:

• To liberate the pastoral clients (abagaragu) who used to spend much

of their time working for their patron (shebuja)

• To encourage private initiatives and to force cattle keepers to reducethe number of cows to manageable and profitable size.

2. Political reforms.

During the reign of the Belgian Trusteeship, there were two political

reforms brought by the Belgian administrators: the establishment andcreation of councils.

Establishment of councils.

The first reform of its kind was introduced on May 4th, 1947. It was the

creation of a Conseil du Governement du Ruanda-Urundi. The

Council comprised of 22 members, 5 of whom were Belgians including

the Governor, 2 Resident Representatives and 2 Belgian state agents. The

other 13 members were said to represent other foreigners living in RuandaUrundi.

From 1949, the Kings of Ruanda-Urundi became members of the

Conseil du Governement. This Council was majorly meant for consultation.

On March 26th, 1949, it was abolished by a Belgian royal decree andreplaced with the Conseil Général du Ruanda-Urundi.

Conseil Général du Ruanda-Urundi was composed of 50 members. 9 of these

were high level personalities and automatic members, who included the

Governor, 2 Residents, 2 kings and 4 high level Belgian functionaries.

Apart from these, there were seats reserved for 4 representatives chosen

by the Haut Conseil du Ruanda-Urundi from among its members, 18representatives of expatriates and 14 members appointed by the Governor.

Another political reform initiated by the Belgians in Rwanda was because

of the Decree of 14th July 1952. This was in response to the critical reports of

the United National Trusteeship missions in Rwanda in 1948 and 1951. The

decree led to the establishment of councils at local and country levels.

They included Conseil de sous-chefferie (sub-chief councils), Conseil de

chefferie (the council of chiefs), Conseil de territoire (the council of territory)and Conseil Superieur du Pays (the superior council of the country

The Councils established served for consultation purposes only. They did

not have any power in decision making. The composition of each councilwas as follows:

(a) Conseil de sous-chefferie (the Council of sub-chiefs): It was made

up of a sub-chief who presided over it and 5 to 9 elected members.

(b) Conseil de chefferie (the Council of chiefs): This was composed of

the chief himself who was its chairperson and 10 to 18 members

of whom 5 were sub-chiefs elected by their peers. Others were

notables elected from members of a college made up of 3 notablesfrom sub- chiefdoms.

(c) Conseil du territoire (the territorial council): This was made up of

the head of the territory and chiefs from that territory as well as

a number of sub-chiefs which had to be equal to the number of

chiefs. The sub- chiefs who sat on this council were chosen by their

fellow sub-chiefs from their ranks. There were also notables on the

council whose number was equal to that of chiefs and sub-chiefs.

The notables were elected from an electoral college composed

of 3 people elected by each conseil du territoire from among itsmembers

(d) Conseil Superieur du Pays (the high council of the state): This was

presided over by the king. It was made up of representatives of

the councils of the 9 territories (Cyangugu, Astrida, Nyanza, Kigali,

Kibungo, Byumba, Ruhengeri, Gisenyi and Kibuye), 6 chiefs elected

by their peers, a representative elected by each council of the

territory from the members who sat on it, 4 people chosen because

of their understanding of the problems of the country and 4 peoplechosen based on their level of assimilation towards western culture.

The councils were created mainly because the trusteeship terms provided

that the Belgian administration was to increase the participation of

Rwandans in the administration of their country. Thus, the powers of the

local government were increased although they were to be supervised

by the trusteeship administration. However, the elections to the councilswere to be indirect, and the chiefs were tasked to determine the outcome.

The decree also had the following effects:

• It empowered the king to make regulations in the administration of

the kingdom.

• The king was also authorised to make arrangements for social and

economic services and to impose communal labour in 60 days.

• The chiefs had authority to implement the decrees of the king

especially communal labour and labour services for the chiefs.The right to vote was introduced in 1954. Nevertheless, the system could

hardly be described as democratic. For example, notables responsible for

electing the sub-chiefdom councils – that is, the lowest level of councils

– would themselves now be elected rather than nominated. Each council

would thereafter vote on the membership of the superior council of the

country council as previously done. Very important to note was that only

nationals were allowed to be members of these councils and they served

for a period of three renewable years. The administrative structure ofRwanda after establishment of these councils by 1952 was as follows:

Suggestion: territorial administration could be under the UMWAMI, and eachcouncil would correspond or be on the same level as the administarive leader.

4. Decolonisation of Rwanda.

The Belgians applied the divide and rule system of administration. In

Rwanda, they took advantage of the historic division of labour between

the Hutu, Twa and Tutsi. They went ahead to incorporate the Tutsi into

the ruling class. Generally, the Belgian rule was characterised by social

favouritism towards the Tutsi. From the conseil supérieur du pays, amemorandum called Mise au point was made on 22nd February 1957.

This was mainly addressed to the UN Trusteeship mission to Rwanda and

to the Belgian colonial administration. This document strongly questioned

the colonial power. It criticised discrimination based on colour, questioned

monopoly of the missionary-led education which compromised its quality

and finally demanded for increased representation of Rwandans in thepolitical administration of their country.

More so, the Mise au point made the Belgian authorities to mobilise Hutu

intellectual group (former seminalists) to write another memorandum

as a counterattack which they called Le Manifeste des Bahutu (Hutu

manifesto) or note sur l’aspect social du problème racial indigène

au Rwanda. It was produced on 23rd March 1957. The signatories of this

memorandum included Grégoire Kayibanda, Joseph Habyarimana Gitera,

Calliope Murindahabi, Maximillian Niyonzima, Munyambonera Silvestre,

Ndahayo Claver, Sentama Godefroid and Sibomana Joseph among others.They were majorly opposed to a memorandum called Mise au point.

In such a situation, the colonial power had successfully created a HutuTutsi conflict,

which had never been there before. Later, it became a barrier

to the unity of Rwandans. This prompted King Mutara III Rudahigwa to

establish a committee to study the “Muhutu-Mututsi social problem” on

30th March 1958. In June 1958, the conseil supérieur du pays produced

a reaction on the report established by the committee. They pointed

out that there was no Hutu– Tutsi problem that existed but a socialpolitical

problem on the level of political administration. This problem,

they concluded that, was not ethnic in nature. The conseil supérieur du

pays members moved on to demand the removal of the ethnic mention

in the identity cards. The situation intensified with the creation of politicalparties in Rwanda competing for power. These political parties included:

• Union Nationale Rwandaise (UNAR).

The Union Nationale Rwandaise (UNAR), or Rwanda National Union Party,

was officially formed on 3rd September 1959. Its President was François

Rukeba. Its other leaders were Michel Rwagasana, Michel Kayihura, Pierre

Mungarurire and Chrisostome Rwangombwa among others. The party

was basically a nationalist, monarchist, anti-colonialist and reformist

party. It was formed to demand for immediate independence of Rwanda.

• Rassemblement Démocratique du Rwanda (RADER).

Rassemblement Démocratique du Rwanda (RADER) or Rwanda

Democratic Assembly, had the following members: Bwanakweli Prosper,

Ndazaro Lazarus, Priest Bushayija Stanslas and Etienne Rwigemera. This

Party was quite close to the colonial administration and the Catholic

Church. It was also democratic and advocated for constitutional monarchy.

Parti du Mouvement pour l’Emancipation Hutu

(PARMEHUTU).Parti du Mouvement pour l’Emancipation Hutu (Movement for the

Emancipation of the Hutu) was formed in October 1959. It was officially

launched as a Party on 18th October 1959 with Grégoire Kayibanda as

its President. Other prominent members were Niyonzima Maximillien,

Ndahayo Claver, Murindahabi Calliope, Makuza Anastase, Rwasibo Jean

Baptiste and Dominique Mbonyumutwa. In the beginning, it seemed to

advocate for constitutional monarchy. However, later on, it advocated for

a republican state. On May 8th, 1960, while in its meeting at Gitarama, the

abbreviation of MDR (Mouvement Démocratique Républicain) was adoptedto PARMEHUTU.

Association pour la Promotion Social de la Masse(APROSOMA).

APROSOMA stands for Association pour la Promotion Sociale

de la Masse (Association for Social Promotion of the Masses). It was

established on 1st November 1957 by Joseph Habyarimana Gitera. It

was launched officially as a political party on February 15th, 1959. Its

other influential members were Munyangaju Aloys, Gasigwa Germain

and Nizeyimana Isidore. The day-to-day activities of APROSOMA were

not far different from that of PARMEHUTU.

Besides the above national political parties, there existed other localpolitical clubs. Some of these were:

AREDETWA: This stands for Association pour le Relèvement Démocratique

de Batwa (Association for Democratic Elevation of Batwa). It was founded

by Laurent Munyankuge from Gitarama. This party was later absorbed

by PARMEHUTU.

APADEC: This stands for Association du Parti Démocratique

Chrétien (Association of Christian Democratic Party). Its founder was

called Augustin Rugiramasasu.

UMUR: This stands for Union des Masses Rwandaises.

UNINTERCOKI: This stands for Union des Intêréts Communs du Kinyaga.

ABAKI: This stands for for Alliance des Bakiga.

MEMOR: This stands for Mouvement Monarchiste Rwandais.

MUR: This stands for Mouvement pour l’Union Rwandaise.

The formation of these political parties led to severel public political

gatherings. These gatherings were followed by violence. It explains the

subsequent violence that occurred in the years that followed. From 1st to

7th November 1959, violence broke out in Gitarama against the Tutsi and

the members of UNAR. This was started by the members of PARMEHUTU

and APROSOMA from Byimana in Marangara. Soon, it spread to Ndiza,Gisenyi and Ruhengeri.

The origin of this violence was believed to be the attack of Dominique

Mbonyumutwa, a member of PARMEHUTU, (who was the chief of

Ndiza at that time). He was attacked by young UNAR members as he

was leaving Catholic Church service on November 1st, 1959 (All Saints Day)

at Byimana Parish, in the former prefecture of Gitarama in the present

day Ruhango District. Between 7thand 10th November 1959, there was

a counterattack prepared by the members of UNAR against the major

leaders of PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA. These attacks had beenhindered due to intervention of the Force Publique.

During that period, the resident representative Preud’homme had put

Rwanda under a military occupation regime. Colonel Guy Logiest was

dispatched from Stanleyville (Kisangani in Belgian Congo) and appointed

commander of the military forces which were operating in Rwanda at thetime on the 11th, November 1959.

This violence had various effects, which included:a) Houses belonging to the Hutu and Tutsi were destroyed systematically.

b) Many Tutsi were killed, internally displaced and became refugees

in neighbouring countries like in Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania and

Belgian Congo.

c) There were arbitrary arrests, imprisonments and assassinations.

d) The twenty chiefs were dismissed, and 150 sub-chiefs replaced by

the The General Governor changed the title and became General

Resident

e) The sectors or sub-chiefdoms were reduced from 544 to 229. They

were renamed Communes headed by Bourgmestres thencommunal

elections were prepared.

f) The 10 Territoires become Prefectures headed by the Préfets whowere appointed.

g) The High Councils of the state was dissolved and replaced by a

Special Provisional Council comprising 8 members from 4 political

Parties namely RADER, PARMEHUTU, UNAR and APROSOMA. This

Special Provisional Council was formed on 4th February 1960 at

Kigali. King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa could not hide his hostility forthat council because it actually substituted his powers.

h) The chiefdoms or Districts were abolished.

From 26th to 30th July 1960, there were communal elections. The

following results were realised: PARMEHUTU obtained 70.4% equivalent

to 2,390 Communal Councilors, APROSOMA obtained 7.4% equivalent

to 233 Communal Councilors, RADER obtained 6.6% equivalent to 206

Communal Councilors and UNAR got 1.8% which was equivalent to 56

Communal Councilors. From these elections, PARMEHUTU got 166

Bourgmasters from which 21 were from APROSOMA, 18 from APROSOMAPARMEHUTU,

7 from RADER and 17 from different political parties.

In reference to these results, PARMEHUTU was declared the winner. In

the meantime, UNAR protested against these results and so did King

Kigeli V Ndahindurwa. For this reason, King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa on July

1960 was forced to go to Congo Belgian to meet the UN Secretary General

and as well as to attend Congo’s independence celebration. After these

elections, the Belgian Minister in charge of Ruanda-Urundi issued ordersstopping King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa from returning to Rwanda.

.This made the Resident General put in place a Provisional Government on

.This made the Resident General put in place a Provisional Government on

26th October 1960. This was made up of 10 Rwanda Ministers and 9 Belgian

State Secretaries. A few months later, on 28th January 1961, there a coup

at Gitarama, famously known as Coup d’Etat de Gitarama. During this time,

a meeting took place in a marketplace in Gitarama in which about 2,900

Councilors and Bourgmestres who had been elected from PARMEHUTU

and APROSOMA political parties participated.With full support of the Belgian government, the following resolutions

were reached:

• The monarchy was abolished.• The Kingdom emblem and the royal drum (Kalinga) was also abolished.

The Ubwiru institution was also abolished.

• Rwanda was officially declared a Republic.

• Mbonyumutwa Dominique was elected as the first President of the

Republic.

• There was the formation of a government made up of 11 ministers

with Grégoire Kayibanda as Prime Minister.

• There was to be a constitution and a judiciary based on the newstate.

In February 1961, the Belgian Trusteeship confirmed that regime and

transferred the power of autonomy to them. A new tri-colour flag of Red,

yellow and Green was exhibited on 26th February 1961. On September

25th, 1961, legislative elections and a referendum were organised and were

won by PARMEHUTU.It was declared that many voters voted ‘‘No’’ against

the monarchy and the candidature of King Kigeli V Ndahindurwa.On 2nd October 1961, the legislative assembly was put in place. Grégoire

Kayibanda was elected the President of the Republic by the Legislative

Assembly headed by Joseph Habyarimana Gitera. On 1st July 1962, Rwanda

recovered its independence, and the Belgian flag was replaced by the

Rwandan flag. On 31st December 2001 a new Rwandan flag was launched.

Application Activity 8.31. Discuss the objectives of abolition of Ubuhake by King Mutara8.4. Effects of Belgian colonization in Rwanda

Application Activity 8.31. Discuss the objectives of abolition of Ubuhake by King Mutara8.4. Effects of Belgian colonization in Rwanda

III Rudahigwa

2. Describe the colonial exploitation mechanisms Present thefindings in class.

Assess the reforms made by Belgian colonial administrators between

Learning Activity 8.4.

Learning Activity 8.4.1916-1962. Thereafter, make a presentation in class

1. Political effects.a) Change in the traditional administration