UNIT8:INTRODUCTION TO PALLIATIVE CARE

Apply the principles of palliative care to alleviate pain, support psychologically and

spiritually the individuals, families and community during life threatening illnessesand during end-of-life period

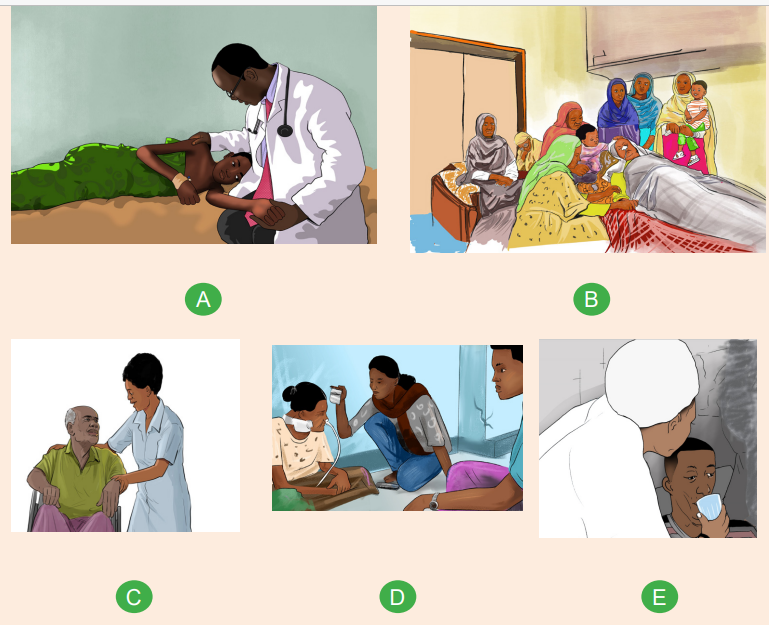

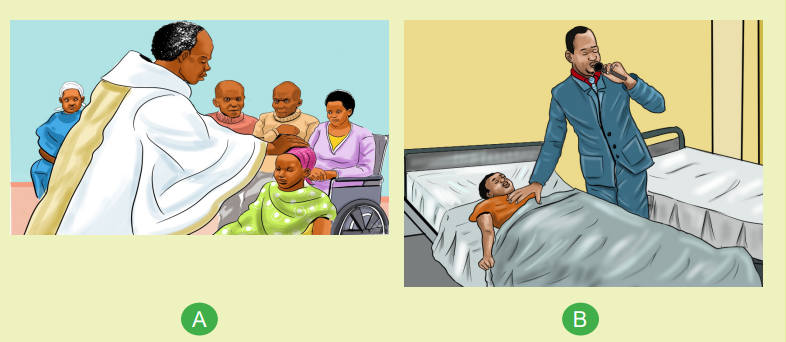

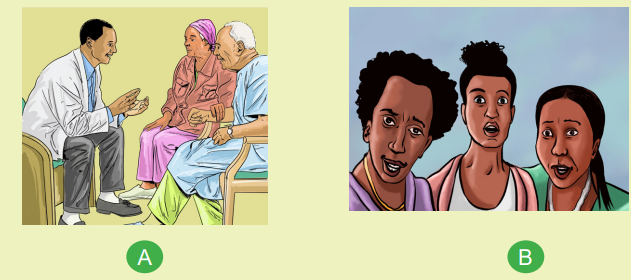

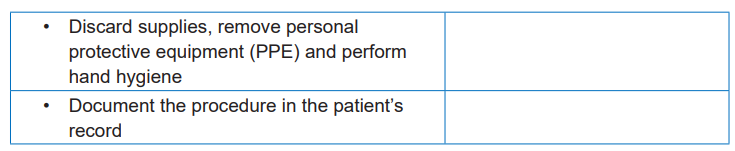

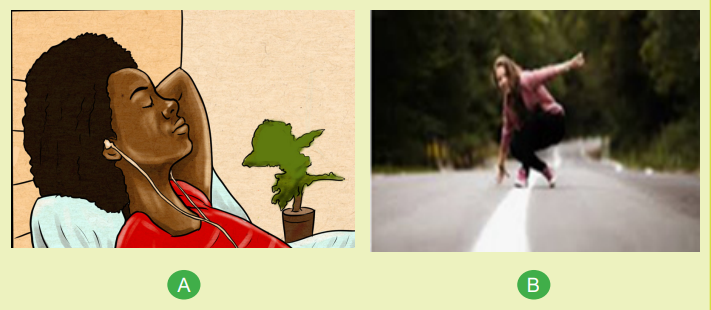

Introductory activity 8

1) What do the pictures A, B, C, D, and E have in common?

2) What do you think is the focus of this unit 8?

Definition:

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined Palliative care “as an approach

to care which improves quality of life of patients and their families facing life

threatening illness, through the prevention, assessment and treatment of pain and

other physical, psychological and spiritual problems.”

The primary goal of palliative care:

It is to help patients and families achieve the best possible quality of life.

The goals of palliative care:

For patients with active, progressive, far-advanced disease, the goals of palliative

care are

• To provide relief from pain and other physical symptoms

• To maximize the quality of life

• To provide psychosocial and spiritual care

• To provide support to help the family during the patient’s illness and

bereavement

Scope of palliative care:

Although it is especially important in advanced or chronic illness, it is appropriate

for patients of any age, with any diagnosis, at any time, or in any setting.

Patients who have complex serious illnesses often benefit from palliative care

throughout the course of their illness, even while seeking treatment for their disease.

As the goals of care change and cure for illnesses becomes less likely, the focus

shifts to more palliative care strategies. Palliative care interventions are not only

appropriate at the end of life. Making this distinction is important because some

patients, family members, or health care professionals refuse helpful palliative careinterventions, believing that palliative care is only for the dying.

to care which improves quality of life of patients and their families facing life

threatening illness, through the prevention, assessment and treatment of pain and

other physical, psychological and spiritual problems.”

The primary goal of palliative care:

It is to help patients and families achieve the best possible quality of life.

The goals of palliative care:

For patients with active, progressive, far-advanced disease, the goals of palliative

care are

• To provide relief from pain and other physical symptoms

• To maximize the quality of life

• To provide psychosocial and spiritual care

• To provide support to help the family during the patient’s illness and

bereavement

Scope of palliative care:

Although it is especially important in advanced or chronic illness, it is appropriate

for patients of any age, with any diagnosis, at any time, or in any setting.

Patients who have complex serious illnesses often benefit from palliative care

throughout the course of their illness, even while seeking treatment for their disease.

As the goals of care change and cure for illnesses becomes less likely, the focus

shifts to more palliative care strategies. Palliative care interventions are not only

appropriate at the end of life. Making this distinction is important because some

patients, family members, or health care professionals refuse helpful palliative careinterventions, believing that palliative care is only for the dying.

8.1. Historical background of palliative care

Self-assessment 8.1

1) Shortly explain at least 4 timeline of important events in the history of

palliative care

At the end of the Second World War in 1945, people in Western societies were tired

of death, pain, and suffering. Cultural goals shifted away from war-centered activities

to a focus on progress, use of technology for better living, and improvements in

the health and well-being of the public. Guided by new scientific knowledge and

new technologies, health care services became diversified and specialized andlifesaving at all costs became a powerful driving force.

End-of-life care was limited to postmortem rituals, and the actual caregiving of

dying patients was left to nursing staff. Palliative nursing in those days depended

on the good will and personal skills of individual nurses, yet what they offered was

invisible, unrecognized, and unrewarded.

Thanks to the efforts of many people across the years, end-of-life care is

acknowledged today as an important component of integrated health care services.

Much knowledge has accrued about what makes for good palliative care, and

nurses have been in the forefront of efforts to improve quality of life for patients and

families throughout the experience of illness.

The nurse gives attention to the physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and

existential aspects of the patient and family—whole person care.Below is a brief timeline of important events in the history of palliative care:

• 1967: Palliative care was born out of the hospice movement. Dame

Cicely Saunders is widely regarded as the founder of the hospice movement.

She had degrees in nursing, social work, and medicine. She introduced

the idea of “total pain,” which included the physical, emotional, social, and

spiritual dimensions of distress. Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice

in London in 1967.

• 1969: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published her book On Death and Dying. In

this book, she defined the five stages of grief through which many terminally

ill patients progress: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Although we now believe dying patients do not necessarily go through these

phases and that these phases do not necessarily occur in a set order, Kübler

Ross’s book and lectures raised public consciousness about care for patients

at the end of life.

• 1974: Florence Wald, the dean of Yale School of Nursing, was so inspired by

a lecture by Dr. Saunders at Yale that she went to visit St. Christopher’s in

1969. Florence Wald then founded the first hospice in the United States, in

Branford, Connecticut, in 1974. At the start of the hospice movement in the

United States, most hospices were home based and volunteer led.

• 1974: Dr. Balfour Mount, a surgical oncologist from McGill University, coined

the term “palliative care” to distinguish it from hospice care. While hospice

falls under the umbrella of palliative care, palliative care can be provided from

the time of diagnosis of a serious illness and concurrently with curative or life

prolonging treatment.

• 1990: The World Health Organization recognized palliative care as a

distinct specialty dedicated to relieving suffering and improving quality of life

for patients with life-limiting illness.

• 1997: The Institute of Medicine report “Approaching Death: Improving

Care at the End of Life” noted discrepancies between what the American public

wanted for end-of-life care and how Americans were experiencing end of life

in the United States. With tremendous support from multiple philanthropic

foundations, multifaceted efforts were made to promote palliative care.

• 2006: The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognized

hospice and palliative care as its own specialty.

• 2010: The New England Journal of Medicine published a study by Dr.

Jennifer Temel and colleagues that showed that people with lung cancer

who received early palliative care in addition to standard oncologic care

experienced less depression and increased quality of life and survived 2.7months longer than those receiving standard oncologic care.

Self-assessment 8.1

1) What did world Health Organization do in 1990 as regards to palliative

care?

2) What are the five stages of grief according to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross 1969

book on death and dying?

3) How did Dr. Balfour Mount distinguish hospice care from palliative carein1974?

8.2. Components of palliative care

Learning activity 8.2

Use the following link and watch the video on palliative care: https://www.youtube.

com/watch?v=TZCI25C8tEQ

With use of student text book of fundamentals of nursing or any relevant book,

discusses the components of palliative care

Palliative care incorporates the whole spectrum of care—medical, nursing,

psychological, social, cultural and spiritual. A holistic approach, incorporating these

wider aspects of care is essential in palliative care.

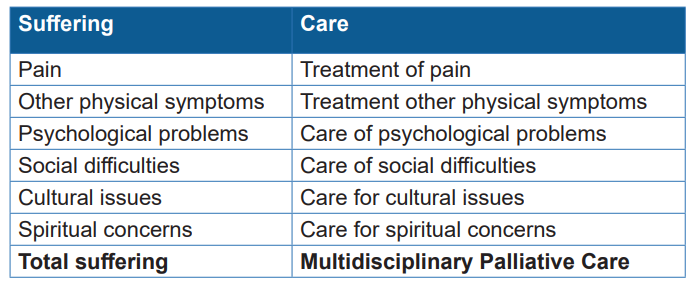

The following table illustrates the components of palliative care, or the aspects of

care and treatment that need to be addressed, follow logically from the causes of

suffering. Each has to be addressed in the provision of comprehensive palliativecare, making a multidisciplinary approach to care a necessity.

Treatment of pain and physical symptoms are addressed first because it is not

possible to deal with the psychosocial aspects of care if the patient has unrelieved

pain or other distressing physical symptoms.

The various causes of suffering are interdependent and unrecognized or

unresolved problems relating to one cause may cause or exacerbate other aspects

of suffering.

Unrelieved pain can cause or aggravate psychosocial problems. These psychosocial

components of suffering will not be treated successfully until the pain is relieved.

Pain may be aggravated by unrecognized or untreated psychosocial problems.

No amount of well prescribed analgesia will relieve the patient’s pain until the

psychosocial problems are addressed.

Palliative care nursing reflects a “whole-person” philosophy of care implemented

across the lifespan and across diverse health care settings.

Relieving suffering and enhancing quality of life include the following: providing

effective pain and symptom management; addressing psychosocial and spiritual

needs of the patient and family; incorporating cultural values and attitudes into the

plan of care; supporting those who are experiencing loss, grief, and bereavement;

promoting ethical and legal decision-making; advocating for personal wishes and

preferences; using therapeutic communication skills; and facilitating collaborative

practice.

In addition, in palliative nursing, the “individual” is recognized as a very important

part of the healing relationship. The nurse’s individual relationship with the patient

and family is seen as crucial. This relationship, together with knowledge and skills,

is the essence of palliative care nursing and sets it apart from other areas of nursing

practice.

Palliative care as a therapeutic approach is appropriate for all nurses to practice. It

is an integral part of many nurses’ daily practice, as is clearly demonstrated in work

with the elderly, the neurologically impaired, and infants in the neonatal intensivecare unit.

The palliative care nurse frequently cares for patients experiencing major

stressors, whether physical, psychological, social, spiritual, or existential.

Many of these patients recognize themselves as dying and struggle with this role.

To be dying and to care for someone who is dying are two sides of a complex social

phenomenon. There are roles and obligations for each person. To be labeled as“dying” affects how

Self-assessment 8.2

1) Identify the aspects of care and treatment that need to be addressed in

palliative care2) Explain how the various causes of suffering are interdependent

8.3. Principles of palliative care

Learning activity 8.3

Use the following link and watch the video on palliative care: https://www.youtube.

com/watch?v=TZCI25C8tEQ

With use of student text book of fundamentals of nursing or any relevant book,

discusses the principles of palliative care

The following principles have been informed by research-based evidence:

• A caring attitude

• Consideration of individuality

• Care is patient, family and carer centered

• Care provided is based on assessed need

• Cultural considerations: linking the principles of ethics, humanities, and

human values into every patient- and family-care experience

• Consent

• Choice of site of care

• Effective communication

• Clinical context: Appropriate treatment

• Comprehensive inter-professional care / Multidisciplinary care

• Care excellence

• Consistent medical care

• Coordinated care

• Care should be integrated

• Continuity of care

• Crisis prevention

• Caregiver support

• Continued reassessment

• Advance Care Planning

• Patients, families and carers have access to local and networked services to

meet their needs

• Care is evidence-based, clinically and culturally safe and effective

• Care is equitable

• Scope of care

• Timing of palliative care

• Holistic care

Here below, each of the principles of palliative care is explained:

A caring attitude:

It involves sensitivity, empathy and compassion, and demonstrates concern for the

individual. There is concern for all aspects of a patient’s suffering, not just the medical

problems. There is a non-judgmental approach in which personality, intellect, ethnic

origin, religious belief or any other individual factors do not prejudice the delivery of

optimal care.

Consideration of individuality:

There are psychosocial features and problems that make every patient a unique

individual. These unique characteristics can greatly influence suffering and need to

be taken into account when planning the palliative care for individual patients.

Care is patient, family and career centered:

Patient, family and carer centered care requires that they be actively involved in all

aspects of care, including care planning and setting holistic goals of care. Patients,

families and careers are ‘partners’ in the decision making regarding the provision

of their healthcare. This results in care that aims to ensure ‘patients receive

comprehensive health care that meets their individual needs, and considers the

impact of their health issues on their life and wellbeing. It also aims to ensure that

risks of harm for patients during health care are prevented and managed through

targeted strategies. Comprehensive care is the coordinated delivery of the total

health care required or requested by a patient. This care is aligned with the patient’s

expressed goals of care and healthcare needs, considers the impact of the patient’shealth issues on their life and wellbeing, and is clinically appropriate

Patient, family and carer centered care is an historical cornerstone of end of life

and palliative care. When patients, families and carers are supported by the health

system to actively participate, research has shown that it can lead to increased

patients’ satisfaction with health care services, improved patients’ self-perceptions,

reduced stress and increased empowerment.

Care provided is based on assessed need:

Making care available on the basis of assessed need ensures that every patient,

family and carer gets access to care that is individualised based on their goals,

wishes and circumstances.

A key learning from consultations is that “people’s needs change.” The needs of

the patient, family and carer will vary with time and across care settings during their

palliative and end of life journey.

Needs-based care requires services be available with skilled staff to meet

the needs of patients, families and carers. Regular assessment of need allows

patients, families and carers to describe their changing needs over time and helps

services be responsive, coordinated and flexible in meeting these changing needs

including reassessing care plans and goals of care. Needs-based assessment

drives effective referral and clinical handover therefore, clinical staff must have the

skills to undertake holistic needs assessments as people in their care approach

and reach the end of life helping to ensure that people get the right care in the right

place at the right time.

Cultural considerations: linking the principles of ethics, humanities, and

human values into every patient- and family-care experience:

Ethnic, racial, religious and other cultural factors may have a profound effect on a

patient’s suffering. Cultural differences are to be respected and treatment planned

in a culturally sensitive manner.

Good palliative care is significant in the manner, in which it embraces cultural, ethnic,

and faith differences and preferences, while interweaving the principles of ethics,

humanities, and human values into every patient- and family-care experience

Consent:

The consent of a patient, or those to whom the responsibility is delegated, is

necessary before any treatment is given or withdrawn. In most instances, adequately

informed patients will accept the recommendations made

Choice of site of care:

The patient and family need to be included in any discussion about the site (place/

setting) of care.

The patients with a terminal illness should be managed at home whenever possible.

Effective communication:

Good communication between all the health care professionals involved in a

patient’s care is essential and is fundamental to many aspects of palliative care.

Good communication with patients and families is also essential. Healthcare

providers should develop communication skills including listening, providing

information, facilitating decision making and coordinating care.

Important and potentially difficult discussions are frequently necessary with palliative

care patients, who have active, progressive, far-advanced disease, regarding:

• Breaking bad news

• Further treatment directed at the underlying disease

• Communicating prognoses

• Admission to a palliative care program

• Artificial nutrition

• Artificial hydration

• Medications such as antibiotics

• Do-not-resuscitate orders

• Decisions must be individualized for each patient and should be made in

discussion with the patient and family.

Clinical context: Appropriate treatment:

All palliative treatment should be appropriate to the stage of the patient’s disease and

the prognosis. Over-enthusiastic therapy that is inappropriate and patient neglect

are equally deplorable. Care must be taken to balance technical interventions

with a humanistic orientation to dying patients. The prescription of appropriate

treatment is particularly important in palliative care because of the unnecessary

additional suffering that may be caused by inappropriately active therapy or by lack

of treatment.

When palliative care includes active therapy for the underlying disease, limits should

be observed, appropriate to the patient’s condition and prognosis. Treatment known

to be useless, given because you have to do something’, is unethical.

Where only symptomatic and supportive palliative measures are employed, all

efforts are directed at the relief of suffering and the quality of life, and not necessarily

at the prolongation of life.

Comprehensive inter-professional care / Multidisciplinary care:

The provision of total or comprehensive care for all aspects of a patient’s suffering

requires an interdisciplinary team.

A multidisciplinary team approach is essential to address all relevant areas of

patient care. In order to facilitate a family in crisis to establish and then achieve

mutually agreed upon goals, the palliative care team integrates and coordinates the

assessment and interventions of each team member and creates a comprehensive

plan of care.

A multidisciplinary approach to assessment and treatment is mandatory. Failure to

do this often results in unrelieved pain and unrelieved psychosocial suffering.

Successful palliative care requires attention to all aspects of a patient’s suffering,

which requires input or assistance from a range of medical, nursing and allied

health personnel—a multidisciplinary approach. Established palliative care

services work as a multidisciplinary or inter-professional team.

Multidisciplinary is the term that used to be applied to palliative care teams, but if

the individuals work independently and there are no regular team meetings, patient

care may become fragmented and conflicting information given to patients and

families.

Inter-professional is the term now used for teams that meet on a regular basis to

discuss patient care and develop a unified plan of management for each patient,

and provide support for other members of the team.

Where palliative care services have not yet been established, it is important for

the few professionals providing such care to work as a team, meeting regularly,

planning and reviewing care, and supporting each other.

The patient may be considered a ‘member’ of the team (although they do not

participate in team meetings), as all treatment must be with their consent and in

accordance with their wishes.

The members of the patient’s family can be considered ‘members’, as they have

an important role in the patient’s overall care and their opinions should be included

when formulating a plan of management.

The ideal multidisciplinary team involves:

• Medical staff,

• Nursing staff,

• Social worker

• Physiotherapist

• Occupational therapist

• Dietician

• Psychologist (or liaison psychiatrist)

• Chaplain (or pastoral care worker)

• Volunteers

• Other personnel, as required

• Family members

• Patient

Volunteers play an important role in many palliative care services

Care excellence:

Palliative care should deliver the best possible medical, nursing and allied health

care that is available and appropriate.

Palliative care is active care and requires specific management for specific

conditions. It requires health care providers equipped with quality knowledge and

skills.

Consistent medical care:

Consistent medical management requires that an overall plan of care be established,

and regularly reviewed, for each patient. This will reduce the likelihood of sudden or

unexpected alterations, which can be distressing for the patient and family.

Coordinated care:

It involves the effective organization of the work of the members of the inter

professional team, to provide maximal support and care to the patient and family.

Care planning meetings, to which all members of the team can contribute, and at

which the views of the patient and the family are presented, are used to develop a

plan of care for each individual patient.

Care should be integrated:

Integration of care is an approach that aims to deliver seamless care within the

health system and its interface with social care. It laces people at the centre of care,

providing comprehensive wrap around support for individuals with complex needs

and enabling individuals to access care when and where they need it.

Palliative care is integral to all healthcare settings (hospital, emergency department,

health clinics and homecare).

A more integrated healthcare system is easy to use, navigate and access. It is

responsive to the specific health needs of local communities, providing them with

more choice and greater opportunities to actively engage with the health system.

For service providers and clinicians, integrating care supports them to collaborate

more effectively across health and with social care.

Healthcare providers and patients, families and carers at times describe health

services as being siloed / isolated in their care and in the systems they use to

support that care. This results in care that is delayed and or fragmented and not

supported with timely, transferable data that works across agencies and jurisdictions.

Integrating care is vital to improving outcomes for vulnerable and at-risk populations

and people with complex health and social needs.

Continuity of care:

The provision of continuous symptomatic and supportive care from the time the

patient is first referred until death is basic to the aims of palliative care. Problems

most frequently arise when patients are moved from one place of care to another

and ensuring continuity of all aspects of care is most important.

Crisis prevention:

Good palliative care involves careful planning to prevent the physical and emotional

crises that occur with progressive disease. Many of the clinical problems can be

anticipated and some can be prevented by appropriate management. Patients and

their families should be forewarned of likely problems, and contingency plans made

to minimize physical and emotional distress

Caregiver support:

The relatives of patients with advanced disease are subject to considerable

emotional and physical distress, especially if the patient is being managed at home.

Particular attention must be paid to their needs as the success or failure of palliative

care may depend on the caregivers’ ability to cope

Continued reassessment:

This is a necessity for all patients with advanced disease for whom increasing and

new clinical problems are to be expected. This applies as much to psychosocial

issues as it does to pain and other physical symptoms.

Advance Care Planning:

Advance care planning is a means for patients to record their end-of-life values

and preferences, including their wishes regarding future treatments (or avoidance

of them)

Advance care planning involves a number of processes:

• Informing the patient

• Eliciting preferences

• Identifying a surrogate decision maker to act if the patient is no longer able to

make decisions about their own care

It involves discussions with family members, or at least with the person who is to be

the surrogate decision maker.

The principle of advance care planning is not new. It is common for patients aware

of approaching death to discuss with their carers how they wish to be treated.

However, these wishes have not always been respected, especially if the patient

is urgently taken to hospital and if there is disagreement amongst family members

about what is appropriate treatment. There is less conflict between patients and

their families if advance care planning has been discussed.

Patients, families and carers have access to local and networked services to meet

their needs

Providing care as close to home as possible means that people have access

to high quality, services and supports required to meet their needs, wishes and

circumstances. Home can include a residential aged care facility or a relative’s

home.

Decisions about how close to home it is possible to provide care will start with a

detailed understanding of the patient, family and carer wishes combined with good

clinical judgement and decision-making about safe and practical options. As always

in a patient-centred model of care these options need to be negotiated and agreed

with the patient, family and carer.

Care is evidence-based, clinically and culturally safe and effective

This means that: people receive health care without experiencing preventable harm.

People receive appropriate evidence-based care. There are effective partnerships

between consumers and healthcare providers and organizations at all levels of

healthcare provision, planning and evaluation. Ensuring clinical, cultural and

psychological safety means patients; families and carers experience no negative

consequences.

All people in need should have equitable access to quality care based on assessed

need as they approach and reach the end of life. Ensuring that care provided is in

accordance with best practice recommendations, is organized for quality and is

driven by the collection and reflection of appropriate and meaningful clinical data

are all necessary components of quality systems. Quality and safety in palliative and

end of life care is eroded when there are gaps in resourcing and support available

to those providing such care.

Care is equitable:

We know that some population groups and clinical cohorts do not have equitable

access to care or experience care that is sub-optimal and or culturally unsafe or

inappropriate.

Equity in relation to health care means that patients, families and carers have equal

access to available care for equal need; equal utilization for equal need and equal

quality of care for all.

Evidence shows that care to people approaching and reaching the end of life is

often fragmented and under-utilized by identified population groups or clinical

cohorts. These included Aboriginal people, people under the age of 65, people who

live alone, and people of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, people

with a non-cancer diagnosis, people living with dementia and people living with a

disability.

There is a growing body of evidence indicating that given a choice, patients would

prefer to die at home or as close to home as possible. However, a lack of services

to support that care means that many people die in acute care settings or for people

in rural and remote areas, death occurs far from their local community. A lack of

after-hour support services particularly inhibits carers and family members’ ability

to provide home care.

The next text discusses the principles of palliative care management:

Scope of care:

It includes patients of all ages with life-threatening illness, conditions or injury

requiring symptom relief from physical, psychosocial and spiritual suffering.

Timing of palliative care:

Palliative care should ideally begin at the time of diagnosis of a life threatening

condition and should continue through treatment until death and into the family’s

bereavement.

Holistic care:

Palliative care must endeavor to alleviate suffering in the physical, psychological,

social and spiritual domains of the patient in order to provide the best quality of lifefor the patient and family

Self-assessment 8.3

Explain the following principles of palliative care:

1) Care is integrated and coordinated

2) Care is equitable

3) Holistic care

4) Multidisciplinary care5) Effective communication

8.4. Non-pharmacological Pain management techniques

Learning activity 8.4

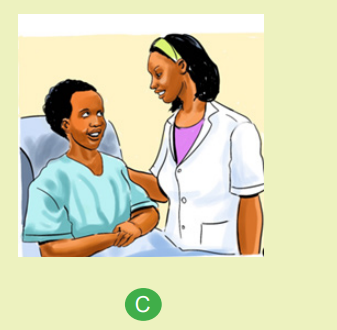

Observe the pictures below and answer the asked questions:

1) What are you seeing on the image above?

2) Describe the importance of this action on patient pain

8.4.1. Advantages and disadvantages of non-pharmacologicalinterventions

Non-pharmacological pain managements are ways to decrease pain without

medicine. Non-pharmacological pain management interventions are a set of

psychological and physical pain management methods that play a vital role and

can be used both complementarily and independently

a. Advantages of non-pharmacological interventions

Non pharmacological interventions lower medical costs, greater availability to

patients, diversification and ease of use and greater patient satisfaction. They also

reduce the likelihood of dependence on drug interventions by facilitating pain relief

as the first line of treatment.

b. Disadvantages

Disadvantage of non-pharmacological pain management include time consuming,

may request advanced technology such as network in case of video, need the

patient cooperation and understanding its benefits for both nurses and patients in

order to be a successful method.

8.4.2. Non-pharmacological pain management approaches

Non-pharmacological approaches to the relief of pain may be classified as follows1)

psychological interventions, (2) acupuncture and acupressure, (3) transcutaneous

electrical nerve stimulation, (4) physical therapies

a. Psychological interventions

Psychological interventions include distraction, stress management, hypnosis,

and other cognitive-behavioral interventions. For patients dealing with chronic pain,

psychological interventions plans are designed often involves teaching relaxation

techniques, changing old beliefs about pain, building new coping skills and

addressing anxiety or depression that may accompany pain.

b. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

TENS is a therapy that uses low voltage electrical current to provide pain relief. A

TENS unit consists of a battery-powered device that delivers electrical impulses

through electrodes placed on the surface of your skin.

c. Acupuncture and acupressure

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese technique that involves the insertion of

extremely fine needles into the skin at specific called acupoints. This may relieve

pain by releasing endorphins, the body’s natural pain-killing chemicals, and by

affecting the part of the brain that governs serotonin, a brain chemical involved with

mood.

Acupressure is a traditional Chinese medicine therapy in which pressure is applied

to a specific point on the body. It is done to free up energy blockages said to cause

health concerns from insomnia to menstrual cramps.

d. Physical therapies

Physical therapies include massage, heat and cold application, physiotherapy,

osteopathy ( a system of complementary medicine involving the treatment of medical

disorders through the manipulation and massage of the skeleton and musculature.

osteopath aims to restore the normal function and stability of the joints to help the

body heal itself.) and chiropractic which is a healthcare profession technic that

cares for a patient’s neuromusculoskeletal system like the bones, nerves, muscles,

tendons, and ligaments. A chiropractor helps manage back and neck pain throughthe use of spinal adjustments to maintain good alignment.

Self-assessment 8.4

1) What is non-pharmacological pain management?

2) Differentiate osteopath and chiropractic

3) What are advantages and disadvantages of non-pharmacological painmanagement

8.5. Additional methods of non-pharmacological painmanagement

Learning activity 8.5

Observe the following picture and answer the questions below:

1) What are you seeing on the image above?

2) Describe the importance of the video images on this patient condition

Relaxation Techniques for non-pharmacological pain management

Relaxation exercises calm the mind, lower the amount of stress hormones in the

blood, relax muscles, and elevate the sense of well-being. Using them regularly can

lead to long term changes in the body to counteract the harmful effects of stress.

There is no best relaxation technique for natural pain relief. Just choose whatever

relaxes you, like music, prayer, gardening, going for a walk, or talking with a friend

on the phone. Relaxation techniques can include:

• Aromatherapy is a way of using scents to relax, relieve stress, and decrease

pain. Aromatherapy uses oils, extracts, or fragrances from flowers, herbs, and

trees. They may be inhaled or used during massages, facials, body wraps,

and baths.

• Foursquare breathing. Breathe deeply so that your abdomen expands and

contracts like a balloon with each breath. Inhale to a count of four, hold for a

count of four, exhale to a count of four, then hold to a count of four. Repeat

for ten cycles.

• Tense your muscles and then relax them. Start with the muscles in your

feet then slowly move up your leg. Then move to the muscles of your middlebody, arms, neck and head

• Meditation and yoga may help your mind and body relaxes. They can also

help you have an increased feeling of wellness. Meditation and yoga help you

take the focus off your pain.

• Guided imagery teaches you to imagine a picture in your mind. You learn to

focus on the picture instead of your pain. It may help you learn how to change

the way your body senses and responds to pain.

• Music may help increase energy levels and improve your mood. It may help

reduce pain by triggering your body to release endorphins. These are natural

body chemicals that decrease pain. Music may be used with any of the other

techniques, such as relaxation and distraction.

• Heat helps decrease pain and muscle spasms. Apply heat to the area for 20

to 30 minutes every 2 hours for as many days as directed. Remember to be

cautious in order to avoid to burn the patient

• Ice helps decrease swelling and pain. Ice may also help prevent tissue

damage. Use an ice pack, or put crushed ice in a plastic bag. Cover it with a

towel and place it on the area for 15 to 20 minutes every hour, or as directed.

• Massage therapy may help relax tight muscles and decrease pain.

• Physical therapy teaches you exercises to help improve movement and

strength, and to decrease pain.

• Comfort therapy: Comfort therapy may involve companionship, exercise,

heat/cold application, lotions/massage therapy, meditation, music, art, or

drama therapy, pastoral counseling and positioning.

• Physical and occupational therapy: Physical and occupational therapy

may involve aquatherapy, tone and strengthening and desensitization

• Psychosocial therapy/counseling: Psychosocial therapy/counseling may

involve individual counseling, family counseling and group counseling

• Neurostimulation: Neurostimulation may involve Transcutaneous electricalnerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture and acupressure.

Self-assessment 8.5

1) What is non -pharmacological pain management?

2) Outline three examples non pharmacological pain management3) What is the best relaxation techniques in pain management?

8.6. Pain evaluation in palliative care

Learning activity 8.6

Watch this picture provide the answers to the questions presented below it:

The above patient is hospitalized in a district hospital and he was diagnosed with

pancreatic cancer at advanced stage. He is experiencing irresistible pain, crying

for help. You give painkiller and after 1 hour he told you that he still experiences

pain and requests additional painkiller.

1) How are you going proceed in managing this patient?

2) What are possible complications that can arise if the pain is not treated?

The pain evaluation should encompass physical, psychological, social and spiritual

components as they all interact upon one another. Untreated chronic pain can cause

different complications including decreased mobility, decreased concentration,

depression, anorexia, sleep disturbances and impaired immunity with all associated

complications that can arise from impaired immune system. Adequate management

of pain will alleviate the complications of pain.

Pain causes distress and suffering for people and their loved ones. Pain can also

increase blood pressure and heart rate, and can negatively affect healing. Pain

keeps people from doing things they enjoy. It can prevent them from talking and

spending time with others. It can affect their mood and their ability to think. Managing

the pain is very important as it helps ease suffering, improving patient comfort and

therefore patient satisfaction. Pain control can facilitate early ambulation, adequate

oxygenation and nutrition and reduce the stress. This helps the speed up the

recovery time and may reduce the risk of developing depression.

The first principle of managing pain is an adequate and full assessment of where

the underlying pain is coming from. Patients may have more than one area of pain

and different pains have different causes. The acronym SOCRATES is used toassess pain:

• Site: Where is the pain? The maximal site of the pain.

• Onset: When did the pain start, and was it sudden or gradual? Include also

whether it is progressive or regressive.

• Character: What is the pain like? An ache? Stabbing?

• Radiation: Does the pain radiate anywhere?

• Associations: Any other signs or symptoms associated with the pain?

• Time course: Does the pain follow any pattern?

• Exacerbating/relieving factors: Does anything change the pain?• Severity: How bad is the pain?

Self-assessment 8.6

1) Using SOCRATES, describe how you can assess pain

2) What is importance of managing of patient pain?3) What are complications associated with pain?

8.7. Psychosocial support

Learning activity 8.7

Mr. F aged 35 is a married with 3 children. The first born is 6 years old; the

second is 4 years old while the last is one year old. He is the chief of his family

and he was working to satisfy his family’s basic needs, his wife is a nurse at

one District hospital. Mr. F has been informed that he has stage IV Metastatic

Melanoma since 6 months ago. He has been receiving chemotherapy over the

duration of his illness. Chemotherapy can cause side effects such as nausea,

vomiting depression, tiredness and thinning or loss of hair. His family cared for

him at home until two weeks ago. He has now moved to a hospice for respite

care. Mr. is a pastor in one protestant church and therefore he receives many

visitors.

1) What do you think could be the psychological impacts of Mr. F’s disease?

2) If you are nurse caring M.r F what do you think as nursing actions that

could help Mr.F alleviate his discomfort other than medication.

End of life is a difficult time for patients and their relatives and careers. It is important

that psychosocial care is provided to palliative patients and their families in various

ways through a range of medical, nursing and allied healthcare professionals. It is

imperative for nurses in palliative care to know about any specific cultural practices,

spiritual and psychosocial conditions of the patients.

The term psychosocial denotes both the psychological, spiritual and social aspects

of a person’s life and may describe the way people make sense of the world.

Psychological characteristics include emotions, thoughts, attitudes, motivation, and

behavior, while social aspects denote the way in which a person relates to and

interacts with their environment.

Psychosocial support is care concerned with the psychological and emotional well

being of the patient and their family or careers, including issues of self-esteem,

insight into an adaptation to the illness and its consequences, communication,

social functioning and relationships. It is a form of care that encourages patients

to express their feelings about the disease while at the same time providing ways

by which the psychological and emotional well-being of such patients and their

caregivers are improved.

In most cases, palliative patients have severe functional and cognitive limitations

requiring support in basic needs, such as hygiene, food, money, medication and

mobility, relying on others for daily life activities, with increasing dysfunction andpsychological repercussions.

8.7.1. Consequences of diagnosis

The psychological and social consequences of a diagnosis of life-limiting illness on

the patient need to be considered. A diagnosis of this kind may provoke a range of

emotional responses in the patient or family member. These include:

• Fear of physical deterioration/ dying; pain/suffering; losing independence; the

consequences of illness or death on loved ones

• Anger at what has happened or what may have caused/ allowed it to happen;

unsuccessful treatment Sadness at approaching the end of life; restriction of

activities due to illness

• Guilt/regret for actions; in some cases for contributing to the development of

the illness

• Changes in sense of identity, adjusting to thinking of themselves as unwell/

dependent

• Loss of self-confidence, sometimes related to loss of physical functioning/

changes in appearance Confusion about what has happened; the future andchoices available.

8.7.2. Importance of psychosocial support

Psychosocial support is very important for patients in palliative care by reducing

both psychological distress and physical symptoms through increasing quality of

life, enhancing coping and reducing levels of pain and nausea with a consequentreduction on demands for hospital resources.

8.7.3. Components of psychosocial support

Psychosocial support and services may include any or all of the following:

• Emotional support, including social activities, companionship and befriending

• Personal care, help with bathing or providing massage and other

complementary therapies

• Assistance in securing financial support

• Help inside and outside the home; for example, cleaning and shopping

• Supplying practical aids such as wheelchairs and other equipment

• Offering counseling and psychological support to help people come to terms

with dying religious/spiritual support, whatever a person’s beliefs

• Practical support in preparing for death, including saying farewell, makingend-of-life decisions and arranging funerals.

8.7.4. Features of psychosocial care

The care taken to address the psychological and social concerns of patients in

palliative care might involve:

Communication

Good communication is at the core of positive end of life experiences. Communication

underpins every aspect of care and is a conduit to psychosocial aspects of care.

Unmet communication needs of people with life limiting illnesses and of carers

can undermine the coordination of care and compromise the provision of relevant

information and subsequent decision-making.

Effective communication and meaningful ongoing conversations during care can

help facilitate knowledge about the palliative patients, their life experiences and

needs of care. Through this increased understanding of the person, it assists in

identifying any emotional, or spiritual concerns they may have which in turn can

improve physical and emotional wellbeing.

Allowing adequate time for communication to occur improves the quality of the

interaction with the person, with research showing a reduction in care time is

achieved due to greater engagement, cooperation and a reduction in distress.

Conversely, poor communication can lead to poor understanding of a person’s

concerns which has a known association with the development of depression and

anxiety.

From the perspective of the family of the person receiving palliative care, their

information needs are critical. Families often wish to be kept informed of their

relative’s condition and value open and timely communication from staff. Deficiencies

in conversations, particularly around changes in their relative’s health status, often

result in family members experiencing feelings of abandonment, anxiety, distress

and fear of the unknown. Fully engaging family members in information sharing

and decision making with honest, open communication can allow them to make

decisions around how best to spend their remaining time with their family member.

Other features:

• Helping patients understand their illness and/or symptoms

• Helping patients to understand their options and plan for the future

• Advocating on behalf of patients/those close to them to ensure they have

access to the best level of care and services available

• Enabling patients and those close to them to express their feelings and

worries related to the illness, listening and showing empathy, providing

comfort through touch as/ when it is appropriate, e.g. holding a patient’s hand

or putting a hand on his or her shoulder. Also, complementary therapies such

as massage

• Helping the patient or family member access any financial aid they may

be entitled to (including benefits, but also charitable trusts/grants where

applicable)

• Practical help with daily activities like grocery shopping

• Arranging personal/social care and organising aids for daily living — setting

up a care package, installing hand rails or other adaptations

• Career support such as making arrangements for respite

• Signposting the patient/those close to them to relevant resources like local

support groups

• Exploring spiritual issues and ensuring the patient is able to continue his or

her religious practices

• Referring the patient or family member to specialist psychological/socialsupport where appropriate

Self-assessment 8.7

1) Psychosocial support is defined as….

a. Means actions that address both the psychological and social needs of

individuals, families and communities

b. Means interventions aimed at curing mental health problems

c. Aims to enhance the self-promoted recovery and resilience of the affected

individual, group and community

d. Means interventions offered to the cadaver after death

2) What are the consequences of deficiency communication to the family

which has a patient under palliative care?

3) Explain the importance of psychosocial support

4) Enumerate three consequences resulting from emotion to palliativepatient or his/her family

8.8. Spiritual support

Learning activity 8.8

Observe the image below and answer the following questions

1) What do you see on the above picture?

2) Describe the importance of the actions which are being done on the

above picture

It is very crucial for nurses in palliative care to know about any specific cultural

practices, spiritual and religious conditions of the patients. Spiritual variables havean important effect mediating physical symptoms and suffering.

8.8.1. Importance of spiritual support in palliative care

Spiritual care has positive effects on individuals’ stress responses, spiritual well

being (such as the balance between physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects

of self), sense of integrity and excellence, and interpersonal relationships. Spiritual

care improves people’s spiritual well-being and performance as well as the quality

of their spiritual life.

spiritual status of patient impact the patient decision-making at the end-of-life and

high levels of spiritual wellbeing have been associated with improved quality of life,

improved coping with disease, improved adjustment to diagnosis, better ability to

cope with symptoms and protection against depression, hopelessness and desire

of hastened death. Therefore, improving spiritual support in patients’ palliative care

is a valuable task.

8.8.2. Where to get spiritual support services

In health care system, the spiritual support services can be available either as

pastoral care workers (or spiritual care workers) or be invited from outside of the

health care system and are available to support palliative care team. Pastoral care

workers are trained professionals who can help people work through their feelings.

They can also arrange visits from spiritual leaders such as ministers, priests, rabbis

and imams. Where necessary, they can also educate and support others in caring

roles in providing culturally sensitive spiritual care.

If the person is religious, possible spiritual interventions might include (1) visits from

or referrals to chaplains, pastoral care workers or traditional healers, (2) spiritual or

religious counseling and (3) taking part in religious services.

If the person is not religious, possible spiritual interventions might include (1)

creating a life review, (2) support groups, (3) listening to music, (D) creating artwork,(E) enjoying nature, (F) enjoying other leisure activities.

Self-assessment 8.8

1) Case study: You are at hospital where you have a patient suffering from

liver cancer in advanced stage. She is catholic and the family members

need a sacrament for their patient. Where can you find that spiritual

support?2) What is the importance of spiritual support for a palliative care patient?

8.9. Legal and Ethical issues in Palliative care

Learning activity 8.9

Mr. X is hospitalized for 3 months; he was diagnosed of advanced cancer of the

lungs with metastasis in the liver. The treating team has decided to treat him as

palliative care as there is no curative treatment for his advanced lung cancer.

Mr. X has difficulty in breathing and experience severe pain; he is on strong pain

killers and oxygen via face mask. This morning during the ward round he called

the doctor in front of his wife and said that if he had a cardiac arrest he doesn’t

want to be resuscitated and that if he fails in respiratory failure he doesn’t want

any other mean of advanced respiratory support such as mechanical ventilation.

The doctor asked you to give a paper To Mr. X and to sign for his preferences atend of life.

1) Do you think that it is acceptable to accept such request? Explain your

answer2) By respecting Mr. X request which ethical principles are respected.

Learning activity 8.9

Ethics refer to the moral principles that guide behavior and decision making, and

the branch of knowledge and inquiry that deals with moral principles. Guiding moral

principles arise from a variety of beliefs about right and wrong and behavior.

Bioethics is ethics as applied to human life or health (such as decisions about

abortion or euthanasia).

Palliative and end of life issues are often delicate and controversial and require

skilled, insightful interdisciplinary care. Health care providers encounter many

challenges and ethical dilemmas; ethical principles and code conduct guide them

in decision making.

8.9.1. Ethical principles in palliative care/ end of life care

Ethical principles guide decision making in end of life/palliative care. The following

principles should be applied while providing palliative care and end of life care.

Understanding the principles underlying ethics is important for health care providers

and their patients to solve the problems they face in end of life care. The ethical

principles are autonomy, beneficence, no maleficence, fidelity, justice and veracity.

a. Autonomy

Autonomy refers to the right to make one’s own decisions. It is patient’s right to

self-determination. Everyone has the right to decide what kind of care they should

receive and to have those decisions respected. Respecting patient autonomy is

one of the fundamental principles of nursing ethics. This principle emphasizes on

protection of the patients’ right to self-determination, even for patients who havelost the ability to make decisions. This protection can be achieved by using advance

care directives.

Advance care directives (ADs): ADs are derived from the ethical principles of

patient’ autonomy. They are oral and/or written instructions about the future medical

care of a patient in the event he or she becomes unable to communicate, and loses

the ability to make decisions for any reason. ADs completed by competent person

ordinarily include living wills, health care proxies, and “do not resuscitate” (DNR)

orders.

A living will is a written document in which a competent person provides instructions

regarding health care preferences, and his or her preferences for medical

interventions such as feeding tubes that can be applied to him or her in end-of-life

care. A patient’s living will take effect when the patient loses his or her decision

making abilities.

A health care proxy (also called health care agent or power of attorney for health

care) is the person appointed by the patient to make decisions on the patient’s

behalf when he or she loses the ability to make decision. A health care proxy is

considered the legal representative of the patient in a situation of severe medical

impairment. The responsibility of the healthcare proxy is to decide what the patient

would want, not what the proxy wants.

ADs help ensure that patients receive the care they want and guide the patients’

family members in dealing with the decision-making burden. Another reason for

ADs is to limit the use of expensive, invasive, and useless care not requested by

patients. Researches show that ADs improve the quality of end-of-life care and

reduce the burden of care without increasing mortality.

In many countries, the right of people to self-determination is a legal guarantee.

Each patient’s “right to self-determination” requires informed consent in terms of

medical interventions and treatment. A patient has both the “right to demand the

termination of treatment” (e.g. the discontinuation of life support) and the “right to

refuse treatment altogether”; the exercise of these rights is strictly dependent on

the person. ADs can be updated yearly and/or prior to any hospitalization.

In many countries, the right of competent individuals to express their treatment

preferences autonomously in end-of life care should be met with ethical respect,

taking into account the use of advanced treatments and the prognosis of their

disease. However, this autonomy has some limitations. The decisions made by

a patient should not harm him or her. It is important for healthcare providers to

respect the autonomy of their patient and fulfill their duties to benefit their patientswithout harming them.

b. Non-maleficence

Non-maleficence is the duty to ‘do no harm’. Although this would seem to be

a simple principle to follow, in reality it is complex. Harm can mean intentionally

causing harm, placing someone at risk of harm and unintentionally causing harm.

However, placing a person at risk of harm has many facets. A person may be at risk

of harm as a known consequence of a nursing intervention intended to be helpful.

For example, an individual may react adversely to a medication. Unintentional harm

occurs when the risk could not have been anticipated.

Although some of the nursing interventions might cause pain or some harm, non

maleficence refers to the moral justification behind why the harm is caused. Harm

can be justified if the benefit of the nursing intervention is greater than the harm to

the patient and the intervention is not intended to harm the patient.

c. Beneficence

Beneficence means ‘doing good’. Nurses are obligated to do good; that is, to

implement actions that benefit individuals. However, doing good can also pose

a risk of doing harm. Beneficence requires physicians to defend the most useful

intervention for a given patient. Often, patients’ wishes about end-of-life care are

not expressed through ADs, and the patients’ health care providers and family

members may not be aware of their wishes about end-of-life care.

If a patient is not capable of decision-making, or if the patient has not previously

documented his or her wishes in the event he or she becomes terminally ill, the

end-of-life decision is made by the patient’s Health care provider as a result of

consultations with the patient or the patient’s relatives or the patient’s health care

proxy. In this situation, the responsibility of the Health care provider in the care of

the dying patient should be to advocate the approaches that encourage the delivery

of the best care available to the patient.

d. Justice

Justice is often referred to as fairness. Nurses face decisions where a sense of

justice should prevail. Healthcare providers have an ethical obligation to advocate

for fair and appropriate treatment of patients at the end of life. This can be achieved

through good education and knowledge of improved treatment outcomes.

e. Fidelity

Fidelity means to be faithful to agreements and promises. By virtue of their standing

as professional caregivers, nurses have responsibilities to people in their care,

employers and society, as well as to themselves. Nurses often make promises such

as ‘I’ll be right back with your pain medication’ or ‘I’ll find out for you’. Individuals

take such promises seriously and nurses are obliged to respond within appropriate

time frames. Fidelity principle requires Health Care providers to be honest with their

dying patient about the patients’ prognosis and possible consequences of patients’

disease.

f. Veracity

Veracity refers to telling the truth. Although this seems straight forward, in practice

choices are not always clear. Should a nurse tell the truth when it is known that it will

cause harm? Does a nurse lie when it is known that the lie will relieve anxiety and

fear? Lying to sick or dying people is rarely justified. The loss of trust in the nurse

and the anxiety caused by not knowing the truth usually outweigh any benefits

derived from lying. Truth telling is fundamental to respecting autonomy.

Most patients want to have full knowledge of their disease and its possible

consequences, but this desire may decrease as they approach the end of their life.

Some patients may not want information about their disease. Health care providers

should be skilled in determining their patients’ preferences for information and,

honestly yet sensitively, provide their patients with as much accurate information

as the patients want. Having effective patient-centered communication skills helps

Health Care providers learn and meet the demands of their patients.

8.9.2. Ethical issues in end of life and Palliative care

In the end of life care of a patient, the decision to implement practices to prolong the

patient’s life or to comfort the patient may be difficult for the Health care providers,

patient, family members or health care proxy. The following topics relate to some

situations where difficulty in decision making regarding end of life is encountered:

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), advanced respiratory support such as

Mechanical ventilation (MV), artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH), terminal

sedation, withholding and withdrawing treatment, euthanasia and physician

assisted suicide (PAS).

a. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation(CPR)

Although CPR is valuable in the treatment of heart attacks and trauma, sometimes

the use of CPR may not be appropriate for dying patients and may lead to

complications and

Worsen the patients’ quality of life. For some terminally ill patients, CPR is an

undesired intervention. The decision not to perform CPR on a dying patient can

be difficult for healthcare personnel. The decision to administer CPR to a patient

depends on many factors such as patient preferences, the estimated success rate,

the risks of the procedure, and the perceived benefit.

A competent patient may not want to undergo CPR in the event of cardiopulmonary

arrest. This decision is called the” Do not attempt CPR” (DNR decision). Despite

this request, the patient’s family members may ask the Health Care provider to

perform CPR. In this case, if the patient is conscious and has the ability to make

decisions, the patient’s decision is taken into account. Physicians must learn the

CPR demands of patients at risk of cardiopulmonary arrest. DNR decision can be

considered for the following patients

• Patients who may not benefit from CPR;

• Patients for whom CPR will cause permanent damage or loss of consciousness;

• Patients with poor quality of life who are unlikely to recover after CPR.

b. Advanced respiratory support: Mechanical ventilation

Approximately 75% of dying patients experience difficulty breathing or dyspnea.

This feeling can be scary for patients and those who witness it. In end-of-life care,

mechanical ventilation is applied not to prolong the lives of patients but to reduce

their anxiety and to allow them to sleep better and eat more comfortably.

If Mechanical ventilation support does not provide any benefit to the patient or no

longer meets its intended goals, or if the outcome is not optimal, or the quality of

life is not acceptable according to the patient’s or family’s wishes, support can be

terminated. The timing of the device separation should be chosen by the patient’s

family members.

c. Advanced Nutrition and Hydration(ANH)

Nutrition and hydration are essential parts of human flourishing. ANH involves

giving food and water to patients who are unconscious or unable to swallow.

Artificial nutrition can be given through enteral feeding by tube or parenteral feeding.

Nutrition and hydration decisions are among the most emotionally and ethically

challenging decisions in end-of-life care. Many medical associations suggest that

feeding and hydration treatments are forms of palliative care that meet basic human

needs and must be given to patients at the end of life.

ANH may improve the survival and quality of life of some patients. It may improve

the nutritional status of patients with nutritional problems. ANH is associated with

considerable risks such as the aspiration pneumonia, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal

discomfort.

For these reasons, the benefits and possible harms of the intervention should be

explained to the patient or to the other decision-makers in detail before making the

ANH decision.

If a patient is incompetent, his or her proxy decision-maker can refuse artificial

feeding and hydration on behalf of the patient.

d. Terminal Sedation

Terminal sedation is a medical intervention used in patients at the end of life, usually

as a last effort to relieve suffering when death is inevitable. Sedatives are used forterminal sedation. People have some concerns about terminal sedation because

the treatment of an unconscious patient is sensitive and risky. The purpose of

terminal sedation is not to cause or accelerate death but to alleviate pain that is

unresponsive to other means.

There are four criteria for evaluating a patient for terminal sedation:

• The patient has a terminal illness.

• Severe symptoms are present, the symptoms are not responsive to treatment,

and the symptoms are intolerable to the patient.

• A “do not resuscitate” order is in effect.

• Death is imminent (hours to days).

e. Withholding and Withdrawing treatment

Withdrawing is a term used to mean that a life-sustaining intervention presently

being given is stopped. Withholding is a term used to mean that life-sustaining

treatment is not initiated or increased.

The decision to withhold or withdraw interventions or treatment is one of the

difficult decisions in end-of-life care that causes ethical dilemmas. If a patient and

physician agree that there is no benefit in continuing an intervention, the right action

is withholding or withdrawing the interventions.

In most countries, the legal opinion is that patients cannot seek treatment that is

not in their best interest and, that physicians should not strive to protect life at all

costs. However, if there is doubt, the decision must be in favor of preserving life. All

healthcare professionals should be able to define an ethical approach to making

decisions about withholding and withdrawing treatment that takes into account the

law, government guidance, evidentiary base, and available resources.

f. Euthanasia

Euthanasia, is a Greek word meaning ‘good death’, Euthanasia is applied in two

ways as active or passive euthanasia.

Active euthanasia involves actions to bring about an individual’s death directly. In

active euthanasia, a person (generally a physician) administers a medication, such

as a sedative and neuromuscular relaxant, to intentionally end a patient’s life at the

mentally competent patient’s explicit request.

Passive euthanasia: Passive euthanasia occurs when a patient suffers from

an incurable disease and decides not to apply life-prolonging treatments. More

commonly referred to now as withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining therapy,

involves the withdrawal of extraordinary means of life support, such as removing

a ventilator or withholding special attempts to revive an individual (e.g. a ‘not for

resuscitation’ status) and allowing the individual to die of the underlying medicalcondition.

Euthanasia is not accepted legally and ethically in many counties worldwide

including Rwanda.

8.9.3. Strategies to enhance ethical decisions and practice

Several strategies help nurses overcome possible organizational and social

constraints that may hinder the ethical practice of nursing and create moral distress.

As a nurse, the following should be taken into consideration:

• Become aware of your own values and the ethical aspects of nursing.

• Be familiar with nursing codes of ethics.

• Seek continuing education opportunities to stay knowledgeable about ethical

issues in nursing.

• Respect the values, opinions and responsibilities of other health care

professionals that may be different from your own.

• Where possible, participate in or establish ethics rounds. Ethics rounds use

hypothetical or real cases that focus on the ethical dimensions of the care of

the individual rather than the individual’s clinical diagnosis and treatment.

• Serve on institutional ethics committees.

• Strive for collaborative practice in which nurses work effectively in cooperation

with other health care professionals.

Other patients’ rights

All patients have a right to dignity throughout their life, especially when the end of

life is near. Provide privacy when bathing or caring for a patient. Encourage the

person to make choices and control their own life. If they want to wear a certain

dress, let them wear it. If they want their bath in the evening instead of the morning,

let them have their bath in the evening. Allow the person to be as independent as

possible, speak to the person with respect and call the patient by their name.

All patients that are capable of making a decision must be able to do so, even when

the end of life is near. Patients have a right to have their medical information secret

and private. Never discuss a patient or their condition with friends, neighbors, other

patients or residents. Do not discuss any information about the patient unless the

patient asks you to.

Keep patient information confidential. It is against the law to tell your family member

or neighbor that a patient named x, my patient is dying with AIDS.

Nursing care does not stop when the end of life comes. All members of the health

care team play a very important role in the end-of-life care. This care meets the

person’s physical, mental, social, spiritual and financial needs. Nurse and others

health team must be able to meet these needs. Care at the end of life is a veryrewarding part of nursing care.

Furthermore, the patient has right to be treated as a living human being until He/she

die, right to maintain a sense of hopefulness, the right to express the feelings and

emotions about the approaching death in the patient own way, right to participate

in decisions concerning his care, right to expect continuing medical and nursing

attention even though cure goals must be changed to comfort goals, right not to die

alone, right to be free from pain, right to have questions answered honestly, right

to die in peace and dignity, right to discuss and enlarge patient religious and or

spiritual experiences, whatever these may mean to others and right to expect thatthe sanctity of the human body will be respected after death.

Self-assessment 8.9

1) What are advance care directives? What is its purpose in end of life care?

2) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is lifesaving intervention; however

in some circumstances a decision of Do not attempt Resuscitation (DNR)

may be made; for which patients a DNR may be considered?

3) In end of life care; termination sedation may be administered to

patients; What are criteria should the health care provider assess before

administration of termination sedation.

4) Define euthanasia and explain its main types

5) In caring patient in palliative care nurses may encounter constraints that

may hinder the ethical practice of nursing and create moral distress. Give4 strategies that will help the nurse to overcome those constraints?

8.10. Communication in palliative care

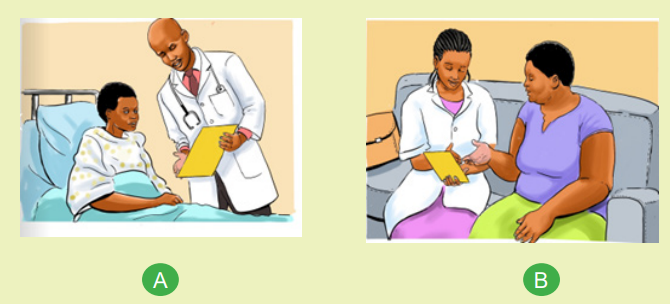

Learning activity 8.10

1) In which context may you encounter image A and B?

2) Which message pictures A and B communicate to you?

In situations of serious illness, communication is one of the most important tools

which the health care professionals use in giving the patient the information that

they need to know. This creates a sense of trust and security for both the patient

and the family.

Communication is the exchange of information, thoughts and feelings among

people using speech or other means. In healthcare, it is approaching every patient

interaction with the intention to understand the patient’s concerns, experiences,

and opinions.

Communication is a vital basic pre-requisite for all health care providers to provide

effective quality of care for all patients and not just in the palliative care; however

Palliative care requires excellent communication skills because at this time

communication can be particularly challenging due to patient clinical situations

where suffering, fear, and confusion can be considerable. Communication in

palliative care involves the conversation between patient, family and health care

provider about goals of care, transitions in care, progress of disease and providing

social, psychological & spiritual support. Communication can never be neutral; it is

either effective or ineffective, stress relieving or stress inducing.

The approach in communicating information, predictions, and prognoses to patients

and loved ones will have a crucial effect on their current and future behavior, as well

as potentially on treatment and illness outcomes.

Communication should be done in sense of Sensitive, honest and empathic in order

to relieve the burden of difficult treatment decisions, and the physical and emotional

complexities of death and dying, and lead to positive outcomes for people nearing

the end of life and their companions.

Effective and efficient communication is crucial for providing care and support to

people affected by life-limiting illness. However, some people are not familiar to

discussing personal psychological issues and can find these conversations difficult

Importance of communication in palliative care

Good communication between healthcare professionals and patients can lead to a

greater sense of well-being, decreasing feelings of distress commonly experienced

by those diagnosed with a terminal illness and their families.

Communication in palliative care help patients to understand their disease,

outcomes, patient behavior, ability to cope, both physical and psychological health,

as well as patient satisfaction with care, and compliance with treatment.

Also, good communication in palliative care was found to be effective in prevention

of depression and other stress related, helps patient to participate in decisionmaking during care and improve psychological and physical well-being.

Open communication is an important aspect of death and dying and of a good death

and it is thought to contribute to effective symptom control and end of life planning.

By contrast, poor communication is associated with distress, complaints and

can result in the patient -family having significant misunderstanding of end-of-life

processes.

Behavior of nurse in palliative care

During communication, the health care provider should possess the following

behavior in order to contribute in patient’s sense of hope including being present