UNIT 12 GENDER BASED VIOLANCE (GBV)

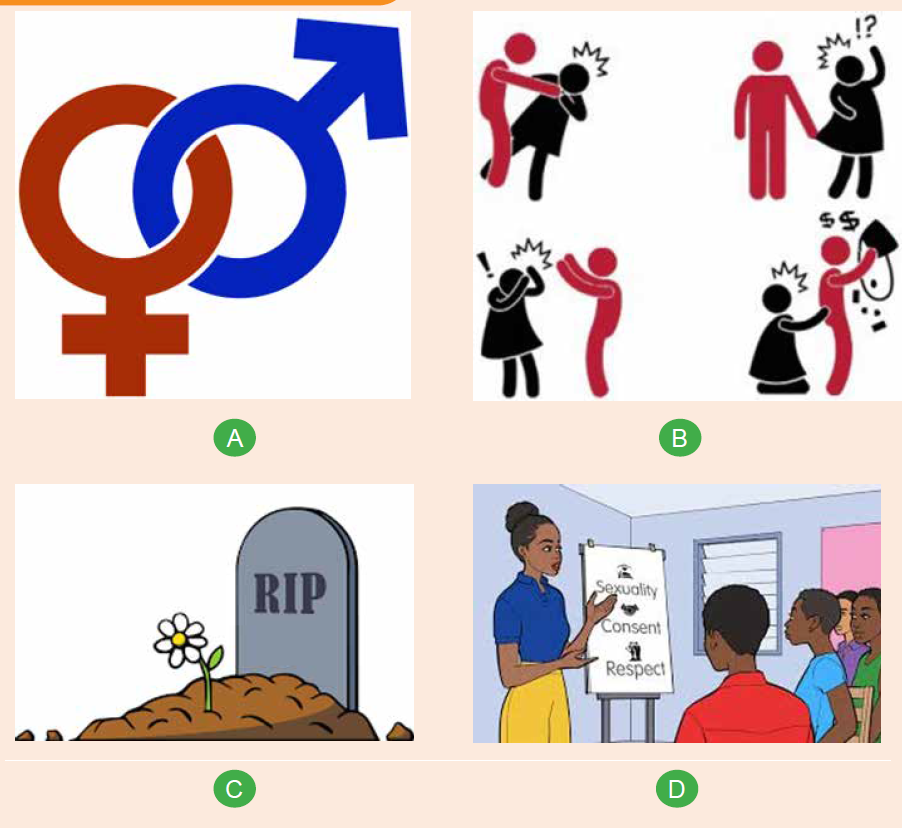

Introductory activity 12

Observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What do you think Image A represent?

b. What do you think picture B is trying to describe?

c. What do you think image C?d. What do you think is happening in image D?

12.1.Introduction to gender and gender-based violence

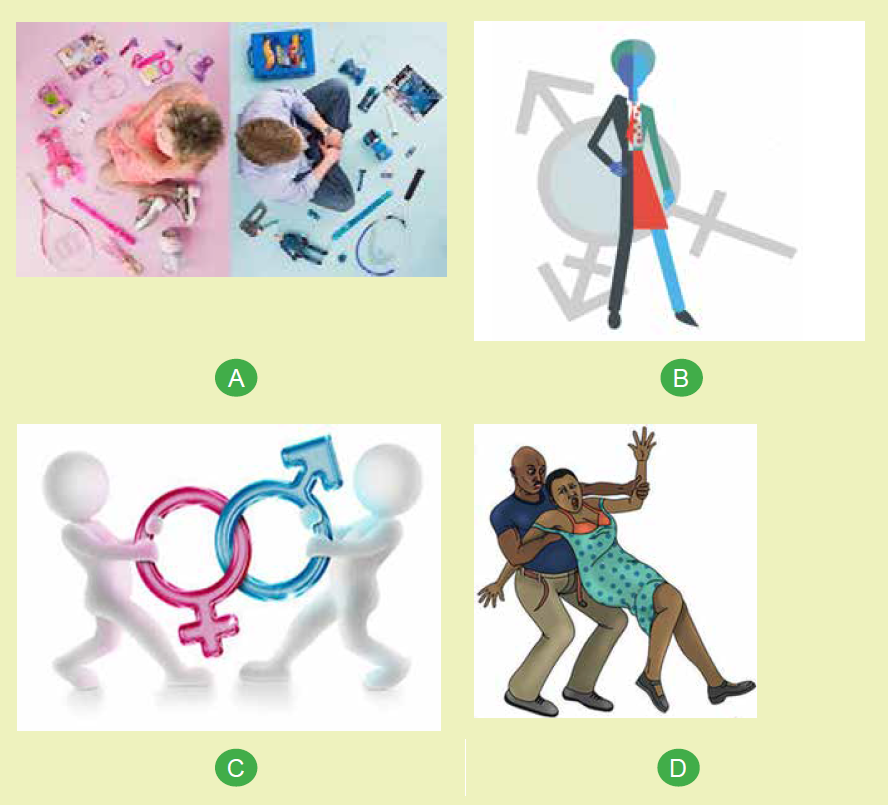

related conceptsLearning activity 12.1

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What does image A try to explain?

b. What do you think of image B?

c. What do you think of image C is about?d. What do you think is happening in image D?

12.1.1 Gender and sex

Gender refers to what it means to be a male or a female in a given society and

culture. Thus, gender is social construct that determines the roles, behaviour,

activities and attributes that a particular society at a given time considers appropriate

for men and women, girls and boys. It is shaped by the sociocultural environment

and experience in addition to biology and vary widely within and between cultures

and often evolve over time.

Gender is not synonymous to sex; which refers to biological classification of

people as male or female based on physical and physiological features including

chromosomes, gene expression, hormone level and function, and reproductive and

sexual anatomy. The term “intersex” is used as an umbrella term for individuals

born with natural variations in biological or physiological characteristics (including

sexual anatomy, reproductive organs and or chromosomal patterns that do not fit

traditional definitions of male or female. Infants are generally assigned the sex of

male or female at birth based on the appearance of their external genitalia.

12.1.2 Sexual orientation and gender identity

There is tremendous variability in the ways that individuals express their gender and

in the ways, they express their sexual orientation. Accordingly, various concepts exist

to accommodate these variations and healthcare providers should be conversant

with them to appropriately use them when working with diverse clients.

Sexual orientation is a function of sexual attraction, identity, and behavior. Sexual

attraction is about the type of person an individual desire sexually, romantically,

emotionally, and in other sexual ways; heterosexual individuals are attracted to

people of the opposite sex, homosexual individuals are attracted to people of the

same sex, and bisexual individuals are attracted to both people of the opposite

sex and the same sex. Sexual identity is about how people present their sexuality

to others, with some people very private about their sexual identity and others very

open. Sexual behavior is about the sexual actions in which a person engages.

Some people choose to be celibate.

Besides sexual orientation exists gender identity, which is an individual’s sense

of maleness or femaleness and gender expression which is how an individual

expresses their own gender to the world, i.e., through names, clothes, how they

walk, speak, communicate, their roles in society and general behaviour. These may

sometimes not match societally accepted norms for their biological sex at birth. A

cisgender person has a gender identity that aligns with the sex assigned to that

person at birth. A transgender person has a gender identity that does not match

the sex assigned at birth.

12.1.3 Gender equality and equity

Gender being an array of socially constructed characteristics and roles, makes it

hierarchical and is surrounded with inequalities and inequities. Gender inequality

refers to unequal treatment or perceptions of individuals based on their gender.

It emerges when one of the two sexes is considered more valuable, capable,

powerful, and has more access to information, resources and opportunities than

the other and is an important factor for gender-based violence. Opposed to this,

is gender equality that refers to a state where there is no discrimination on the

basis of a person’s sex in the allocation of resources and in the access to various

services in a society. With gender equality, individual’s rights, responsibilities and

opportunities are not determined by the sex they are assigned at birth nor gender

identity or sexual orientation.

To achieve gender equality, some strategies and processes “equity” come in.

Gender equity therefore refers to fairness and justice in the distribution of

resources, opportunities, and benefits to women/girls in relation to men/boys. It

implies objectivity of treatment for all genders with regards to their respective needs

and strives to bring all the genders to an equal playing field. It recognizes that certain

groups face disadvantages because of historical and structural reasons therefore

contextual measures required to ensure that their disadvantaging situations are not

perpetuated.

12.1.4 Gender-based violence

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to any act of violence that results in, or is

likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to someone

on the basis of their gender or sex. Although, this definition is applicable to both

men and women, the phenomenon of GBV mostly affects women. It roots deeply

in discriminatory cultural beliefs and attitudes that perpetuate inequality andpowerlessness, in particular of women and girls.

Self-assessment 12.1

1. What is the difference between gender and sex?

2. What does intersex mean to you?

3. Define the following concepts:

a. Gender-based violence

b. Sexual behaviourc. Gender identity

12.2 Role of gender in health promotion and diseases

preventionLearning activity 12.2

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What do you think image A is attempting to explain?

b. What do you think image A is attempting to explain?

c. Through the lens gender and health, attempt to establish a relationship

between image A and B

It is usually wise to spent little on health promotion and disease prevention

interventions than to spend relatively large amounts of money for recovery from

serious health problems. Disease prevention involves determining preventive

health interventions that are effective in various population group as well as how

well successful interventions can be scaled up for widespread implementation.

Health promotion, on the other hand, encourages individuals and communities

to improve their health through healthy public policies, supportive environments,

skilled personnel, strong communities, and increased access to preventive health

services.

Biological differences between male and female along with socially constructed

masculine and feminine the roles and responsibilities affect both health promotion

and disease prevention strategies. Cognizant of this, any of these interventions

should carter for these differences to yield good results. For instance, these

differences affect the way different individual or groups of individuals take risk

beside risks they are exposed to; their attempts to improve their health, and how

the health system responds to their needs. Furthermore, gender-based principles

as well as discriminatory societal and cultural norms and prejudices, may translate

into activities that harm one’s health and well-being.

12.2.1 Gender and health promotion

Gender influences on health include access to health-promoting resources,

commonplace exposure to health-damaging and health-promoting factors, and

varied expectations of behavior such as consuming alcohol, taking risks, and using

healthcare. For instance men have more harmful smoking practices, unhealthier

dietary patterns, heavier alcoholic drinking habits and higher rates of injuries and

interpersonal violence than women. With traditional masculinities and femininities

expectations women are less likely to engage into physical activities than men.

Additionally, traditional masculinities frequently function as a barrier to men

seeking health treatment, engaging in preventive behaviors, and managing selfcare,

whereas women’s health is frequently relegated to sexual, reproductive, and

maternal health.

Effective health promotion program should be holistic and use gender analysis

and gender integration for healthy public policies can be developed for concrete

and effective individual and community actions relevant to promoting health and

wellness. Effective health promotion policies and programmes are those centred on

joint commitment and that use a multi-sectorial approach and which are based on

evidence gathered with gender dimensions in mind.

12.2.2 Gender and diseases prevention

Gender norms, roles and relations influence the development and course of risk

factors of various diseases and impact the way men and women use services and

respond to healthcare services therefore affect various level of disease prevention.

For instance, traditional masculinities will often act as a barrier to men seeking

health care including those required for primary (e.g., vaccination), secondary (e.g.

checking blood pressure routinely to detect the onset of hypertension) and tertiary

(e.g. Physical therapy to people who have been injured in a vehicle collision in

order to prevent long term disability) disease prevention. Furthermore, they may

also adopt risky behaviours heavy smoking, drug use, etc. which is associated

disastrous health affects couple with poor self-care management.

On the other hand, women play a vital role in health promotion as in most culture

and societies they are regarded to master the art of taking care of others. For

instance their involvement into children vaccination program cannot be overlooked

beside the role they play in nutrition of their family members. Additionally, health

education messages quite often target women as viewed as care guarantor of every

individual in the household. Nevertheless, following prevailing gender inequalities

that affect mostly women, implementation prevention strategies might face short

comings, thus not as effective. These inequalities also expose women to GBV with

associated health outcomes hence specific prevention strategies.

As for health promotion, disease prevention plans should address differences

between women and men, boys and girls in an equitable manner in order to beeffective.

Self-assessment 12.2

1. Contrast health promotion and disease prevention

2. What should be done gender-wise, for an effective health promotionprogram?

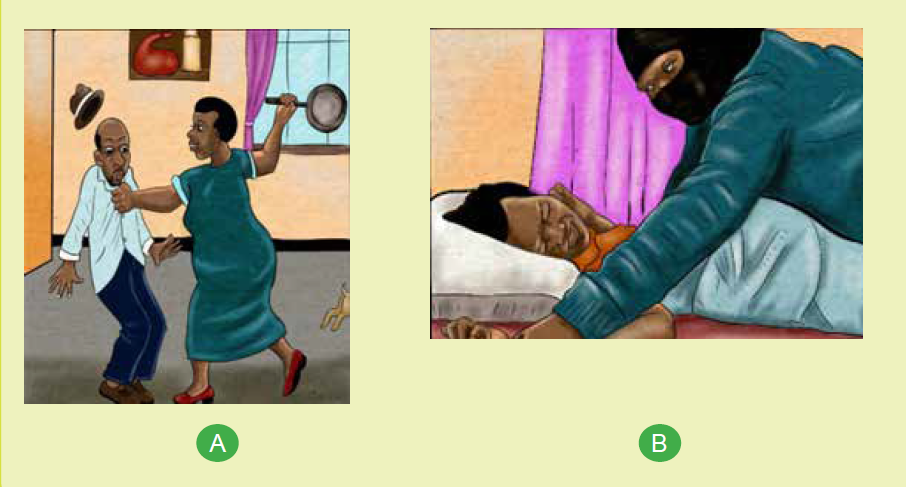

12.3. Types of gender based violenceLearning activity 1.8

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What is common across the above images?b. Describe what you see in each picture and attempt categorizing GBV

GBV is a complex phenomenon that affects both males and females differently,

women and girls being the most affected. Categorizing its different types varies;

and it can be categorized as Sexual violence i.e. rape, forced prostitution, incest,

sexual abuse, etc.; Physical violence i.e. trafficking, slavery, war, displacement etc.;

Emotional &psychological violence (abuse, humiliation, confinement, etc.);Harmful

traditional practices such as female genital mutilation, early marriage, honour

killing, etc.; and Socio-economic violence such as discrimination, social exclusion,

ostracism based on sexual orientation, etc.

a. Physical violence:

Physical violence is an act attempting to cause, or resulting in pain and or physical

injury through coercion. Physical violence in intimate relationships, often referred

to us as domestic violence, continues to be a widespread phenomenon in every

country. Acts of physical violence include beating, burning, kicking, punching, biting,

maiming or killing, or the use of objects or weapons.

Some classifications also include human trafficking and slavery in the category

of physical violence because initial coercion is often experienced, and the people

involved often end up becoming victims of further violence as a result of their

enslavement. Physical violence in the private sphere also affects young people. As

mentioned above, witnessing the abuse of one parent by another leads to serious

psychological harm in children. Often, children and young people who are present

during an act of a parent abuse like spouse abuse may also be injured, sometimes

by accident and sometimes because they try to intervene.

b. Verbal violence and hate speech

Verbal violence can include issues that are specific to a person, such as putdowns

(in private or in front of others), ridiculing, the use of swear-words that are

especially uncomfortable for the other, saying bad things about the other’s loved

ones, threatening with other forms of violence, either against the victim or against

somebody dear to them. At other times, the verbal abuse may be relevant to the

background of the victim, such as their religion, culture, language, (perceived)

sexual orientation or traditions. Depending on the most emotionally sensitive areas

of the victim, abusers often consciously target these issues in a way that is painful,

humiliating and threatening to the victim.

Most of the verbal violence that women experience because of being women is

sexualized, and counts as sexual violence. Verbal gender-based violence in the

public sphere is also largely related to gender roles and it may include comments

and jokes about women or may present women as sex objects (e.g. jokes about

sexual availability, prostitution, rape). A great deal of bullying is related to the

perceived sexuality of young people (especially boys).

The regular negative use of words such as “queer” or “fag” is often traumatizing for

those perceived as gays and lesbians. This is very likely one of the reasons why

many gays and lesbians only “come out” after secondary school.

Verbal violence may be classified as hate speech and can take many forms i.e.

words, videos, memes, or pictures that are posted on social networks, or it may

carry a violent message threatening a person or a group of people because of

certain characteristics.

Many cultures have sayings or expressions to the effect that words are harmless,

and there is a long tradition that teaches people to ignore verbal attacks. However,

when these attacks become regular and systematic and purposefully target

someone’s sensitive spots, the object of the attacks is right to consider themselves

victims of verbal abuse. Gender-based hate speech mainly targets women (in this

case, it is often called “sexist hate speech”).

Gender-based hate speech can take many different forms i.e. jokes, spreading

rumors, either using internet using online messaging, threats, slander, and

incitement of violence or hate. It aims at humiliating, dehumanizing and making a

person or group of people scared. As with any type of violence, gender-based hate

speech is usually very destructive for the person targeted. People who experience

hate speech often feel helpless, and do not know what to do.

c. Emotional & psychological violence:

All forms of violence have a psychological aspect, since the main aim of being

violent or abusive is to hurt the integrity and dignity of another person. Apart from

this, there are certain forms of violence which take place using methods which

cannot be placed in other categories, and which therefore can be said to achieve

psychological violence in a “pure” form. This includes isolation or confinement,

withholding information, disinformation, and threatening behavior. In the private

sphere, psychological violence includes threatening conduct which lacks physical

violence or verbal elements, for example, actions that refer to former acts of

violence, or purposeful ignorance and neglect of another person.

d. Sexual violence:

Includes actual, attempted or threatened (vaginal, anal or oral) rape, including

marital rape; sexual abuse and exploitation; forced prostitution; transactional or

survival sex; and sexual harassment, intimidation and humiliation. Furthermore,

sexual violence comprises engaging in non-consensual vaginal, anal or oral

penetration with another person, by the use of any body part or object; engaging in

other non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with a person; or causing someone

else to engage in non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with a third person. Marital

rape and attempted rape constitute sexual violence.

Examples of forced sexual activities include being forced to watch somebody

masturbate, forcing somebody to masturbate in front of others, forced unsafe sex,

sexual harassment, and abuse related to reproduction (e.g. forced pregnancy,

forced abortion, forced sterilization, female genital mutilation).

Certain forms of sexual violence are related to a victim’s personal limits, and are

more typical of the private sphere. The perpetrator deliberately violates these

limits: examples include date rape, forcing certain types of sexual activities. One

common example of such violence in the public sphere includes the isolation of

young women or men who do not act according to traditional gender roles. Isolation

in the public sphere is most often used by peer groups, but responsible adults such

as teachers and sports coaches can also be perpetrators. Most typically, isolation

means exclusion from certain group activities. It can also include intimidation, in a

similar fashion to psychological abuse in the private sphere withdrawal of sexual

attention as a form of punishment, or forcing other(s) to watch (and sometimes to

imitate) pornography.

e. Socio-economic violence

Socio-economic deprivation can make a victim more vulnerable to other forms of

violence and can even be the reason why other forms of violence are inflicted.

Typical forms of socio-economic violence include taking away the earnings of the

victim, not allowing them to have a separate income (giving them “housewife”

status, or making them work in a family business without a salary), or making the

victim unfit for work through targeted physical abuse.

Socio-economic violence in the public sphere is both a cause and an effect of

dominant gender power relations in societies. It may include denial of access to

education or(equally) paid work (mainly to women), denial of access to services,

exclusion from certain jobs, denial of pleasure and the enjoyment of civil, cultural,

social and political rights. Some public forms of socio economic gender-based

violence contribute to women becoming economically dependent on their partner

(lower wages, very low or no child-care benefits, or benefits being tied to the income

tax of the wage-earning male partner). Such a relation of dependency then offers

someone with a tendency to be abusive in their relationships the chance to act

without fear of losing their partner.

f. Domestic violence or violence in intimate relationships

Domestic violence includes acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic

violence that occur within the family or domestic unit or between former or current

spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same

residence with the victim. Domestic violence, or intimate partnership violence, is

the most common type of GBV. It also requires special attention, because it is

a relational type of violence, and the dynamics are therefore very different from

violent incidents that occur among strangers.

The fact that domestic violence was long considered to be a private, domestic

issue has significantly hampered recognition of the phenomenon as a human rights

violation. The invisibility of the phenomenon was reinforced by an understanding

of international human rights law as applicable only to relations between individual

and the state (or states). However, it is now recognized that state responsibility

under international law can arise not only from state action, but also from state

inaction, where a state fails to protect citizens against violence or abuse (the “due

diligence” principle).

Although the vast majority of domestic violence is perpetrated against women by

men, it actually occurs in same sex relationships just as frequently as in heterosexual

relationships, and there are cases of women abusing their male partners. Domestic

violence such as rape, battering, sexual or psychological abuse leads to severe

physical and mental suffering, injuries, and often death.

g. Harmful traditional practices and sexual harassment

Include female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C); forced marriage; child marriage;

honour or dowry killings or maiming; infanticide, sex-selective abortion practices;

sex-selective neglect and abuse; and denial of education and economic opportunities

for women and girls.

Sexual harassment defined as any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical

conduct of a sexual nature with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a

person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or

offensive environment. Verbal examples of sexual harassment may include making

sexual comments about a person’s body, making sexual comments or innuendos,

asking about sexual fantasies, preferences, or history, asking personal questions

about someone’s social or sex life, making sexual comments about a person’s

clothing, anatomy, or looks, repeatedly trying to date a person who is not interested,

telling lies or spreading rumors about a person’s sex life or sexual preferences.

Examples of non-verbal harassment include looking a person up and down

“elevator eyes”, following or stalking someone, using sexually suggestive visuals,

making sexual gestures with the hands or through body movements, using facialexpressions such as winking, throwing kisses, or licking lips.

Self-assessment 12.3

1. Explain the different types of gender-based violence?

2. Which of the following types of violence can be defined as a form of

psychological violence? (Choose all that apply):

a. Making threats

b. Teasing

c. Intimidation

d. Insulting someone and Bullying

e. Humiliation and Ignoringf. All of the above

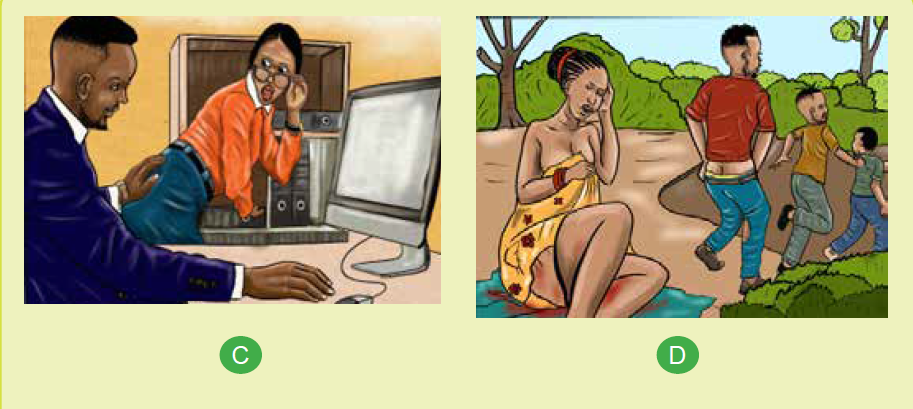

12.4. Common causes of Gender Based ViolenceLearning activity 12.4

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. According to your understanding, what each of the above image represents?

b. Referring to what you see on the above images, what do you think are

causes of the GBV?

The root cause of GBV is the imbalance of power in relationships between men and

women.

GBV is deeply rooted in discriminatory cultural beliefs and attitudes that perpetuate

inequality and powerlessness, in particular of women and girls. Various other factors,

such as poverty, lack of education and livelihood opportunities, and impunity for

crime and abuse, also tend to contribute to and reinforce a culture of violence and

discrimination based on gender.

However, a variety of factors on the individual level, the family level, and at the

level of community and society, often combine to raise the likelihood of violence

occurring. There is no single factor that can explain gender-based violence in our

societies, but rather a myriad of factors contributes to it, and the interplay of these

factors lies at the root of the problem. Cultural, legal, economic and political factors

are the main 4 categories of GBV underlying factors.

a. Cultural factors

These include gender stereotypes and prejudice, normative expectations of

femininity and masculinity, the socialization of gender, an understanding of the

family sphere as private and under male authority, and a general acceptance of

violence as part of the public sphere (e.g. street sexual harassment of women), and

or as an acceptable means to solve conflict and assert oneself.

Religious and historical traditions have sanctioned the physical punishment of

women under the notion of entitlement and ownership of women. The concept of

ownership, in turn, legitimizes control over women’s sexuality, which, according to

many legal codes, has been deemed essential to ensure patrilineal inheritance.

Sexuality is also tied to the concept of so-called “family honour” in many societies.

With this regards, traditional norms in these societies allow the killing of women

suspected of defiling the “honour” of the family by indulging in forbidden sex or

marrying and divorcing without the consent of the family. The same norms around

sexuality can help to account for the mass rape of women.

b. Legal factors

Being a victim of GVB is perceived in many societies as shameful and weak, with

many women still being considered guilty of attracting violence against themselves

through their behaviour. This partly accounts for enduring low levels of reporting and

investigation. Until recently, the law in some countries still differentiated between

the public and private spaces, which left women particularly vulnerable to domestic

violence.

There are times even though most forms GVB are criminalized, the practices of law

enforcement may in many cases favor the perpetrators, which help to account for

low levels of trust in public authorities and for the fact that most of these crimes go

unreported. In many societies, the decriminalization of homosexuality is still relatively

new. While some countries have made progress by allowing equal marriage, this

has often resulted in a backlash, such as strengthening opinions that the traditional

family is a union between a man and a woman, or where governments have passed

laws prohibiting “gay propaganda.”

c. Economic factors

Scarcity of resources generally makes women more vulnerable to violence and

sometimes men as well. It creates patterns of violence and poverty that become

self-perpetuating, making it extremely difficult for the victims to extricate themselves.

When men face unemployment and hardship, they may react violently to assert

their masculinity.

d. Political factors

The under-representation of women in power and politics means that they have

fewer opportunities to shape the discussion and to affect changes in policy, or

to adopt measures to combat GBV and support equality. The topic of genderbased

violence is in some cases is deemed not to be important, with domestic

violence being given insufficient resources and attention. Though, women have

raised questions and increased public awareness around traditional gender norms,

highlighting aspects of inequality and its relationship to GBV, this status quo has not

changed much due to lack of enough political influence.

e. Harmful Gender Norms

Gender stereotypes are often used to justify violence against women. Cultural norms

often dictate that men are aggressive, controlling, and dominant, while women are

docile, subservient, and rely on men as providers. These norms can foster a culture

of abuse outright, such as early and forced marriage or female genital mutilation,the latter spurred by outdated and harmful notions of female sexuality and virginity.

Self-assessment 12.4

1. What are the deepest root causes of gender-based violence?

a. Poverty

b. Abuse of power, inequality between men and women and disrespect for

human rights

c. Lack of education

d. Abuse of power and poverty

e. War

2. What impacts do conflict and natural disaster have on GBV? (Choose all

that apply):

a. Women and girls have to travel further to get necessary resources and are

therefore exposed to violenceb. Militarization leads to more violence

c. There are more opportunities for sexual exploitation

d. Social and support structures breakdown which makes everyone morevulnerable

12.5. The primary victims and survivors of Gender Based

ViolenceLearning activity 12.5

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. Describe what you see in picture A

b. Describe if any, relationship between picture A and picture B anddifferentiate primary victim from other ones

Both the terms of survivor and victim are used for a person who experienced

GBV and often used interchangeably. The term “victim” is often used in the legal

and medical sectors, recognizing that many forms of GBV are crimes. The term

“survivor” is generally preferred in the psychological and social support sectors

because it implies resiliency.

Gender-based violence is a widespread problem that affects males and females.

It disproportionately affects women and girls as a result of power imbalances

stemming from gendered power structural perceptions of masculinity and femininity

that create a rank order of gender.In case of domestic violence, children can be

affected by violence committed against their mothers, and they themselves can be

abused by the perpetrator, which can often be their fathers or stepfathers.

Persons who have been separated from their family or community, and or lack

access to shelter, education and livelihood opportunities, are among those most

at risk of GBV. This includes Children, especially unaccompanied minors, fostered

children, female and child heads-of-households, boys and girls in foster families or

other care arrangements, persons with mental and or physical disabilities, persons

in detention, house girls, single mothers, economically disempowered people, junior

staff, students, less privileged community members particularly those of minority

groups, asylum seekers, refugees and internally displaced people and girls and

boys born to rape victims/survivors. Women are the primary victim of GBV becausethey are usually second class, culturally considered inferior.

Self-assessment 12.5

1. True or false? GBV affect only women and girls as culturally considered

inferior

2. Children X and Y assist a domestic GVB. What kind of victim are they?3. Contrast the terms of victim and survivor with regard to GBV.

12.6 The main GBV perpetratorsLearning activity 12.6

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What is common to all the images above?

b. Describe what you see in each picture and attempt to establish therelationship between the individuals observed

A perpetrator is an individual, group, or institution that inflicts, supports, or

condones act of GBV or other types of abuse against a person or group of persons.

Generally, perpetrators include those individuals with real or perceived power,

persons in decision making positions or persons in authority. Anyone can be a GVB

perpetrator though primary GBV perpetrators are men and boys who often use

violence to assert or maintain their privileges, power and control over others.

GBV is usually perpetrated by persons who hold a position of power or control others,

whether in the private or public sphere. In most cases, those responsible are known

to the victim/survivor, such as intimate partners, family members, friends, domestic

staff and influential community members who are in positions of authority (teachers,

community or religious leaders, politicians). Others in positions of authority, such as

police or prison officials, and members of armed forces and groups, are frequently

responsible for such acts, in particular in times of armed conflict. In some cases,

this has also included humanitarian workers and peacekeepers. Furthermore, by

depicting women and girls negatively in their products, musicians, storytellers, and

other artists unconsciously promote GBV along with the role of mass media in

diffusing these.

• Intimate partners (husbands, wives, boyfriends, and girlfriends) may

perpetrate various murder, physical assault, marital rape, date rape, battery,

sexual violence, neglect, vandalism of property, confiscation of property,

forced sodomy, among, etc.

• Family member and friends; a category of perpetrators that is usually not

reported, may perpetrate incest, battery, trafficking, exposure to pornography,

neglect, denial of education, female genital mutilation, etc.

• Influential community members: This category of GBV perpetrator includes

people who enjoy positions of authority that they can easily abuse such

teachers, community leaders, politicians, religious leaders and business

owners. Examples of GBV perpetrated include sexual exploitation, sexual

harassment, forced prostitution, battery, and trafficking. Because of fear of

retaliation, loss of privileges, or pressure to protect the perpetrator’s honour;

survivors may find it difficult to report them.

• Security forces (soldiers, police officers, guards): This category holds the

authority to give and deny rights and privileges which they can eventually

abuse to perpetrate sexual extortion, arbitrary arrest, extrajudicial killing,

violating people who report to them, and concealing evidence.

• Institutions may perpetrate GBV by omission or commission. Institutions,

for example, might provide discriminatory social services that preserve and

expand gender inequalities, such as withholding information, delaying or

rejecting medical treatment, paying uneven wages for the same labor, and

obstructing justice. They may also fail to prevent or respond to GBV, and may

even institutionalize cultures that favor GBV.

• Humanitarian assistance workers: they hold positions of great authority and

command access to vast resources, including money, influence, food, and

basic services; unfortunately, some use this power to commit GBV, especially

sexual exploitation and abuse.Self-assessment 12.6

1. Explain the role of mass media in promoting acts of GBV

2. True or false?

• Religious leaders are respected man of God therefore clean from

perpetrating GBV

• Perpetrators are always unknown to their victims

• From fear of repercussion, survivor of GBV perpetrated by community

leaders are less likely to be reported

3. Which category of GBV perpetrators is associated with female genitalmutilation?

12.7. Interventions for GBVLearning activity 12.7

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. According to you understanding, describe what you see image A, B, C

b. Establish if any, relationship across images A, B and C

c. With reference to observed images, explain what can be the interventionsfor GBV

Combating gender-based violence requires an understanding of its causes and

contributing factors, which often also serve as barriers to effective prevention and

response.

There is a growing awareness and evidence that men and boys, in partnership with

women and girls, can play a significant role. Engaging men and boys as part of the

solution, instead of approaching them as perpetrators, is most effective.

a. The responsibility of the country

The country has primary responsibility for preventing and responding to genderbased

violence. This includes taking all necessary legislative, administrative,

judicial and other measures to prevent, investigate and punish acts of gender-based

violence, whether in the home, the workplace, the community, while in custody, or

in situations of armed conflict, and provide adequate care, treatment and support

to victims/survivors.

To that effect country should, for ensure the following:

• Criminalize all acts of gender-based violence and ensure that national law,

policies and practices adequately respect and protect human rights without

discrimination of any kind, including on grounds of gender.

• Investigate allegations of GBV thoroughly and effectively, prosecute and

punish those responsible, and provide adequate protection, care, treatment

and support to victims/survivors, including access to legal counseling, health

care, psycho-social support, rehabilitation and compensation for the harm

suffered.

• Take measures to eliminate all beliefs and practices that discriminate against

women or sanction violence and abuse, including any cultural, social,

religious, economic and legal practices.

• Take action to empower women and strengthen their personal, legal, social

and economic independence

b. The role of human rights and humanitarian actors

While primary responsibility lies with the national authorities, human rights and

humanitarian actors also play an important role in preventing and responding to

GVB. In addition to ensuring an effective GBV response from the beginning of an

emergency, this entails ensuring that gender concerns are adequately integrated

into and mainstreamed at all levels of the humanitarian response. Human rights and

humanitarian actors, as well as peace-keepers, must not under any circumstances,

encourage or engage in any form of sexual exploitation or abuse.

c. Role of community

This is through community groups (especially existing women’s groups); trusted

individuals (people who have been champions to speak out about positive male

norms, and the unacceptability of GBV); religious leaders and community leaders.

These groups may involve relevant community members and deploy resources

depending to the context. Using male engagement approaches is also one of

important aspects community intervention focus on. Additionally, engage key

individuals and organizations who are already working in the community.

d. The health institutions

They should think of ways to include the tracking of GBV-related incidents or

related norms within their programs and consider including activities that have the

potential to prevent GBV. Partnering with organizations that have GBV expertise

to provide GBV-related trainings to various groups they work with e.g. producer

groups, mother’s groups, etc. and allocate resources to GBV-specific inquiries and

trainings.

Working with local organizations that have expertise in facilitating single-sex safe

spaces for critical reflection on men’s/women’s own experiences of gender norms

and expectations, followed by opportunities for mixed sex dialogue and reflection.

They can also engage men and boys in addressing harmful culture norms and

promoting gender equality, accessing health services and policy/program

development. Fully participation and involvement of men and boys in increasing

public awareness of the value of all children and strengthen self-image, self-esteem

for all children. This can also be a great opportunity to improving the welfare of all

children, especially in regard to health, nutrition, and education including gender

education at family level. By doing so, health institution may help eliminating all

root causes of son preference, which result in female infanticide and prenatal sexselection.

Self-assessment 12.7

1. Outline at least 3 measures to be taken by our country as a primary

responsibility for preventing and responding to gender-based violence?

2. The strategies to engage men and boys in addressing harmful culture

norms and promoting Gender equality include: (Select all that apply)

a. Involving men and boys in policy/program development

b. Mainstreaming men engage philosophy into existing programs

c. Fully participation and involvement of men and boys in increasing public

awareness of the value of all childrend. No educational the welfare of all children

12.8. National guidelines for GBV preventionLearning activity 12.8

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. What do you see in the above images?b. Attempt to relate image A and image B

12.8.1 Introduction

Considering that GBV affects disproportionately women and causes harm not only

to the individuals experiencing violence, but also to their families, communities,

and the socio-economic wellbeing of the national as a whole, the government

of Rwanda has taken significant steps in addressing including the enactment of

laws and policies against GBV. With zero tolerance to any form of GBV, GBV is

criminalized in Rwanda since 2008 and is currently under Law No 68/2018 of

30/08/2018, which defines four types of GBV: bodily (physical), economic, sexual

and psychological.

Current national policy against GBV, introduce in 2011 and seeks to progressively

eliminate GBV through the development of a preventive, protective, supportive

and transformative environment. This policy acknowledges GBV as a cross-cutting

issue, thus a multi-sectoral approach is required to tackle it with the Ministry of

Gender and Family Promotion (MIGEPROF) holding primary responsibility for

policy implementation, dissemination, and coordination.

To address GBV, a strong partnership combining different ministries and other

government as well as private institutions, academic instructions, civil society

organisations, among others was established with each one having a key role to play.

For example the ministry of health is responsible of ensuring that the appropriate

policies and programmes are in place so that victims of GBV are able to access

appropriate services, ensuring an integrated human rights-based approach into

reproductive health services and scaling up ISANGE one stop centers; MIGEPROF

in collaboration with the Ministry of Local Government are responsible for facilitating

and coordinating gender mainstreaming initiatives at the district and sector levels;

etc.

Strategic areas addressed under this policy include: prevention strategies (i.e.

foster a prevention focused environment where GBV is not tolerated in society

and reduce vulnerability of most at risk groups to GBV); response strategies (i.e.

provide comprehensive services to victims of GBV and improve accountability

and eliminate impunity for GBV); and building coordination, monitoring systems

and expand the evidence available on GBV (i.e. build coordination and monitoring

systems and expand evidence available on GBV in Rwanda).

12.8.2. Implementation

Areas various actors intervene in include but not limited to:

a. Assessment, analysis and strategic planning related to the GBV – they

participate in identification of champions to catalyze processes of GBV

prevention, mitigation and effective immediate response across all clusters

and or sectors of humanitarian action. Make available any existing data on

affected populations, any risks of exposure to GBV for inclusion in response

strategies and to inform initial assessments.

b. Resources mobilization – they work with donors and express the importance

of providing resources for life-saving GBV interventions and for targeted

prevention and mitigation interventions programmes.

c. Coordination with others humanitarian sectors – to promote the guidelines

and related tools in inter-sectoral emergency preparedness meetings to

ensure all decision makers are aware of and have access to GBV prevention

guidance relevant to their clusters/sectors and geographic areas.

d. Monitoring and evaluation – identify at least one relevant indicator from

each area that require regular monitoring reports on actions and results taken

to prevent and mitigate GBV. They may include GBV as a standing agenda

item in government reporting meetings and integrate indicators from the

guidelines in assessments and evaluations while engaging the community

and partner organizations.

e. Involve relevant community members - this enables the community to learn

about how the program will operate and offer information on how the program

may positively and/or negatively impact community norms and existing gender

roles and inequalities in preventing GBV. Engage all members of affected

communities; this includes the leadership and meaningful participation of

women and girls alongside men and boys in all awareness.

f. Education, teaching and learning level – Some of the contemporary issues

that should be taught in the social studies programmes include law-related

education, family life education and peace education. This can enable the

existing social studies curriculum to equip students to have awareness of and

development of attitudes and values for combating gender-based violence.

Law-related education should aim at developing an understanding of the

basic legal concepts such as justice, authority, freedom, privacy, equality,

honesty and fairness.

g. Involvement of different sectors: Utilizing a multi-sectoral approach to

combating GBV is beneficial for establishing a comprehensive strategy i.e.

community anti-GBV committees, school-based anti-GBV clubs, community

policing, etc. However, many entities have reported a need for greater

effectiveness of local mechanisms that address GBV such as “Umugoroba

w’Ababyeyi” and “Inshuti z’Umuryango”, largely due to a need for capacity

building and adequate resources to implement their actions.

h. Communications and Information Sharing – they may appoint focal points

within relevant government bodies to drive and monitor awareness of how

the guidelines can be used to strengthen GBV prevention, mitigation andresponse throughout humanitarian action.

Self-assessment 12.8

1. Describe the national guiding elements for gender based violence

prevention?

2. Explain why it is important to involve relevant community members as a

guideline to prevent GBV?

3. List the 3 elements of the implementation guideline action for GBVprevention

12.9 Professional behavior in managing GBV casesLearning activity 12.9

Carefully observe the above images and attempt the following questions:

a. Describe what you see in image A, B and C

b. With reference to the above images, what do you think GBV interventionsinclude?

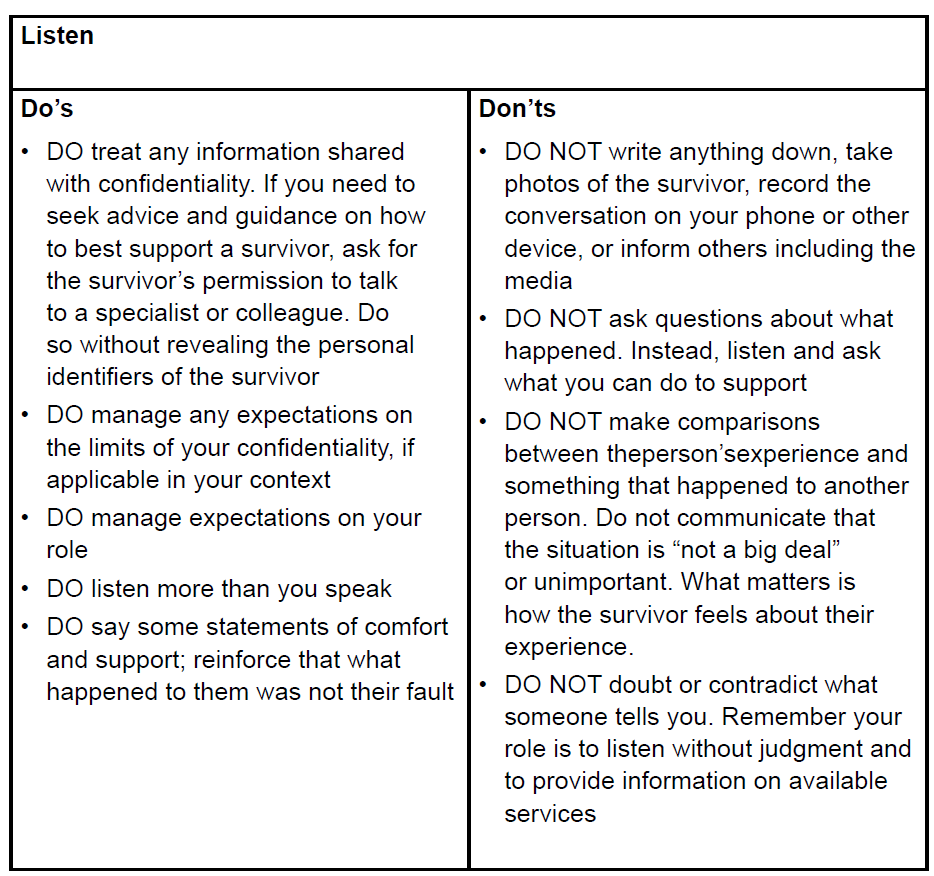

The health professional must always keep in mind that the safety and security of

the affected person is of primary importance. Four guiding principal for managing

the GBV cases include but not limited to (1) Right to dignity and self-determination,

(2) Right to confidentiality, (3) Non-discrimination, and (4) Right to safety.

The wishes, rights and dignity of GBV survivors must be respected at all times. All

information of the affected person and her/his family must be kept confidential and

will only be shared with those who need to know, with the explicit consent of the

survivor. Those with whom the information might be shared include Police, Medical

hospital staff, Officers of agencies with a protection mandate (e.g. UNHCR or

UNICEF) or otherwise involved in addressing needs of victims, among others. Along

with support and management of the cases, first line support requires that health

professionals are patient, do not pressure women to talk about their experiences,

and ensure that women are given information and access to resources.

Goals and guidelines elements for managing GBV cases with providingcentered

care Establish a relationship with the survivor, Promote the survivor’s

emotional and physical safety, Build trust, Helps the survivor restore some control

over her life. Be non-judgmental, supportive, and validating, provide practical care

and support that responds to her concerns, but does not intrude.

During history taking and examination: Informed consent is one of the most

important elements to obtain from a patient before beginning the examination and

documentation. Health professionals first need to obtain informed consent from the

patient on all aspects of the consultation. This means explaining all aspects of the

consultation to the patient, so that she understands all her options and is able to

make informed decisions about further management.

Ask about her history of violence, listen carefully, but do not pressure her to talk

(care should be taken when discussing sensitive topics while interpreters are

involved). Help her access information about resources, including legal and other

services that she might think helpful. Assist her to increase safety for herself and

her children, where needed. Ensure the consultation is conducted in private and

informing the limits of confidentiality.

In cases of sexual violence, the following information should be added: the

time since assault and type of assault, the risk of pregnancy, the risk of HIV and

other sexually transmitted infections, the woman’s/girl mental health status.

when interviewing the patient about GBV, health professionals should: ask

her to tell in her own words what happened, avoid unnecessary interruptions

and ask questions for clarification only after she has completed her account , be

thorough, bearing in mind that some patients may intentionally avoid particularly

embarrassing ,details of the assault, such as details of oral sexual contact or anal

penetration, use open-ended questions and avoid questions starting with “why”,

which tends to imply blame. Address patient questions and concerns in a nonjudgmental,

empathic manner, for instance, through using a very calm tone of

voice, maintaining eye contact as culturally appropriate and avoiding expressing

shock or disbelief. After taking the history, health professionals should only conduct

a complete physical examination (head-to-toe; for sexual violence also including

the patient’s genitalia) if appropriate.

When undertaking medical examination and providing medical or nursing care:

Following disclosure of GBV, health professionals should undertake a medical

examination, if appropriate, and provide medical or nursing care. Throughout the

entire process of medical examination and care, health providers need to take into

account that survivors of sexual violence are often in a heightened state of awareness

and very emotional after an assault. Throughout the physical examination inform

the patient what you plan do next and ask permission. Always let her know when

and where touching will occur; show and explain the instruments and collection

materials.

Documenting GBV cases: Health providers have a professional obligation to

record the details of any consultation It is not only a professional obligation to

record details, but is also important for medical records, since medical records can

be used in court as evidence. Documenting the health consequences may help

the court with its decision-making as well as provide information about past and

present violence. Recording injuries, documentation of violence protect the identity

and safety of a survivor. Do not write down, take pictures or verbally share any

personal/identifying information about a survivor or their experience, including with

your supervisor. Put phones and computers away to avoid concern that a survivor’s

voice is being recorded.The Do’s, Don’ts of professional management of GBV cases

Don’t assume that confidentiality is a given; take steps to ensure confidentiality.

Don’t let staff give out personal phone numbers or become a case manager. Don’t

examine a person without her consent may result in criminal prosecution of healthcare professionals.

Self-assessment 12.9

1. What is the goal of survivor centered case management? (Choose one

answer):

a. Establish a relationship with the survivor

b. Promote the survivor’s emotional and physical safety

c. Build trust

d. Helps the survivor restore some control over her life

2. What are the 4 guiding principles of GBV case management? (choose 4

answers)

a. Right to be happy

b. Right to dignity and self-determination

c. Mandatory reporting

d. Right to confidentiality

e. Non-discrimination

f. f. Legal information

g. Right to safety3. What is the Non-discrimination mean?

12.10 The consequences of GBVLearning activity 12.10

Carefully observe the above images and describe and give sense what you

see.

GBV has significant and far-reaching consequences that affect not only GBV

survivors but also their families, communities, and society. For instance at societal

level, GBV can lead to social stigma, rejection, break-up of families, homelessness,

dispossession, and destitution. GBV survivors are at high risk of severe and longlasting

health problems and even loss of life. There are different categorizations of

GBV repercussions, with each variety of GBV having its own, even though there

are some overlaps.

a. Physical consequences – Physically, victims may suffer various injuries,

including bleeding, wounds, burns, fractures, permanent disfigurement,

physical disability, stunted physical growth (for children), fistula or even death.

b. Sexual and reproductive health consequences – GBV has grave sexual

and reproductive health consequences. It can deter survivors from seeking

reproductive health and family planning services. There is a strong between

GBV and HIV among persons living with HIV/AIDS. Consequences of GBV

under this category including:

• Unplanned pregnancies and children

• Induced, unsanitary, and dangerous abortions

• Sexually transmitted infections, including HIV

• Barrenness due to disease and injury

• Sexual dysfunction

• Injury to reproductive organs, leading to lifelong malfunctions

• Early pregnancy

• Destabilization of the menstrual cycle

• Deformed genitalia and related health complications

• Loss of sexual desire and painful sexual intercourse

• Infertility

c. Emotional/psychological consequences – these include but not limited

to anxiety, depression, anger or hostility, low self-esteem, suicide (attempts

and actual suicide), self-harm, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fear,

shame, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, dissociation and loss of memory,

inability to trust others, especially in cases of intimate partner violence, sleep

disturbance, emotional detachment, etc.

d. Social and cultural consequences – they include among others:

• Alienation and rejection

• Loss of respect and dignity among peers, family, and community

• Aggressive behaviours that may be accompanied by retaliatory attitudes

• Break of social networks of support

• Rejection, stigmatization, and neglect of children resulting from rape or incest

• Early marriage in a bid to reclaim family’s honour with associated loss of

children’s right to education as a result of early marriage

• Stigma and discrimination for life

• Repeat violation due to perceived vulnerability

• Breakdown in heterosexual relationships, including marriage

• Identity crisis for children born out of sexual violation

• Exclusion of victims from important communal events such as burial rites

• Poor performance and increased dropping out of school

• Slow rate of development due to withdrawal syndrome and limited interaction

with peers

e. Economic consequences – GBV costs survivors, their families, and society

at large both directly (such as treatment, visits to the hospital doctor and other

health services) and indirectly such as lost productivity, absenteeism, reduced

employability (as a result of reduced education/incapacity to focus at work),

disability, decreased quality of life and premature death. Other economic

repercussions include among others; reduced investments as savings are

diverted to medical treatment, costs incurred by the criminal justice system

in apprehending and prosecuting offenders and costs associated with casemanagement, counseling and psycho-social support, etc.

Self-assessment 12.10

1. List at least 4 sexual and health reproductive consequences of GBV

2. Contrast direct and indirect economic consequences of GVB

3. True or false? GBV consequences are always in line with the type or formof GBV

End unit 12 assessment

1. Contrast gender and sex

2. How gender identity differ from gender orientation

3. Explain how legal factor influence GBV

4. Among other consequences of GBV, there are economic repercussions.

Explain how these affect the survivors and their families and the society

at large.

5. True or false?

a. Domestic violence is common occurrence and might be the most under

reported form of GBV

b. In general, gender differences are permanent and universal

c. Gender refers to the natural differences that separate men and women

d. GBV survivors are at high risk of severe and long-lasting health problems

and even loss of life

e. Men access healthcare services more frequently than do women and

respond positively to received services

a. Health promotion and disease prevention messages target frequently

women

6. The following are social and cultural repercussions of GBV except:

a. Rejection, stigmatization, and neglect of children resulting from rape or

incest

b. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

c. Breakdown in heterosexual relationships, including marriage

d. Aggressive behaviours that may be accompanied by retaliatory attitudes

7. Give 3 examples of GBV forms that are likely to be perpetrated by

Influential community members

8. Why is human trafficking classified as physical GBV?

9. What is the country responsibility in GBV prevention?10. List four professional guiding principles for GBV case management

REFERENCES

A Jones, S. (2012). First Aid, Survival and CPR. F.A. Davis Company.

Aid, F., & Version, B. (2021). Australia Wide First Aid eBook (Version 6.1). Australia

Wide First Aid.

Amercan Heart Association. (2016). Basic life support: Provider Manual (First

Edition). American Heart Association.

Baranoski, S., & Ayello, E. A. (2012). Wound Care Essentials: Practice Principles

(3rd ed.). Wolters Kluwer health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

BrainKart.com, 2018 guidelines and types of bandages retrieved online at:https://

www.brainkart.com/article/Uses Guidelines-and-Types-of-bandages-_2308/ on

09th Sept 2021

Cowart, S. L. and Stachura, M. A. X. E. (2000) ‘Laboratory’, in Clinical Methods:

The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition, pp. 653–657.

Cunningham, J. et al. (2019) ‘A review of the WHO malaria rapid diagnostic test

product testing programme (2008-2018): Performance, procurement and policy’,

Malaria Journal. BioMed Central, 18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-3028-z.

Directorate of Forests Government of West Bengal. (2016). Manual for First Aid.

1–30.

Disque, K. (2021). CPR, AED & First Aid: Provider Handbook. 2020-2025 Guidelines

and Standards Satori Continuum Publishing.

Emmett, M. (2014) ‘Albuminuria’, Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 81(6), p.

345. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.81c.06006.

Güemes M, Rahman SA, Hussain K. What is a normal blood glucose? Arch Dis

Child. 2016;101(6):569–74.

Indian Red Cross society. (2016). Indian first aid manual 2016. 7th editio, 1–346.

https://www.indianredcross.org/publications/FA-manual.pdf

Lao National First Aid Curriculum Development Technical Working Group. (2014).

Trainer’ s Manual First Aid for National Village Health Volunteers.

Lewis, S.L, Dirksen, T.R, Heitkemper, M. McLean and Bucher, L. (2014). Medical

Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems. 9th Edition

Lojpur, M. (n.d.). First Aid to the Injured.

Loren Nell Melton Stein & Connie J. Hollen (2021) Concept-Based Clinical Nursing

Skills: Fundamental to Advanced. Elsevier Inc.

New Zeland Red Cross. (2021). Essential First Aid. ttps://doi.org/10.1136/

bmj.2.4318.456-a

Piazza, G. M. (2014). First Aid Manual: The Step by Step Guide for Everyone. (5th

ed.). DK Publishing.

Pickering D, Marsden J. How to measure blood glucose Understanding and caring

for a Schiotz tonometer. Community Eye Heal. 2014;27(87):56–7.

Razzak RA, Alshaiji AF, Qareeballa AA, Mohamed MW, Bagust J, Docherty S. Highnormal

blood glucose levels may be associated with decreased spatial perception

in young healthy adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1–12.

Semanoff A. A Case Study - Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Nurs. 2018;37(9):1–4.

Slachta, P. A. (2012). Wound care made incredibly visual! (2nd ed.). Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins.

Steggall, M. J. (2007) ‘Urine samples and urinalysis.’, Nursing standard (Royal

College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987), 22(14–16), pp. 42–45. doi: 10.7748/

ns2007.12.22.14.42.c6303.

Stein, L. N. M., & Hollen, C. J. (2021). Concept-Based Clinical Nursing Skills:

Fundamental to Advanced (First). Elsevier Inc.

Visser, L. S., & Montejano, A. S. (2018). Guide for Triage and Emergency Nurses:

Chief Complaints with High Risk Presentations (1st ed., Vol. 148). Springer

Publishing Company, LLC.

Wound, Ostomy and Continence Society (2016). Core Curriculum: Wound

Management. Wolters Kluwer health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Yancey CC, O’Rourke MC. Emergency Department Triage. [Updated 2021 Jul 30].

In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557583/?report=classic

Erica Roth, C. (2021). Everything you need to know about Low blood pressure.

Healthline

Preston, W., & Kelly, C. (2017). Respiratory Nursing at a Glance. John Wiley and

Sons, Ltd.

Nettina, S. M. (2019). Lippincott manual of nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters

Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Harding, M. M., Kwong, J., Roberts, D., Hagler, D., & Reinisch, C. (2020). Lewis’ s

Medical-Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (11th

ed.). Elsevier, Inc.

Zealand N, Defence C, Management E. General Rescue Manual New Zealand Civil

Defence Emergency Management Table of Contents. 2020.

Spray A, Merry W, Sweeting G, Colwell D. Ground Search & Rescue (GSAR)

Participant Manual. Justice Inst. Br. Columbia. 2018.

Kentucky Emergency Management. SAR Field Search Methods: Search Techniques

Used by Trained Teams in the Field. 2019;8. Available from: https://kyem.ky.gov/

Who We Are/Documents/SAR Field Search Methods.pdf

Search S, Rescuers CL, Resources OC, Aid F, Composition T. Chapter 1: Search

and Rescue. 2021;1–16. Available from: http://www.sdmassam.nic.in/download/

searchandrescuemanual.pdf

Wong J, Robinson C. Urban search and rescue technology needs: identification of

needs. Fed Emerg Manag Agency Natl Inst Justice. 2016;73.

A Jones, S. (2012). First Aid, Survival and CPR. F.A. Davis Company.[1]

Aid, F., & Version, B. (2021). Australia Wide First Aid eBook (Version 6.1). Australia

Wide First Aid.

Directorate of Forests Government of West Bengal. (2016). Manual for First Aid.

1–30. Disque, K. (2021).

Lao National First Aid Curriculum Development Technical Working Group. (2014).

Trainer’s Manual First Aid for National Village Health Volunteers.

Erica Roth, C. (2021). Everything you need to know about Low blood pressure.

Healthline

Preston, W., & Kelly, C. (2017). Respiratory Nursing at a Glance. John Wiley and

Sons, Ltd.

Nettina, S. M. (2019). Lippincott manual of nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters

Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Harding, M. M., Kwong, J., Roberts, D., Hagler, D., & Reinisch, C. (2020). Lewis’ s

Medical-Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems (11th

ed.). Elsevier, Inc.

Goolsby, M. J., & Grubbs, L. (2018). Advanced assessment interpreting findings

and formulating differential diagnoses. FA Davis

Forbes, H., & Watt, E. (2015). Jarvis’s physical examination and health assessment.

Elsevier Health Sciences.

Berman, A., Snyder, S. J., Kozier, B., Erb, G., Levett-Jones, T., Dwyer, T., & Stanley,

D. (2010). Kozier and Erb’s fundamentals of nursing (Vol. 1). Pearson Australia.

Hogan-Quigley, B., & Palm, M. L. (2021). Bates’ nursing guide to physical

examination and history taking. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Wiliams, L. (2011). Wilkins. Health assessment made incredibly visual!

Honjo, K. (2004). Social epidemiology: Definition, history, and research examples.

Environmental health and preventive medicine, 9(5), 193-199.

Broom, D. H. (1984). The social distribution of illness: is Australia more equal?.

Social science & medicine, 18(11), 909-917.

Wikler D. Personal and social responsibility for health. Ethics Int Aff 20021647–55.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Callahan D, Koenig B, Minkler M. Promoting health and preventing disease: ethical

demands and social challenges. In: Callahan D, ed. Promoting healthy behavior.

Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2000153–170.

WHO. (2013). Family as Centre of Health Development Family as Centre of Health

Development. (March), 18–20.

Bauml, J., Frobose, T., Kraemer, S., Rentrop, M., &Pitschel-Walz, F. (2006).

Psychoeducation: A basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with

schizophrenia and their families. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32, 11–19.

Farber, B., Berano, K., &Capobianco, J. (2004). Clients’ perceptions of the process

and consequences of self-disclosure in psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 51, 340–346.

Guilbeault, L. (2020). What is the therapist’s role in non-directive therapy? Better

Help. Retrieved August 4, 2020 from https://www.betterhelp.com/advice/therapy/

what-is-the-therapists-role-in-nondirective-therapy/

Hill, C., & Knox, S. (2001). Self-disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research,

Practice, Training, 38, 413–417.

Horvath, A. (2001). The alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice,

Training, 38, 365–372.

Lambert, M. J. (1991). Introduction to psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy

Research: An International Review of Programmatic Studies. Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Meyers, L. (2014). Connecting with clients. Counseling Today, 18. Retrieved August

2020 from www.ct.counseling.org/2014/08/connecting-with-clients/#

Prochaska, J., & Norcross, J. (2001). Stages of change. Psychotherapy: Theory,

Research, Practice, Training, 38, 443–448.

Rennie, D. (1994). Clients’ accounts of resistance in counseling: A qualitative

analysis. Canadian Journal of Counseling, 28, 43–57.

Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality

change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103.

Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy.

New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Schueller, S. M. (2009). Promoting wellness: Integrating community and positive

psychology. Journal of CommunityPsychology, 37, 922–937.

Sexton, T. L. (1996). The relevance of counseling outcome research: Current trends

and practical implications. Journal of Counseling and Development, 74, 590–600.

Detels, R., Gulliford, M., Karim, Q. A., & Tan, C. C. (2015). Oxford Textbook of

Global Public Health. In Global Public Health: A New Era (6th ed.). Oxford University

Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199236626.001.0001

GACA. (2018). Providing a safe and protective environment for the child: Additional

Training Module & Activity Facilitation Guide On Adolescence, Sexual And

Reproductive Health, Gender And Sexual And Gender Based Violence (SGBV).

UNICEF Ghana and Department of Community Development of the Ministry of

Local Government and Rural Development.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2015). How to Support Survivors of Violence

when a GBV Actor is not available in your Area: A Step-By-Step Pocket Guide for

Humanitarian PractitionerS. September 2015, 2–3. https://gbvguidelines.org/wp/

wp-content/uploads/2018/03/GBV_Background_Note021718.pdf

Jacobsen, K. H. (2019). Introduction to global health (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett

Learning, LLC.

MIGEPROF. (2011). Gender Based Violence Training Module. Republic of Rwanda

MIGEPROF. (2011). National Policy against Gender-Based Violence.July. Republic

of Rwanda http://www.migeprof.gov.rw/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/

GBV_Policy-2_1_.pdf

Ostlin, P., Eckermann, E., Mishra, U. S., Nkowane, M., &Wallstam, E. (2007).

Gender and health promotion: a multisectoral policy approach. Health Promotion

International, 21, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal048

Skolnik, R. (2016). Global Health 101 (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC.

UNHCR Global Protection Cluster Working Group.(2019). Handbook for the

Protection of Internally Displaced Persons Goals.UNHCR. https://doi.org/10.12968/

bjon.2019.28.10.607

UNHCR. (2016). SGBV Prevention and Response - Training Package. UNHCR.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPREGTOPENVIRONMENT/Resources/

Water_Pollution_Emergency_Final_EN.pdf

United Nations Country Team in Kenya. (2019). Gender Based Violence Training

Ressource Pack: A Standardized Bearers, Stakeholders, Training Tool for Duty and

Rights Holders. UN Women Kenya Country Office.

United Nations Country Team in Kenya. (2019). Gender Based Violence Training

Ressource Pack: A Standardized Bearers, Stakeholders, Training Tool for Duty and

Rights Holders. UN Women Kenya Country Office.

United Nations Country Team in Kenya. (2019). Gender Based Violence Training

Ressource Pack: A Standardized Bearers, Stakeholders, Training Tool for Duty and

Rights Holders. UN Women Kenya Country Office.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2020). Gender and non-communicable diseasesin Europe: Analysis of STEPS data. World Health Organization.