UNIT 5MANAGEMENT OF THE SECOND AND THIRD STAGES OF LABOUR

Key Unit competence: Manage women in the second and third stages of labor

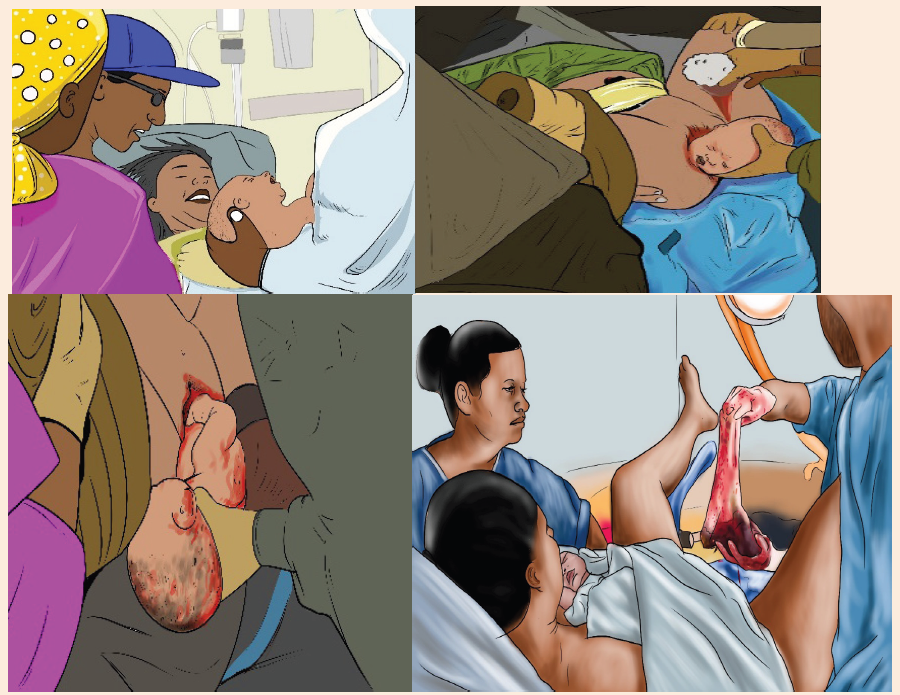

Introductory activity 5Carefully observe the pictures below and answer the questions below:

1. Based on the above pictures, how many stages of labour does a woman

go through?

2. According to what you know, what happens in each stage of labour?

3. Mention some medications that can be administered to the woman during

labour and circumstances in which these medications are indicated.

4. Which complications may likely occur during labour?

5. What can a nurse do to support a woman having labour related

complications?

5.1. Management of the second stage of labour5.1.1 Introduction to the second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.1

Watch the video titled ‘Managing Second Stage and Active Management

of Third Stage of Labour Perfect’ found on this link: https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=Yq8RJkLPOmc and answer the following questions:

a) What do you understand by the term ‘second stage of labour’?

b) Briefly describe the physiological changes occurring during the secondstage of labour?

Second stage of labor, referred to as the pushing stage, starts when the expectant

woman’s cervix is fully dilated and ends with the birth of the baby. The woman is

actively involved in giving birth with the support of skilled birth attendants.

Effective descent of the foetus through the birth canal involves not only position

and presentation but also a number of different positional alternatives termed as

‘cardinal movements’. These changes enable the smallest diameter of the foetal

head to pass through the vagina based on the diameter of the mother’s pelvis.

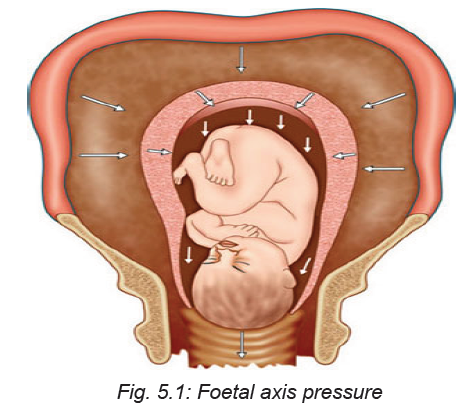

For this to happen, during the second stage of labour, a number of physiological

changes occur to facilitate the birth of the baby. The contractile power of the uterus

is intensified because the foetus is closely applied to the uterus, as some of the

amniotic fluid has leaked. The upper uterine segment becomes short and thick

because of the retraction of uterine muscle fibres. During each contraction, its force

is transmitted through the long axis of the foetus, directing it through the birth canaland this is termed as foetal axis pressure.

The foetal axis pressure leads to expulsive action of the abdominal muscles and

diaphragm. The abdominal muscles and diaphragm contracts, known as ‘bearing

down’ or ‘pushing’. Initially it is reflex, but can be aided by voluntary effort. With the

distension of the pelvic floor by the presenting part, the expulsive action becomes

involuntary.

Another physiological change that occur during the second stage of labour is the

displacement of the pelvic floor. The bladder is drawn up into the abdomen, the

vagina is dilated by the advancing head, the posterior segment of the pelvic floor is

pushed downwards in front of the presenting part and the reaction is compressed

by the advancing head. Further changes that takes place is pouting and gaping of

the anus, thinning out of the perineum and lengthening of the posterior wall of the

birth canal.

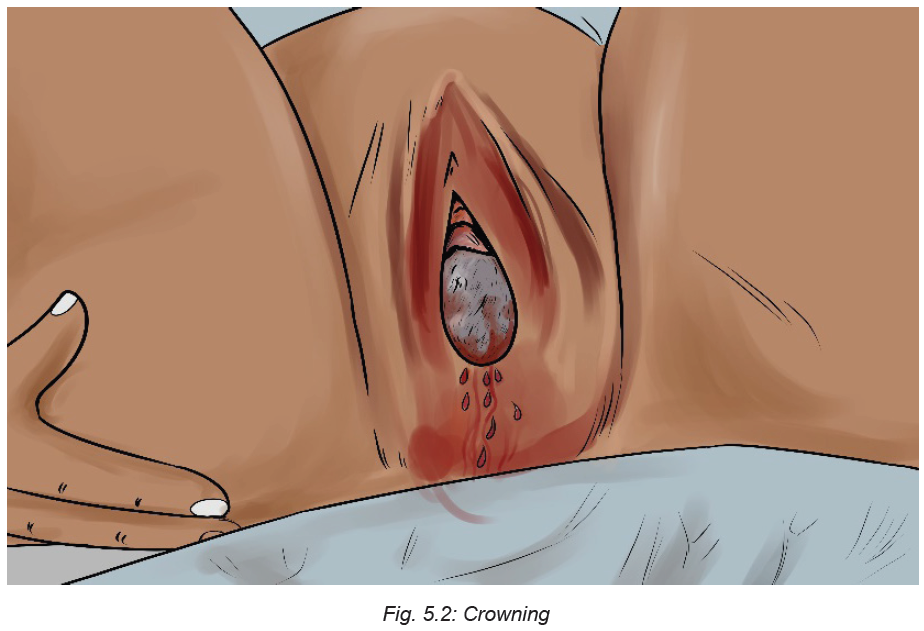

During the normal spontaneous vaginal birth, the next physiological change that

occurs is the expulsion of the foetus. As the woman collects her efforts to birth, the

baby’s head becomes visible at the opening of her birth canal and this biologicalmovement is called crowning (see picture below).

The head is born by extension, after which the shoulders and body are born, with

the remaining amniotic fluid.

Self-assessment activity 5.1.1

i. Define the following terms:

– crowning

– Bearing down

– Fetal axis pressure

ii. Describe the physiological stages involved in the birth of the baby during

the second stage of labour.

5.1.2 Mechanism of labour during the second stage

Learning Activity 5.1.2

Watch the video titled ‘Mechanism of Normal Labor’ found at: https://www.youtube.

com/watch?v=AKFS8I-uwHA and answer the following questions.

i. Based on the video you have watched, outline the movements that happen

before the baby is born.

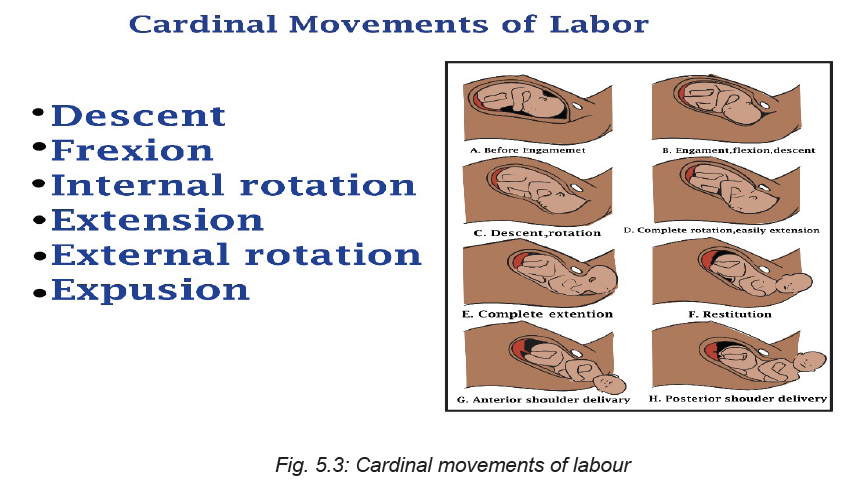

The second stage of labour involves a number of cardinal movements leading to

the birth of the baby. These cardinal movements involve positional changes that

are effected by the foetus during the birth process. They encompass engagement,

descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion asshown in the picture below.

a. Engagement

Engagement occurs when the largest transverse diameter of the head of the

foetus had passed through the pelvic inlet. When the foetal head is engaged, a

small part of the head is palpable above the pelvic brim. The healthcare provider

assesses the engagement of the presenting part during abdominal examination.

When engagement has started, the skilled birth attendant should take care of the

following:

• Assess the woman after an hour if there are no signs of foetal distress and the

maternal observations are normal.

• If the head has not engaged after waiting 1 hour, the skilled birth attendants

must carefully examine the patient for cephalopelvic disproportion which may

be present as a result of a big foetus or an abnormal presentation of the foetal

head. In this case, the skilled birth attendant refer the mother to advanced

care.

b. Descent

Descent is the downward movement of the biparietal diameter of the foetal head

within the pelvic inlet. Full descent occurs when the foetal head protrudes beyond

the dilated cervix and touches the posterior vaginal floor. Descent occurs because

of pressure on the foetus by the uterine fundus. As the pressure of the foetal head

presses on the sacral nerves at the pelvic floor, the labouring woman will experience

the typical “pushing sensation,” which occurs with labour. As a woman contracts her

abdominal muscles with pushing, this aids descent.

c. Flexion

As descent is completed and the foetal head touches the pelvic floor, the head

bends forward onto the chest, causing the smallest anteroposterior diameter (the

suboccipitobregmatic diameter) to present to the birth canal. Flexion is also aided

by abdominal muscle contraction during pushing.

d. Internal Rotation

During descent, the biparietal diameter of the fetal skull was aligned to fit through

the anteroposterior diameter of the mother’s pelvis. The head flexes at the end of

descent, the occiput rotates thus the head is brought into the best relationship to

the outlet of the pelvis, or the anteroposterior diameter is now in the anteroposterior

plane of the pelvis. This movement brings the shoulders, coming next, into the

optimal position to enter the inlet, or puts the widest diameter of the shoulders (a

transverse one) in line with the wide transverse diameter of the inlet.

e. Extension

When the occiput of the fetal head is born, the back of the neck stops beneath the

pubic arch and acts as a pivot for the rest of the head. The head extends and the

foremost parts of the head, the face and chin is born.

f. External Rotation

In external rotation, almost immediately after the head of the foetus is born, the

head rotates a final time (from the anteroposterior position it is assumed to enter

the outlet) back to the diagonal or transverse position of the early part of labor.

This brings the after coming shoulders into an anteroposterior position, which is

best for entering the outlet. The anterior shoulder is born first, assisted perhaps by

downward flexion of the foetal head.

g. Expulsion

Once the shoulders are born, the rest of the baby is born easily and smoothly

because of its smaller size. This movement, called expulsion, is the end of thepelvic division of labor.

Self-assessment 5.1.2

i) Define the following terms:

b) Engagement

c) External rotation

d) Descent

ii) As a nurse, what can you do when you notice that engagement has started?

Homework 5.1

Read Chapter about the management of the second stage of labour in book titled

‘The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module’.

Focus on pages 3, 4, and 5 of the chapter.

5.1.3. Factors affecting the second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.3

i) Based on what you have read from the book titled ‘The Continuous

Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module’, what are thebiological factors that may influence the second stage of labour?

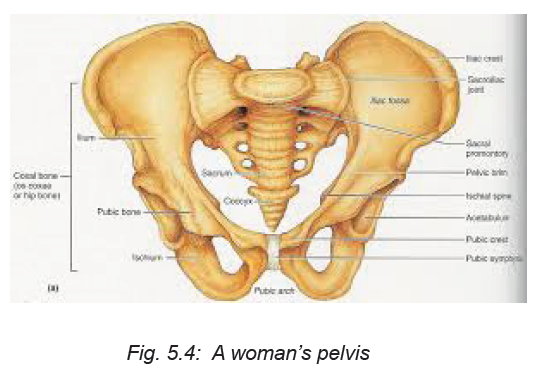

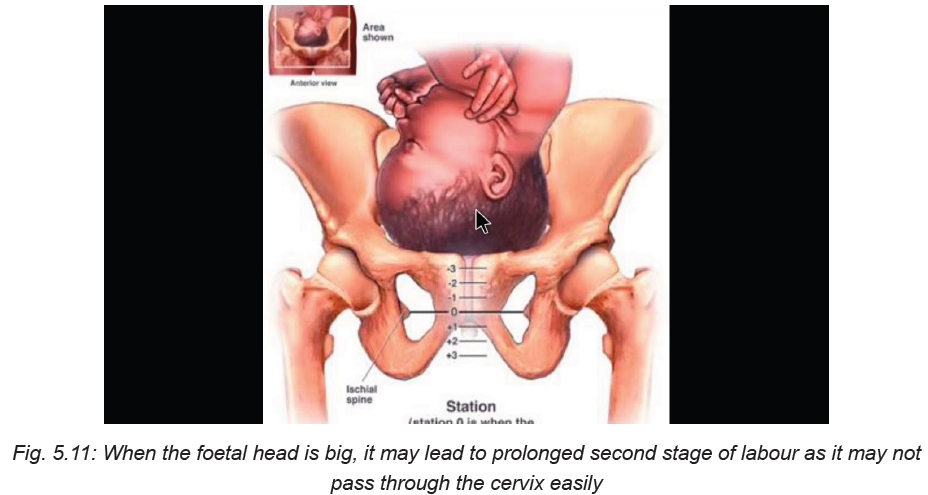

A successful second stage of labour depends on four integrated factors; namely the

passage, passenger, power, and position.A. The passage (a woman’s pelvis)

The passageway refers to the route a foetus must travel through from the uterus to

the cervix, vagina, and to the external perineum. The bony pelvis through which the

foetus must pass is divided into three sections: the inlet, mid-pelvis (pelvic cavity),

and outlet. Each of these pelvic components has a unique shape and dimension

through which the foetus must manoeuvre to be born vaginally. Because the cervix

and vagina are contained inside the bony pelvis, the foetus must also pass through

the bony pelvic ring. The two pelvic measurements that are important to determine

the adequacy of the pelvis are the diagonal conjugate (the anteroposterior diameter

of the inlet) and the transverse diameter of the outlet.

B. The passenger

The passenger can be defined as the foetus and the foetal membranes. The body

part of the foetus that has the widest diameter is the head, so this is the part least

likely to be able to pass through the pelvic ring in normal vaginal births. For birth

to occur normally, the passenger should be of appropriate size (not big for the

woman’s pelvis) and in an advantageous position and presentation. Whether a

foetal skull can pass through the woman’s pelvis depends on both its structure

(bones, fontanelles, and suture lines) and its alignment with the pelvis.

C. The powers of labour:

The powers of labour refer to the quality of contractions including frequency,

strength, and duration.

D. Position

Foetal position refers to the relationship of an arbitrarily chosen portion of the foetal

presenting part (Occiput, sacrum, mentum /chin or sinciput) to the right or left side

of the mother’s birth canal. The foetal presenting part may be in either the left or

right position to the four quadrants of the maternal pelvis, the foetal positions may

be left occipital (LO) and right occipital( RO), left mental (LM) and right mental( LM)

, and left sacral (LS) and right sacral presentations.

Self-assessment 5.1.3

With examples, explain how these factors can influence the second stage of

labour:

b) Passage

c) Passenger

d) The powers of labour.

Homework 5.2

Go to the internet and watch the video titled ‘Management of Second Stage of

Labour | Normal Labour | Nursing Lecture’ using this link: https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=hHHA4vfWMcA

5.1.4. Nursing Management of the woman during the secondstage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.4

Based on the video you have watched in homework, answer the following

questions.

i) Why is it very important for a skilled birth attendant to manage the second

stage of labour adequately?

ii) What assessments and observation should a skilled birth attendant perform

during the second stage of labour?

Promoting the health of women in labour is one of the measures to reduce maternal

morbidity, mortality and ensuring universal access to reproductive health services.

During the second stage of labour, a labouring woman needs optimum care in order

to prevent any complications that may affect her and that of the baby. The nurse at

this stage must coach quality pushing and support delivery.

It is very important for the skilled birth attendant to recognise the commencement of

the second stage. There are many probable signs that indicate the transition from

first to second stage as outlined below.

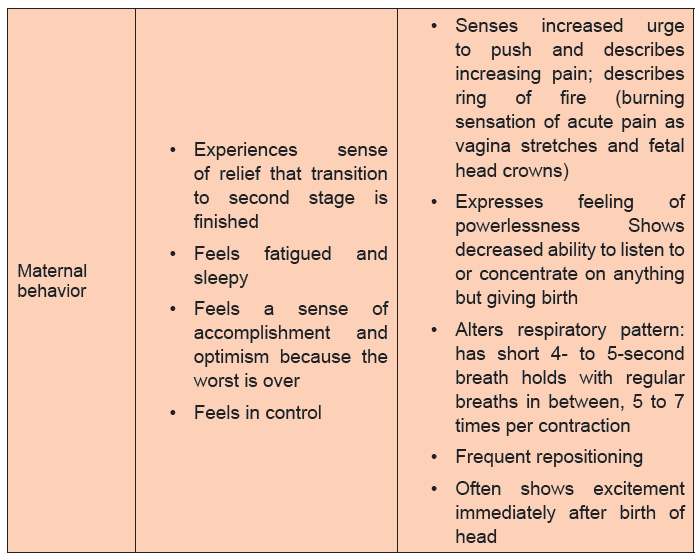

Table 5.1 Probable signs of the second stage oflabour

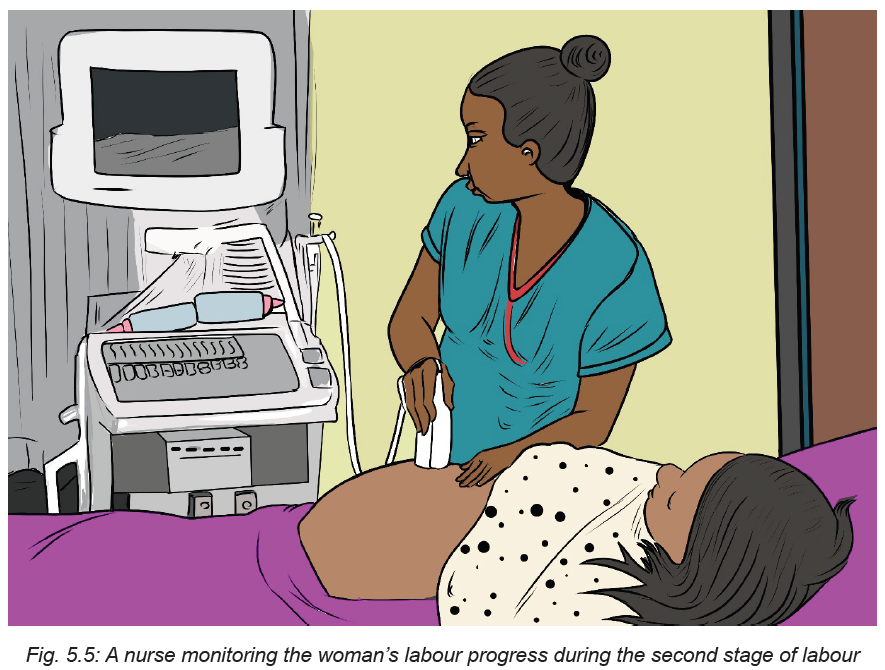

During the second stage of labour, the skilled birth attendant has to observe

maternal and foetal condition in order to ensure the safety of the second stage of

labour. Factors to observe include uterine conditions, the descent, foetal condition,

and maternal condition.

Regarding the uterine condition, the skilled birth attendant has to assess the

strength, length and frequency of contractions should be assessed continuously. In

comparison to the first stage, contractions are stronger and their duration is longer

(1 minute), with a longer resting phase.

As for the descent, the progress is observed by noting the descent of the foetus. It

accelerates during the active phase. If there is delay, a vaginal examination should

be performed to note whether internal rotation of the head has taken place to note

the station of the presenting part and for presence of caput succedaneum.

The skilled birth attendant also has to assess any presence of the colour of liquor

amnii (for meconeum staining) and changes in foetal heart pattern. The skilled birth

attendant has to perform intermittent auscultation of the foetal heart rate immediately

after a contraction for at least 1 minute, at least every 5 minutes. The caring team

has to palpate the woman’s pulse every 15 minutes to differentiate between the

two heartbeats. Ongoing consideration should be given to the woman’s position,

hydration, coping strategies and pain relief throughout the second stage.

Women in the second stage of labour will feel exhausted, and may not have the

ability to care for themselves. As a skilled birth attendant, you will have to give best

possible care to the woman and help her to cope with this stage of labour. The care

to offer encompass the following:

• Maternal comfort and hygiene

• Sponge the face and neck of the mother with a wet towel.

• Provide ice-chips or sips of water

• Apply moisturizing cream to lips to prevent dryness and cracking.

• Encourage to pass urine at the beginning of the second stage if she hasn’t

done it during the late first stage.

• Apply measures like massaging, encourage deep breathing, distraction, etc.,

to relieve pain.

• Reassure the woman. Encourage her to bear down only when instructed to.

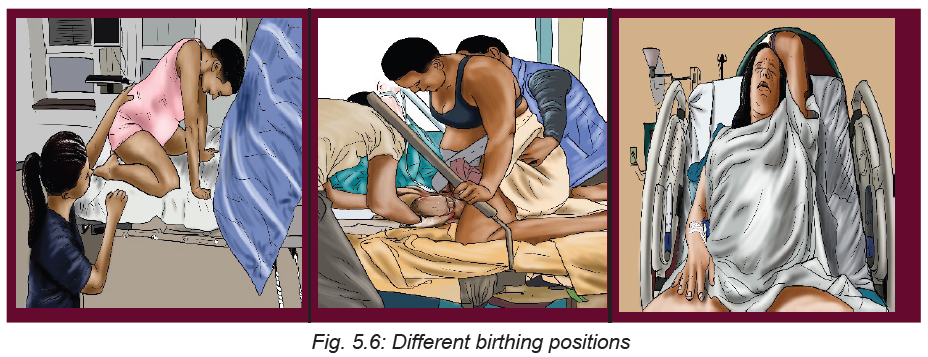

As the woman prepares to give birth, the skilled birth attendant will have to give

the woman an appropriate position, to enable the birth process to be completed

smoothly. There are several factors that will affect the decision for adopting a specific

position, i.e., the maternal and foetal condition, the need for frequent monitoring,

the woman’s personal choice, the environment’s safety, privacy in the room, and

the birth attendant’s confidence to assist in the birthing process.

Some of the positions that can be adopted include semi-recumbent or supported

sitting position, squatting, kneeling or standing positions, and left lateral position asshown in the images below.

As for the supported sitting position, it increases the efficiency of the uterine

contractions and prevents hypotension and reduced placental perfusion. The

squatting position increases the transverse diameter by 1 cm and the anteroposterior

diameter by 2 cm, thereby resulting in easy delivery. The kneeling and standing

position also contribute to easy delivery. The left lateral position enables the skilled

birth attendant to view the perineum clearly. This position is useful for women who

cannot abduct their hips.

The woman should be helped to avoid ‘active pushing’ before the vertex is visible

at the vulva. This will allow the mother to conserve her effort and will permit the

vaginal tissues to stretch passively. Once the head becomes visible, the mother

should be encouraged to follow her own inclinations in relation to expulsive efforts.

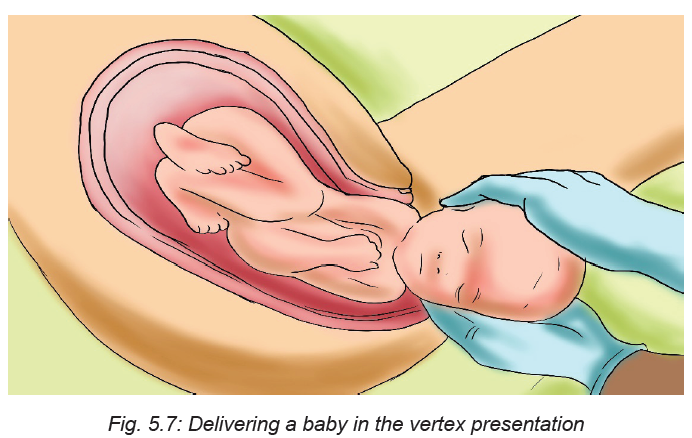

The next step will involve the skilled birth attendant to facilitate the birth of the baby.

In this book, the entire process of conducting births is discussed in the skills lab and

practical checklist. To avoid complications in the mother as well as the newborn,one must conduct the delivery very skillfully in a vertex presentation.

The two phases of delivery of the foetus in a vertex presentation are:

i) Delivery of the head, and

ii) Delivery of the shoulders and body.

The principles to be kept in mind while conducting the delivery is to minimise

maternal and foetal trauma and ensure a safe delivery for the baby. Principle of

asepsis must be maintained. The perineum is swabbed and the woman is draped

with sterile towels. A pad is used to cover the anus. With each contraction the head

descends and the superficial muscles of the pelvic floor especially the transverse

perineal muscles are visible. During the resting phase, the head recedes, thereby

the muscle thins gradually. The skilled birth attendant places her fingers on the

advancing head to monitor descent and prevent expulsive crowning.

During the birth, the skilled birth attendant must help the mother to prevent the

tears in the vaginal opening. Some health care providers do not touch the vagina or

baby at all during the birth. This is a good practice because interference can lead

to infection, injury, or bleeding. But the healthcare providers may be able to prevent

tears by supporting perineum during the birth.

Self-assessment 5.1.4

i) What precautions should a skilled birth attendant take while delivering the

baby?

ii) What can you base on to determine if the second stage of labour has

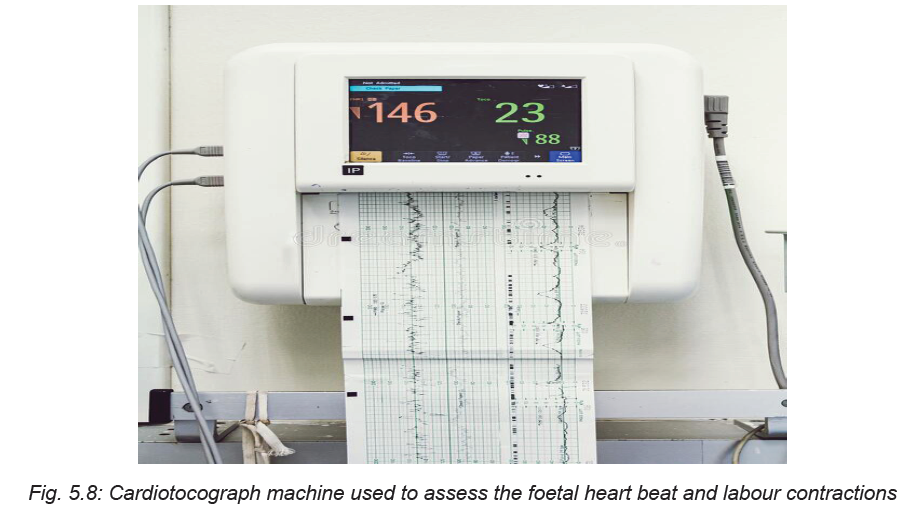

started?5.1.5. Assessing foetal wellbeing during the second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.5

a. What is the role of the machine pictured above?

b. Why is it important to assess the foetal wellbeing during the second stage

of labour? of labour?

A foetus is at a high risk of being exposed to maximum hypoxic stress during second

stage of labour, due to a combination of maternal expulsive efforts and their impact

on the uteroplacental circulation, as well as repetitive and sustained compression

of the umbilical cord and the foetal head. Since this can lead to physiologic stress

for the foetus and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and foetal death, frequent

monitoring of foetal status is performed to detect early the onset of foetal hypoxic

stress. It is recommended to monitor foetal heart rate in low risk women for every

15 minutes in the active phase of the first stage of labour and every 5 minutes in

the second stage of labour and it is easiest to hear, by auscultating immediately

after a contraction. The care provider should have the skills to interpret the foetal

heart rate and take appropriate action when needed. Foetal heart rate can range

between 120 and 160 times a minute during labour.

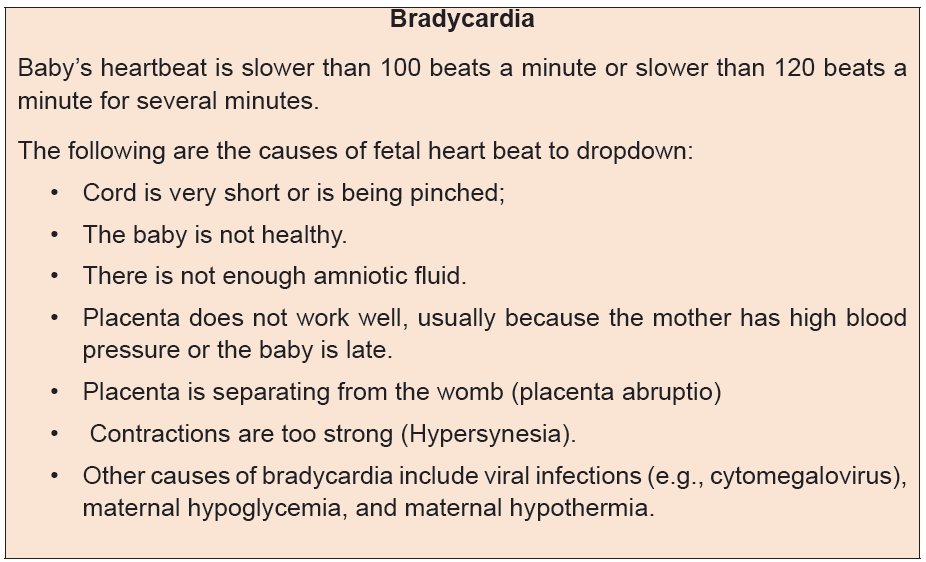

At times, the heart may be as fast as 180 beats per minute (Tachycardia) or as slow

as 100 beats per minute (Bradycardia). Once these abnormal heart beat trends

are detected, the skilled attendant has to intervene in order to normalise these

irregularities in the foetal heart beating by for instance assisting the mother to lie incomfortable position.

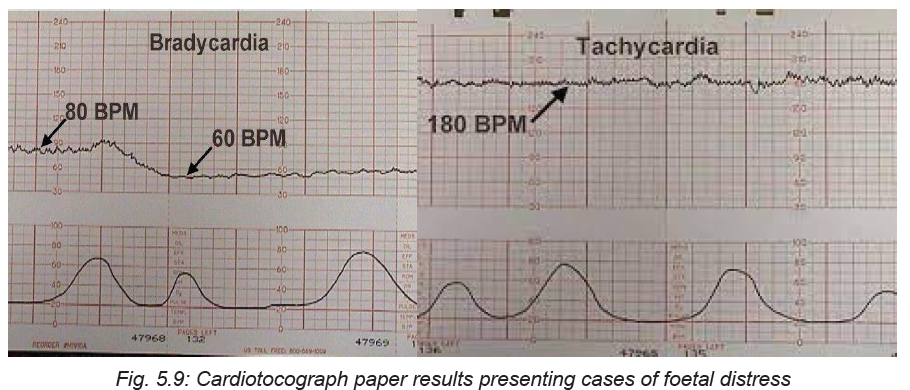

Table 5.2: Causes of bradycardia

When the baby’s heartbeat is slow after a contraction is over but then goes back to

normal, the baby may be having trouble. The skilled attendant has to listen to several

contractions in a row. If the heartbeat is normal after most other contractions have

ended, there is a possibility that the baby’s heart is beating normally. However, the

skilled birth attendants should ask the mother to change position to take pressure

off the cord. They also have to listen again after she moves to see if this helps, and

keep checking the baby’s heartbeat often during the rest of labour to see if it slows

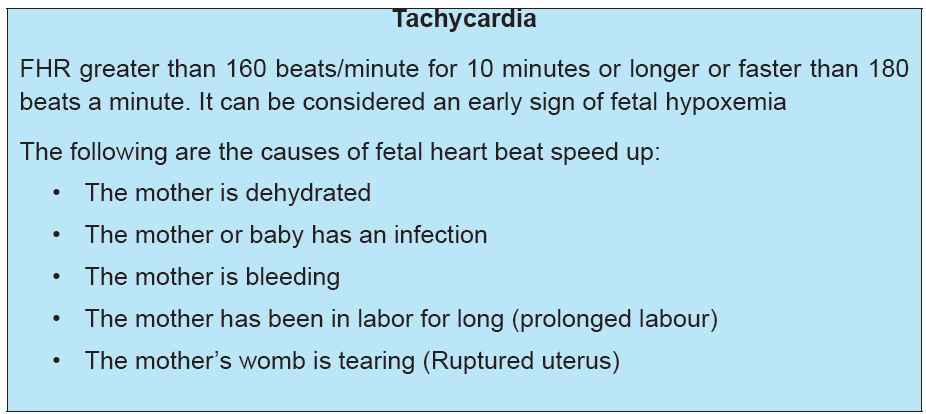

down again.Table 5.3: causes of tachycardia

If the baby’s heartbeat stays fast for 20 minutes (or 5 contractions), get medical

help.

Self-assessment 5.1.5

i) What is the normal foetal heart beat?

ii) Mention some of the conditions that cause foetal bradycardia.

iii) Mention some of the conditions that cause foetal tachycardia.

iv) What is the range of a slowing foetal heart rate?

v) What is the range of a speedy foetal heart beat?5.1.6. Recognising foetal compromise during second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.6

Referring to the two CTG paper results shown on the above images, answer the

following questions:

i) What is the difference between the two results of the foetal heart displayed?

ii) Which of the above results may require medical attention and why?

Foetal compromise or foetal distress is when the baby is not well due to inadequate

oxygen during labour. Foetal compromise is caused by a number of factors

including placental insufficiency, uterine hyperstimulation, maternal hypotension,

cord compression, placental abruption, uterine rupture, and foetal sepsis. It can

also be caused by problems with the umbilical cord namely cord compression.

Foetal distress can also occur in case the mother has a health condition such as

diabetes, kidney disease or cholestasis. At some point, foetal distress can happen

as a result of contractions that are too strong or too close together.

Foetal distress is diagnosed by reading the baby’s heart rate. Another sign is

to check if there is meconium in the amniotic fluid. If the amniotic fluid is green

or brown, this signals the presence of meconium. A slow heart rate, or unusual

patterns in the heart rate, may signal foetal distress. Continuous cardiotocograph

(CTG) monitoring is recommended when either risk factors for foetal compromise

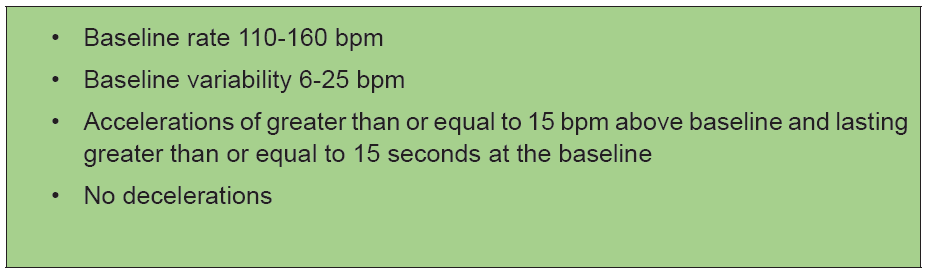

have been detected antenatally, at the onset of labour or develop during labour. A

CTG associated with a low probability of foetal compromise and is characterised by

the features presented in following tablesTable 5.4: CTG Characteristics

The following features are unlikely associated with foetal compromise when

occurring in isolation:

– Baseline rate 100-109 bpm

– Reduced or reducing baseline variability (3-5 bpm)

– Absence of accelerations

– Early decelerations

– Variable decelerations without complicating features.

– The following features may be associated with significant fetal compromise

and require further action:

– Baseline fetal tachycardia >160 bpm

– Rising baseline fetal heart rate (FHR), including where the fetal heart rate

remains within normal range

– Complicated variable decelerations

– Late decelerations

– Prolonged decelerations (a fall in baseline FHR for >90 seconds and up to 5

minutes).

The first step to manage foetal compromise is to give the mother oxygen and oral

and intra venous fluids. In addition to this, the mother can be assisted to move

position, such as turning onto one side, can reduce the baby’s distress. If the

woman had been given drugs to speed up labour, these may be stopped if there are

signs of foetal distress. If it is a natural labour, the woman can be given medicationto slow down the contractions. A baby in foetal distress needs to be born quickly.

Self-assessment 5.1.6

i) What are the maternal related possible causes of foetal compromise during

the second stage of labour?

ii) When the foetal heart rate is recognised as abnormal?iii) What major interventions are performed if foetal distress is diagnosed?

5.1.7. Duration of the second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.7

Using your prior knowledge, answer the following questions:

i) What is the estimated duration of second stage of labour?

ii) What are the maternal and foetal factors influence the second stage of

labour?

The second stage of labour commences with full dilation of the cervix and ends

with the birth of the baby. The median duration of second stage of labour is 50

to 60 minutes in nulliparous women and 20 to 30 minutes in multiparous women.

The upper limits for the duration of normal second-stage labour are 2 hours for

nulliparous women and 1 hour for multiparous women. The duration of the second

stage is variable and the length of this stage may be influenced by several factors

such as parity, maternal size and foetal weight; position, and descent; the type

and amount of pain relief administered, the frequency, intensity, and duration of

contractions, maternal efforts in pushing, and the support the woman receives

during labour.

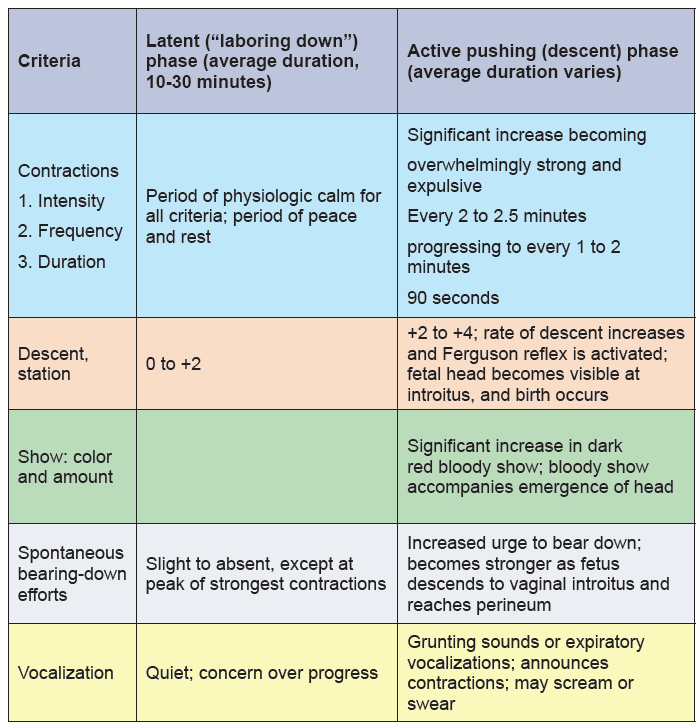

The second stage of labour is subdivide into two phases: the latent or labouring

down phase (period of rest and relative calm) and the active pushing or descent

phase (woman has strong urges to bear down). Maternal verbal and nonverbal

behaviours, uterine activity, the urge to bear down, and foetal descent characterize

these two phases. Table 5.5 presents the expected maternal progress for each

phase and the average duration it may take.

Table 5.5. Expected Maternal Progress in theSecond Stage of Labour

Self-assessment 5.1.7

i. Using concrete examples, discuss how long is the second stage of labour

expected to last?

ii. What are the phases of the second stage of labour?

iii. Outline the criteria used to characterise the phases of the second stage of

labour.

iv. How bearing down effort is differs from each other in those phases?v. What are the factors influencing the length of the second stage of labour?

5.1.8. Reducing risks during second stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.1.8

Using your prior knowledge, books, and the picture above, answer the following

questions

a) What risks may likely occur during the second stage of labour?

b) What is the main cause of risk during the second stage of labour?

The second stage of labour is very demanding for both the woman and the foetus.

When the second stage of labour is not optimally managed, the woman’s and

foetus’ life may be at risk. Complications that may occur during the second stage

of labour include but are not limited to abnormal foetal heart rate patterns, infection

particularly following membrane rupture, stillbirth, neonatal asphyxia, meconium

aspiration syndrome, fatigue, and neonatal birth injury example branchial plexus

paralysis. For the woman, some of the common risks that may occur during the

second stage of labour include chorioamionitis (membrane infection), tears (cervical

or perineal), urinary retention, increased rate of caesarean birth, and future urinary

incontinence.

Most of the risks that affect the woman and her baby result from prolonged labour.

For this reason, close monitoring and skills and capacity to offer timely intervention

are required for all births to prevent adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes such

as stillbirth and newborn complications arising from undetected hypoxia, as well as

maternal mortality and morbidity from complications such as vesicovaginal fistula,

genital tract lacerations, infection, haemorrhage, and worsening of hypertensive

disorders. In order to prevent complications associated with the delayed second

stage of labour, skilled birth attendants must not leave the labouring woman alone

after the late first stage has commenced.

Because of the increase in foetal lactate levels after the onset of active maternal

pushing, continued active maternal pushing for more than 60 minutes should be

avoided, unless a spontaneous vaginal birth is imminent and the foetal heart rate

monitoring does not show any evidence of ongoing foetal compromise. The skilled

birth attendants have to encourage active pushing once the woman’s urge to bear

down is present. They should assist the woman to adopt any position of their

preference for pushing, except lying supine which risks aortocaval compression

and reduced uteroplacental perfusion. The skilled birth attendants should listen

to the foetal heart rate frequently (at least 1 minute every 5 minutes) in between

contractions to detect bradycardia. The caring team also has to check the maternal

pulse and blood pressure, especially where there is a pre-existing problem of

hypertension, severe anaemia, intrapartum haemorrhage or cardiac disease. To

minimise prolonged second stage of labour, the frequency, strength and duration of

uterine contractions are observed, as well as the relaxation of the uterus between

contractions. The amniotic fluid is observed for meconium staining. The birth

attendant must not allow the mother’s bladder to become distended. The woman’s

bladder must always be assessed for fullness and she should be encouraged to

void if fullness of bladder is found.

Self-assessment 5.1.8

What precautions can be undertaken to prevent the risks occurring in the secondstage of labour?

5.2 Management of third stage of labour

5.2.1 Introduction to the third stage of labour

Learning Activity 5.2.1

Watch the video titled ‘Managing the Third Stage of Labour - Childbirth Series’

found on this link:and answer

the following questions:

i) What do you understand by the third stage of labour?

ii) What happens during the third stage of labour?

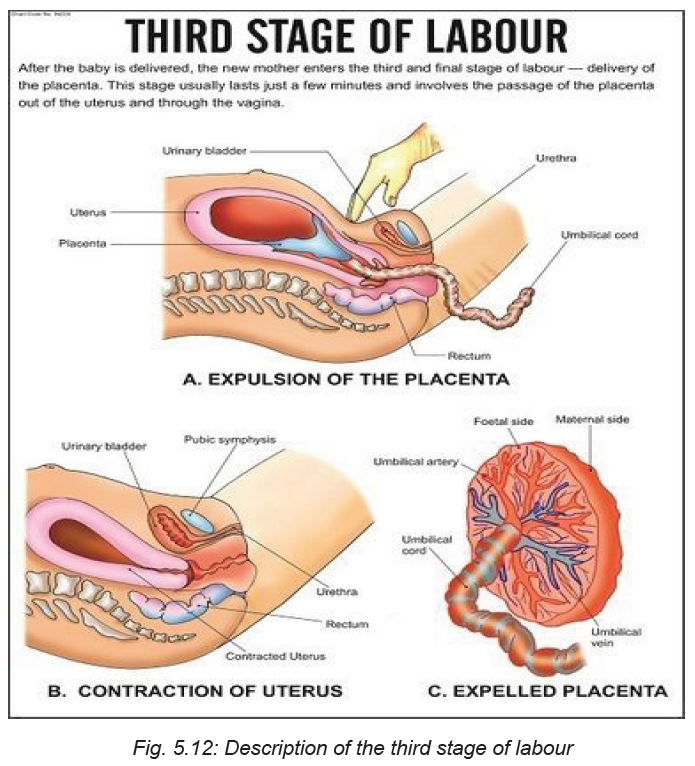

The third stage of labour is the period extending from the second stage of labour

the completed birth of the new-born until the completed delivery of the placenta.

Once a baby is born, the womb (uterus) continues to contract, causing the placenta

to separate from the wall of the uterus and then mother delivers it.

When the woman gives birth normally, the third stage is when natural physiological

processes spontaneously deliver the placenta and fetal membranes. For this to

happen without problem, the cervix must remain open and there needs to be good

uterine contractions. In the majority of cases, the processes occur in the following

order:

1. Separation of the placenta: The placenta separates from the wall of uterus.

As it detaches, blood from the tiny vessels in the placental bed begins to clot

between the placenta and the muscular wall of the uterus.

2. Descent of the placenta: After separation, the placenta moves down the

birth canal and through the dilated cervix.

3. Expulsion of the placenta: The placenta is completely expelled from the

birth canal.

This expulsion marks the end of the third stage of labour. Thereafter, the muscles

of the uterus continue to contract powerfully and thus compress the torn blood

vessels.

Thus the management of the third stage of labour entails the period after the birth

of the baby to help the uterus contract or return to normal, clamping the cord, and

controlled cord traction to deliver the placenta.

a) Why third stage of labour important in the care of the expectant woman

Most of the conditions that lead to maternal morbidity and even deaths occur during

the third stage of labour if the woman does not receive optimal care. Some of the

major contributors of maternal deaths, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis can be

associated with limited proper management of the third stage of labour. When the

placenta remains inside the uterus for longer than 30 minutes after the birth of the

baby due to inadequate uterine contractions, and the rapid retraction of the cervix

which traps the placenta into the uterus, and full bladder obstructing placental

delivery can all contribute to excessive bleeding after birth.

b) How is the third stage of labour managed?

There are two options applied to manage the third stage of labour: active management

and physiological management. The physiological management is general practised

in midwife-led units and in home births. This management approach of the third stage

of labour allows the placenta to be delivered only by pushing, gravity, contractions

and sometimes by nipple stimulation. This management technique does not rely

on the use of oxytocin injections. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut once it

has stopped pulsing or when the placenta comes out. Normally the physiologic

management of the third stage of labour takes up to one hour. This requires that

the health care team helps the mother to initiate skin-to-skin contact with the baby

while breastfeeding him/her in order to stimulate more natural oxytocin production.

The physiological management of the third stage of labour is only advised if there

is no risk for the woman to bleed heavily after the birth of the baby.

The second approach and which is mostly used especially in most developing

countries is the active management of the third stage of labour. This approach

is recommended by the World Health Organisation because of it is effective in

reducing the risks of the complications of the poor management of the third stage

of labour. When applying the active management of third stage of labour, the caring

team does not wait for the spontaneous placental delivery. Instead, the interventions

are prompt and follows the following sequential order:

• Just after the baby is born, the midwife/or nurse puts the baby on the mother’s

abdomen in skin to skin contact with her;

• The midwife or nurse clamps the baby’s umbilical cord at two sites and cuts

it in between;

• Check the uterus to find out if there is any second baby;

• In less than one minute, administer a uterotonic drug to make the uterus

contract more powerfully;

• Apply controlled cord traction;

• After delivering the place, immediately start massaging the uterus;

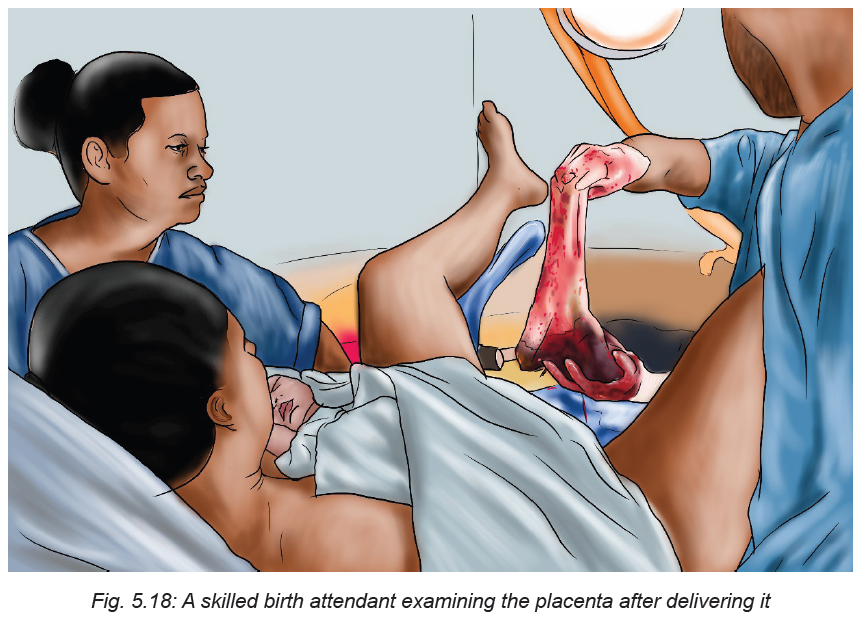

• Examine the placenta to make sure it is complete and there are no retained

parts of the placenta in the uterus;

• Examine the woman’s vagina, perineum and external genitalia for anylacerations and active bleeding.

Self-assessment 5.2.1

iii) Explain in orderly sequence the three processes characterising the third

stage of labour.

iv) Why is it important for health professionals to take much care when

managing the third stage of labour?

v) Mention at least three things that can happen if the third stage of labour is

not appropriately managed.

Homework 5.3

Go to the internet, read an extract about uterotonic drugs from the book titled

‘Uterotonic drugs to prevent postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis’found on this link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537857/

5.2.2. Administration of uterotonic drugs

Learning Activity 5.2.2

Based on the information you read in the book ‘Uterotonic drugs to prevent

postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis’, what do you understand by

the term ‘uterotonic drugs’?

i) Why is it important to administer uterotonic drugs during the third stage of

labour

ii) Mention some of the examples of uterotonic drugs you have read?

Introduction to uterotonic drugs

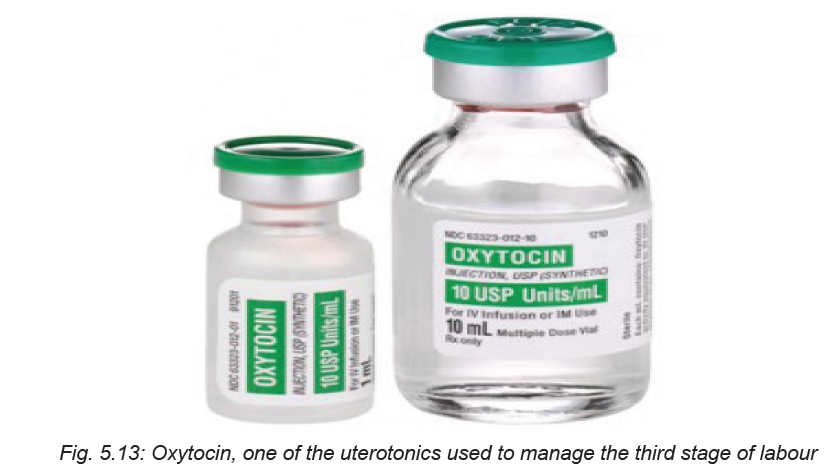

Uterotonic drugs are medications given to the woman in order to stimulate the uterus

to contract or to increase the frequency and intensity of the uterine contractions.

When administered, these drugs stimulate the placenta to separate from the

uterine wall to be delivered. Uterotonic drugs, when given to the woman during the

third stage of labour act as one of the interventions package to prevent postpartum

haemorrhage. Uterotonic drugs include oxytocin, ergometrine, misoprostol,

carbetocin, prostaglandins, and ergot alkaloids, but the three frequently used

uterotonic drugs are oxytocin, prostaglandins, and ergot alkaloids.Uterotonic drugs have a number of advantages as shown in figure below:

Table 5.6: Advantages of uterotonic drugs

How to give uterotonic drugs

The uterotonic drugs can be used in all stages of childbirth when needed. In the

case of the third stage of labour, the uterotonic drugs are indicated as one of the vital

interventions of the active management of third stage of labour. When providing

uterotonic drugs, the nurse has to consider the following:

1) Administer uterotonic drugs immediately after the birth of the baby before

performing cord clamping and cutting the cord.

2) Before giving uterotonic drug to the woman, the nurse has to perform

abdominal palpation to find out if there is no any other baby. This is because,

if for instance oxytocin is administered when there is a second baby, there is

a risk that the second baby could be trapped in the uterus.

3) Administration of uterotonic drug of the choice is given after confirmation

that no any other baby inside the uterus and is given with 1 minute after

childbirth. The uterotonic of choice is oxytocin 10IU IM. The dose given to

the woman is usually IM: 10 units if a woman has an IV when she gives birth.

The nurse can either give 10 IU IM or 5 IU by slow IV injection.

4) Controlled cord traction is applied with counter-pressure on the uterus to

deliver the placenta.

Any health worker administering or dispensing the uterotonic drug should be

authorized to do so and be trained in the proper use of the drug and management of

side and adverse effects. Clear documentation of administration of any uterotonic

drugs should be part of the woman’s medical record. Documentation includes the

time, route, and dosage of any medications given, as well as a record of any side

effects.

Contraindication of uterotonic drugs

Most of the uterotonic drugs have no known contraindications when administeredin the third stage of labour.

Self-assessment 5.2.2

i) Which uterotonic of choice is used in active management of third stage of

labour?

ii) What are the advantages of using uterotonic in third stage of labour?5.2.3. Cord clamping and cutting

Learning Activity 5.2.3

Watch the video found on this link:

and answer the following questions.

i) Why do you think it important to clamp the cord after the birth of baby?

ii) Based on what you have seen in the video, describe the steps involved incord clamping.

Introduction

The umbilical cord, is typically made up of two arteries and one vein and covered

in a thick gelatinous substance known as Wharton’s Jelly. The main function of

the umbilical cord is to pass oxygen and nutrients from the mom to the baby and

to transport waste away from the baby to the mother via the placenta. Most of the

time, there is no need to cut the cord right away. Leaving the cord attached will help

the baby to have enough iron in his blood. It will also keep the baby on his mother’s

belly where the baby belongs. When the baby is just born, the cord is fat and blue. If

you put your finger on it, you will feel it pulsating. This means the baby is still getting

oxygen from his mother.

When the placenta separates from the wall of the womb, the cord will get thin and

white and stop pulsating and at this time it will not be facilitating blood circulation to

the baby from the mother. As a result the cord can be clamped, usually after about

3 minutes in order to separate the baby from the placenta. When this is done, it

facilitates the baby’s organs to start adapting to the new environment other than its

mother’s womb.

There are two approaches of clamping the cord; i) early clamping which is usually

carried out in the first 60 seconds and ii) late cord clamping carried out more than

one minute after the birth of the baby or when the cord pulsation has stopped.

The latter approach, often called delayed umbilical cord clamping, according to the

World Health Organisation facilitates placental-to-new-born transfusion and results

in an increased neonatal blood volume at birth. In addition, delayed umbilical cord

clamping may be particularly relevant for infants living in low-resource settings with

less access to iron-rich foods and thus greater risk of anaemia.

Benefits of delayed cord clamping

The evidence further shows that delayed cord clamping can have immediate and

long term benefits for babies. In preterm infants, delayed umbilical cord clamping

is associated with significant neonatal benefits, including improved transitional

circulation, better establishment of red blood cell volume, decreased need for blood

transfusion, and lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular

haemorrhage. Furthermore, delayed cord clamping further promotes cerebral

oxygenation. For term infants, delayed cord clamping can provide adequate blood

volume and birth iron stores to the baby. It further increases haemoglobin amounts

in the term infants. For the mothers, delayed clamping can decrease the incidence

of retained placenta.

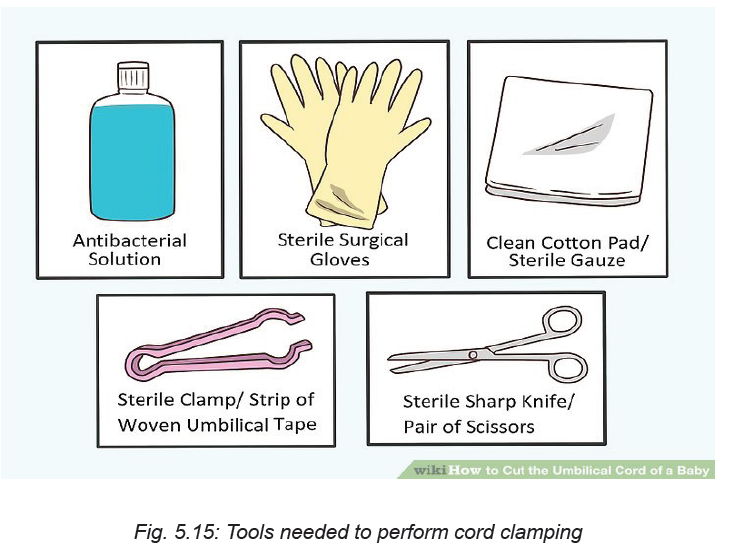

Procedure for cord clamping and cutting

Before starting the procedure of cord clamping and cutting, the health provider hasto make sure that he/she has access to the following medical supplies:

• An antibacterial solution.

• Sterile surgical gloves

• A clean cotton pad or (preferably) sterile gauze

• A sterile clamp or strip of woven umbilical tape

• A sterile sharp knife or pair of scissors

Once you have collected all the medical supplies together, the health provider has

to check if the cord is wrapped around the newborn’s neck.

If so, slide your finger under the cord and gently pull it over the newborn head. Next,

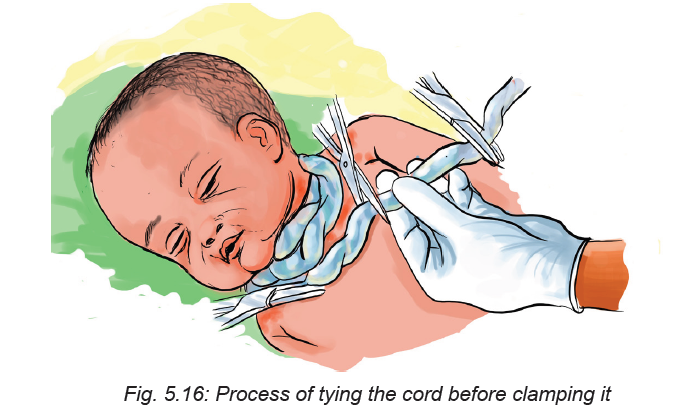

use sterile plastic clamps or sterile woven umbilical tape to tie off the cord (see the

image below).

Put the first tie of the clamps about 3 cm from the baby. The second tie should be

placed further away from the baby, about 5 centimetres from the first tie. Keep in mind

that although a pulse in the umbilical cord may stop shortly after delivery, significant

bleeding may still occur if the cord is not clamped or tied. Prepare the umbilical cord

by swabbing between the clamps or ties with antibacterial solution. You can use

betadine or chlorhexidine. This step should be done especially if delivery occurs

in a public or unhygienic setting. Use a sterile, sharp blade such as a scalpel or a

strong pair of scissors.

The umbilical cord is much tougher than it looks, and will feel like rubber or gristle.

Grasp the cord with a piece of gauze. The cord may be slippery so this will ensure

you have a firm grip on the cord.

Cut cleanly between the ties or clamps. Make sure you hold the cord firmly to

ensure the cut is clean.

Self-assessment 5.2.3

i) Define the term delayed cord clamping and explain why it is important to

delay cord clamping.

ii. What should a nurse do before clamping the cord?5.2.4 Controlled cord traction

Learning Activity 5.2.4

Watch the video titled ‘Placental delivery by controlled cord traction’ found on

this link:and answer the following

questions.

i) What do you understand by controlled cord traction?

ii) Why is important to perform controlled cord traction?

iii) Describe each step involved in controlled cord traction.

Controlled cord traction (CCT) can be defined as traction applied to the umbilical

cord once the woman’s uterus has contracted after the birth of her baby, and her

placenta is felt to have separated from the uterine wall. Counter-pressure is at the

same time applied to her uterus beneath her pubic bone until her placenta delivers.

Controlled cord traction is used to stabilise and deliver the placenta.

This method involves a number of steps in order the technique to be effectively

done.

Controlled cord traction involves the following steps:

• Clamp the cord close to the perineum and hold in with one hand.

• Place the other above the woman’s pubic bone and stabilise the uterus by

applying counter-pressure during controlled cord-traction

• Keep sight tension on the cord and wait for the strong uterine contraction (2-3

minutes) encourage the mother to push and very gently pull down the cord to

deliver the placenta and continue with counter-pressure to the uterus.

• If the placenta does not descend during 30-40 second of controlled cord

traction do not continue to pull on the cord.

• Gently hold the cord and wait until the uterus is well contracted again; with the

next contraction, repeat controlled cord traction with counter-pressure

• Never apply cord traction (pull) without applying counter traction (push) above

the pubic bone on a well-contracted uterus.

• As the placenta delivers, hold the placenta in two hands and gently turn it until

the membranes are twisted.

• Slowly pull to the placenta delivery

• If the membranes tear, gently examine the internal and external genitalia

wearing the sterile gloves and use sponge holding forceps to remove

fragments of membranes that are present.

• Examine carefully the placenta to rule out any missing portion of it, if you

suspect retained portions on maternal surface or tone membranes take

appropriate action.

Contraindication of controlled cord traction

The nurse should at all costs avoid controlled cord traction if there are no uterotonic

drugs available. Controlled cord traction is also contraindicated prior to signs of

separation of the placenta as this can cause partial placental separation, a rupturedcord, excessive bleeding, and/or uterine inversion.

Self-assessment 5.2.4

i. What should one avoid while doing controlled cord-traction?

ii. What important technique one should do after delivering the placenta

during controlled –cord traction?iii. In what situations controlled cord traction is contraindicated?

Homework 5.4

Go to the library and read the book titled ‘A Book for Midwives: Care for pregnancy,

birth, and women’s health’ chapter 12, from page 226 to 230.5.2.5 Delivery of the placenta

Learning Activity 5.2.5

i) What should the nurse do before starting the delivery of the placenta?

ii) What signs should the nurse check to make sure if the placenta hasseparated from the uterine wall?

Before going into the details of placenta delivery, it is essential to understand the

biological events that lead to the delivery of the placenta. The placenta normally

separates with the third or fourth strong uterine contraction after the birth of the

baby. After the birth, the nurse must watch the mother for any signs of infection, preeclampsia,

and heavy bleeding. The nurse has to also check the mother’s blood

pressure and pulse within the 30 minutes after birth.

In spontaneous vaginal birth, the placenta usually separates from the womb in the

first few minutes after birth. However, in some cases it may take some time to come

out. In order to ascertain that the placenta has separated from the uterus, the care

provider has to check the following signs:

• A small gush of blood comes from the vagina. A gush is a handful of blood that

comes out all at one time.

• The cord looks longer because when the placenta comes off the wall of the

uterus, it drops down closer to the vaginal opening which makes the cord

seem a little longer because more of it appears outside the woman’s body.

• Check if the uterus has risen. This should be checked because when the

placenta separates from the uterine wall, the top of the uterus moves a little

below the mother’s navel.

If 30 minutes have elapsed since the birth of baby and there are no signs that the

placenta has separated from the uterus, the care provider should check if the baby

has started breastfeeding. Breastfeeding causes contractions and will help the

uterus push the placenta out. If the placenta does not deliver after breastfeeding,

request the mother to urinate because a full bladder can slow the birth of the

placenta.

If the placenta does not deliver by itself or if the mother is bleeding heavily, the

care provider has to deliver it. The care provider helps the mother sit up or squat

over a bowl. He/she asks her to push when she feels a contraction and the woman

can also try to push between contractions and the placenta will slip out easily. The

membranes (or bag) that holds the waters and the baby should come out with the

placenta.

Steps in delivering the placenta

Attempt delivery of the placenta only when it is fully separated from the uterus to

avoid uterine inversion or pulling off a section of placenta from the wall of the uterus

leaving the remainder attached, thus creating an open bleeding area in the uterine

wall.

The nurse has to check for separation of the placenta from the uterine wall by doing

the following:

• Placing the hand over the uterus through the abdominal wall (inside a folded

sterile towel) to note when the uterus contracts into a hard globular ball which

rises slightly under your hand.

• Requesting the mother to tell you, after the delivery of the baby, when she

next has contractions.

• Noting whether there is a small gush of blood and/or lengthening of the cord.

• Noting the time of the birth of the baby so you know how long you have waited

for separation of the placenta.

• If you are uncertain whether the placenta has actually separated, you may

also follow the cord with your hand in the vagina, up to the cervix, to determine

if the placenta is trapped in the cervical os, or whether the cord disappears

into the uterus.

Some precautions to take when delivering the placenta

♦ When the woman is bleeding a lot and cannot push the placenta out herself,

gently guide the placenta out by the cord.

♦ But, if the woman is not bleeding and there is no any danger for both the

woman and the baby, do not pull on the cord. Since the placenta is still

attached to the uterus, the cord may break or you may pull the woman’s

uterus out which may result in death. Only guide the placenta out by the cord

if you are sure that the placenta has separated.

♦ If any part of the placenta is missing, immediately report this finding to

the attending physician for intervention. Retained placental fragments cancontribute to postpartum haemorrhage or sepsis.

Self-assessment 5.2.5

i) Explain the steps involved in the delivery of the placenta by a nurse/or any

care provider.

ii) What precautions should a nurse take when delivering the placenta?

5.2.6 Uterine massage

Learning Activity 5.2.6

Using different sources of information, answer the following questions:

a) What do you understand by the term uterine massage?

b) When do we need to apply uterine massage of labour?

Introduction to uterine massage

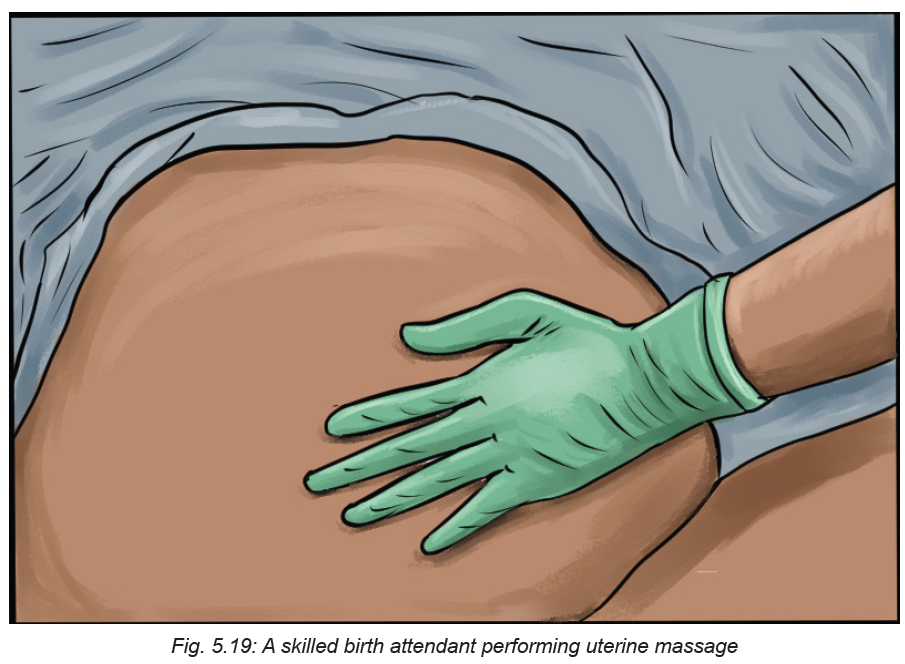

Uterine massage is one of the interventions to manage the third stage of labour

especially after the birth of the baby and after the placenta had been delivered.

Light massage of the abdomen is performed in order to stimulate the uterus contract

in order for it to return to its normal size. The uterine massage is advantageous

because it helps in preventing massive blood loss after childbirth which can lead to

both maternal morbidity and mortality rate.

How long the uterine should be done

Uterine massage should be done immediately after third stage of labour in

spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Techniques of offering uterine massage

• Before performing uterine massage, advise the woman to empty her bladder.

A full bladder may push the uterus off to the side, which makes the massage

process both uncomfortable and ineffective.

• Ask the woman to relax her body as much as possible. The skilled birth

attendant guides the woman to practice deep breathing and muscle relaxation

immediately prior and during the massage. The woman relaxes her muscle

and take slow, calm breaths to help with the potential discomfort.

• The nurse places a hand on the woman’s lower abdomen and stimulates the

uterus by massaging.

• Ask the woman to lie down flat.

Once, she is lying flat on her back, place your flat palms on her abdomen at about

where her belly button is located. If her uterus is hard, you should not need to

massage the area. If the area is soft and you feel little resistance, a massage maybe recommended.

Take one hand and cup it slightly. Slowly move it in a circular motion over the

woman’s lower abdomen. Keep doing these movements until you feel her uterus

contract.

Self-assessment 5.2.6

i. When should we do uterine massage and for how long.

ii. What are the advantages of uterine massage?

iii. Briefly describe the steps involved in offering uterine massage.

iv. What precautions does a nurse should take prior and during uterinemassage?

End unit assessment 5

1. When is the second stage of labour starts and ends?

2. What are the signs indicating that the second stage of labour has begun?

3. What elements of monitoring during the second stage of labour?

4. Explain the following the following terms:

a. Engagement

b. Descent

c. Flexion

d. Internal rotation

e. Extension

f. External rotation

g. Expulsion.

5. Explain in orderly sequence the three processes characterising the third

stage of labour?

6. Why the active management of the third stage of labour is more effective

than the physiological management of the third stage of labour?

7. Which uterotonic drug of choice is used in active management of third

stage of labour?

8. What are the advantages of using uterotonic in third stage of labour?

9. Mention all uterotonic you know that can be used in third stage of labour.

10. What is the importance of delayed cord clamping in third stage of labour?

11. Describe each step involved in cord clamping.

12. What should one avoid while doing controlled cord-traction?

13. What important technique one should do after delivering the placenta

during controlled –cord traction?

14. In what situations controlled cord traction is contraindicated?

15. What should the nurse do before starting the delivery of the placenta?

16. What are the signs of placenta separation during third stage of labour?

17. Describe the steps involved in the delivery of the placenta?

18. What precautions should a nurse take when delivering the placenta?

19. When should we do uterine massage and for how long.

20. What are the advantages of uterine massage?

21. What precautions does a nurse take prior and during uterine massage?

Multiple choice questions

1. What is the drug of choice in active management of third stage management?

a) Intravenous Ergometrine

b) Intramuscular egometrine

c) Intramuscular oxytocin (Pitocin)

d) Misoprostol

2. The following are the causes of prolonged third stage of third stage except

a) Failure of the uterus to contract well

b) Abnormal placenta insertion. e.g. placenta accreta

c) Cord prolapse.

d) Failure of the placenta to separate normally.

3 Which ONE of the following options outlines the causes of postpartum

haemorrhage in third stage of labour?

a) Uterine atony, uterine inversion and Full bladder

b) Not well repaired episiotomy, clitoral tears, recto prolapse

c) Vaginal tears, perennial tears and contracted uterus

d) None of the above.

4. Normal third stage will involve the following stages except

a) placenta separation,

b) placenta descent

c) placenta expulsion

d) placenta insertion

5. Answer the following questions with true or false

a) In active management of third stage of labour oxytocin should be given

immediately after childbirth wit out palpating to find out if there is another

baby.

b) Retained placenta is not a danger sign in third stage of labour.

c) Postpartum haemorrhage is defined as blood loss of 500mls in spontaneous

vaginal delivery and 1000mls in caesarean section.

d) Prolonged third stage is when the placenta fails to separate within 2 hours

after child birth.

e) Full bladder causes postpartum haemorrhage

f) Full bladder causes postpartum haemorrhage.

Controlled cord traction is not contra-indicated before the signs of placenta

separation are noticed.

6. Answer the following questions with true or false

a)In active management of third stage of labour oxytocin should be given

immediately after childbirth wit out palpating to find out if there is another

baby.b)Full bladder causes postpartum haemorrhage.