UNIT 8:AUDIT EVIDENCE AND SAMPLING

Key unit competence: To be able to explain the audit procedures in

sampling and gathering audit evidence

Introductory activity

Observe the above picture then answer the following questions:

1. What do you think this auditor is looking for?

2. Is it necessary that this auditor can check all of these documents? If

yes or no explain.

3. What this auditor can use to find what he/she is looking for?

4. Is it possible that this auditor can do his/her auditing activities by

using the computer? If yes or no explain.

8.1. Audit execution and procedures

Learning activity 8.1

Observe the picture above then answer the following questions:

1. How do we call the terms in small circles surrounding the big circle?

2. Why these terms surround the big circle named audit execution?

8.1.1. Meaning and steps of audit execution

a) Meaning of audit execution

The audit execution consists mainly on the assessment and valuation of the

questions based on the replies in the audit, the determination of the audit result

and the degree of fulfilment, and the rating of the audit. In audit execution, the

auditor has to perform audit procedures i.e. test of controls and substantive

tests. The tests are perfomerd on class of tranactions and balances sampled.

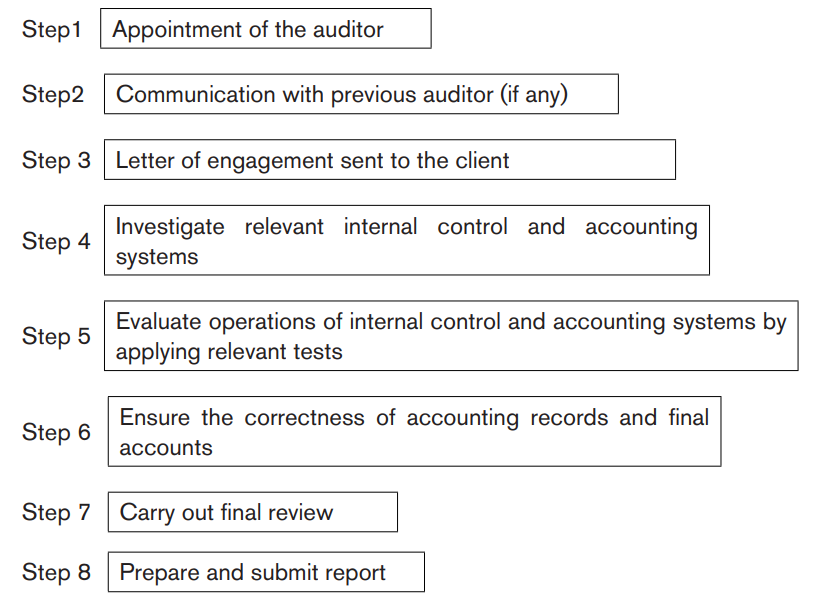

b) Steps of audit execution

The conduct of an audit execution involves various procedures and techniques.

These are various steps, which are taken by the auditor to complete an audit.

These steps are illustrated with the help of the following figure:

The steps involved in the conduct of audit execution are further explained as

under:

• The auditor is appointed by the members or shareholders of a

company. The auditor should make it sure that his/her appointment is in

accordance with provisions of companies Act;

• If the auditor has been appointed in place of another auditor, he/she

should enquire from the retiring auditor, the reasons for his/her removal

as an auditor. If the retiring auditor discloses some information due

to which the new auditor would not be able to work independently

or in accordance with the professional ethics, then he/she should not

accept the appointment;

• When the auditor accepts the appointment then he/she should obtain

definite instructions from his/her client about the nature and scope

of his/her work and duties, for this purpose, the auditor writes an

engagement letter to the client;

• The next step is to investigate relevant internal control and accounting

systems of the company. In this case, he/she obtains a list of the

books maintained and the details of internal systems established in

the respective organization. He/she opens an audit file and draws

up internal control questionnaires (I.C.Q). At this stage, he/she alsoprepares an audit programme;

• The auditor carries out audit work to evaluate the operation of internal

control and accounting systems of the concerned company. For thispurpose, he/she applies various compliance and substantive tests;

• The auditor obtains audit evidence to ensure that all accounting records

have been maintained accurately and the financial statements preparedfrom these records are also correct;

• The auditor reviews his/her findings critically in order to form his/heropinion.

• Finally, the auditor prepares his/her audit report and submits this reportto the members of the company or to the concerned parties.

8.1.2. Audit procedures

a) Meaning of audit procedures

Audit procedures are the techniques, processes, and methods that auditors use

to obtain reliable audit evidence, which enable them to gain a sound judgment

about an organization’s financial status. Audit procedures are conducted to

help determine whether or not a company’s financial statement is credible andfactual.

The regular implementation of these procedures helps establish a business’s

financial reputation and strengthen its trustworthiness in the eye of its customers,the market, and potential investors.

There is no definitive structure when it comes to auditing; its whole process

would depend on the auditor, the company to be audited, and the purpose ofthe audit. Learn more about the three main methods of audit procedures below.

• Tests of controls

Tests of controls are audit procedures designed to evaluate the operating

effectiveness of controls in preventing, or detecting and correcting materialmisstatements at the assertion level.

Tests of controls are performed only on those controls that the auditor has

determined and suitably designed to prevent, or detect and correct a material

misstatement in an assertion. If substantially different controls were used at

different times during the period under audit, each control is consideredseparately.

Testing the operating effectiveness of controls is different from obtaining an

understanding and evaluating the design and implementation of controls.

However, the same types of audit procedures are used. The auditor may

therefore, decide it is efficient to test the operating effectiveness of controls at

the same time as evaluating their design and determining that they have beenimplemented.

• Substantive procedures

Substantive procedures are audit procedures designed to detect materialmisstatements at the assertion level.

• Analytical procedures

Analytical procedures pair financial data with non-financial data determine

the correlation between them. Comparison of previous trends versus current

trends, as well as evaluation of the difference between the client’s record andthe substantive evidence, are also considered analytical procedures.

Application activity 8.1

1. Audit execution is said when :

a. audit is done

b. Audit start

c. Audit take place

d. Audit is concluded

e. a and c are correct answersf. All of the above

2. Differentiate substantive procedures from analytical procedures

8.2. Audit evidence

Learning activity 8.2

Mr. GAKIRE is an external auditor in XYZ company. During his audit activities,

he has discovered some fictious transactions and other frauds in their

books of accounts and financial statement. At first, Mr. GAKIRE thought

that the frauds were committeded by some of the staff at managerial level,

especially the managing director, and other staff working in sensitive areas

like the cashier and the storekeeper but he did not have the information

appropriate information to support it. He started by looking at the information

within the company that can help him to confirm who were responsible

for frauds and failed to get them. Leter, he decided to visit some of the

company’s third parties like banks, suppliers, creditors and debtors with the

aim of identifying the persons who were involved in the frauds. At the end,

Mr. GAKIRE discovered that the frauds were committed by the managingdirector, accountant, and cashier.

After reading the above scenario answer the following questions:

1. What is the technical term used for the information found by Mr.

GAKIRE?

2. How do we call the means used by Mr. GAKIRE when he was

searching information? And which one has he used?

3. Is Mr. GAKIRE allowed to accept any kind of information receivedfrom XYZ’s third parties? If yes or no, explain.

8.2.1. Meaning of audit evidence

Audit evidence is all the information, whether obtained from audit procedures or

other sources that is used by the auditor in arriving at the conclusion on which

the auditor’s opinion is based on. The auditor obtains evidence from severalsources. Some of significant source of audit evidence are from:

• Accounting records;

• Audit procedures performed to test accounting records;

• Information obtained during the audit of previous years;

• Audit firm’s quality control procedures for acceptance of audit;

• Work of management’s expert;

• Confirmation from third parties;

• Comparable data of other companies engaged in the same industry;

• Written representations from management to support other evidencesobtained during the audit.

8.2.2. Qualities of audit evidence

There are a number of general principles set out in ISA 500 to assist the auditor

in assessing the relevance of audit evidence. These can be summarized asfollows:

a) Sufficiency

It means that audit evidence should be complete and adequate to prove any

material fact. For example, complete physical counting of items of stock issufficient to verify the value of stock.

The auditor must assess whether the evidence is sufficient to allow him/her to

reach the opinion that the financial statements give a true and fair view. If the

auditor decides that the evidence obtained is insufficient to reach this opinion

(or any other opinion), he/she may take any other action depending on the

circumstances that can allow him/her to obtain more evidence by means oftests of controls and substantive procedures.

b) Relevance

Audit evidence should be relevant to the purpose for which it is required. For

example, checking of physical existence of assets in accordance with theschedule of assets is relevant for audit purposes.

c) Reliability

Evidence is reliable if it is considered correct and accurate. For example, if the

auditor receives a certificate of stock valuation from an outsider expert instead

of an official of the company then it is more reliable. Similarly, documentary

evidence instead of oral evidence is more reliable. A physical inspection by theauditor himself/herself is more reliable than evidence obtained from others.

8.2.3. Types of Audit evidence

There are four main types/groups of audit evidences are:

a) Primary audit evidence

This is the type of evidence which the auditor gathers from within the company,

basically from accounting records and source documents. This type of audit

evidence is usually biased or may fall-short of some fact, which renders it lessreliable.

b) Secondary audit evidence

This is the type of audit evidence which the auditor collaborates outside the

company, i.e. which gathers from such sources as third parties ‘confirmation,

e.g. debtors, creditors, bankers, trustees, etc. and this evidence is gathered

by writing to these parties and requesting them to send replies directly to the

auditor. This evidence is usually more reliable except where these parties have

other special relationships with the company in which case they may collude togive biased information.

c) Circumstantial Audit evidence

This evidence is gathered from circumstances prevailing in a given business at

the time of the audit, e.g. orderliness of the business which is an indication of

strong internal control system, qualification and ability of the staff to co-operate

with the auditor, etc. This evidence may prove to be biased in particular if theauditor’s visit was known by the client in advance.

d) Hearsay evidence

This is gathered from such sources as: interviews, conversation, posing

intelligent questions to the client’s senior staff and other parties related to theclient in their day-to-day deals.

8.2.4. Techiniques of gathering audit evidence

A number of audit testing procedures are available to the auditor as a means of

gathering audit evidence. More than one procedure may be used in collectingevidence in a particular area.

Not all procedures may be appropriate to a given objective of the audit. The

auditor should select the most appropriate procedure in each situation. ISA 500

identifies seven (7) main testing procedures for gathering audit evidence:

• Inspection (of an item)

• Observation (of a procedure)

• Inquiry

• External confirmation

• Recalculation

• Reperformance• Analytical procedures

Application activity 8.2

1. Primary audit evidence is an evidence the auditor gathers from:

a. Inside the company

b. Source documents

c. Accounting records

d. A and C are correct answers

e. All of the above

2. The following audit procedures are used for gathering audit evidence

except:

a. Staff confirmation

b. Recalculation

c. Inquiry

d. Checking procedure

e. A and D are correct answers

f. No one of the above

3. Hearsay evidence is an audit evidence obtained from the followings

except:

A. Interviews

b. Written conversations

c. Questioning

d. Oral presentationse. No one of the above

4. Enumerate sources of audit evidence.

8.3. Audit sampling

Learning activity 8.3

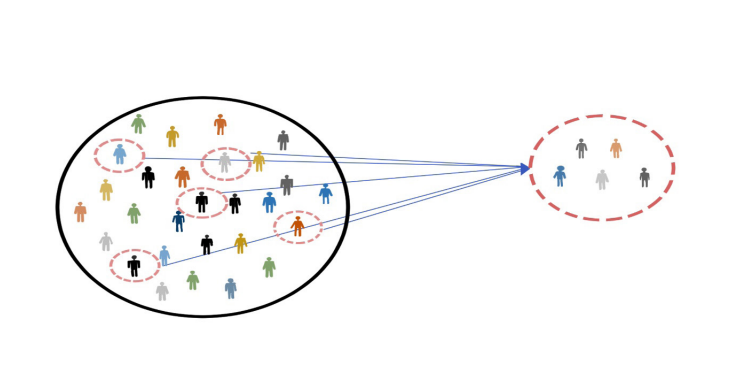

Observe the above image, answer the questions below:

1. What auditing term can be used for these people in the big circle?

2. What is the term used in auditing for the people who are selected in

the big circle then move in the small circle?

3. What do you think can be based on when selecting these people inthe small circle?

8.3.1. Meaning of audit sampling

a) Meaning

Audit sampling is the application of audit procedures to less than 100% of

items with a population of audit relevance such that all sampling units have a

chance of being selected. This will enable the auditor to obtain and evaluate

audit evidence about some characteristics of the items selected in order to

provide the auditor with reasonable basis on which to draw conclusions about

the entire population. Audit sampling can be applied using either statistical ornon-statistical approaches.

Auditors do not normally examine all the information available to them as it would

be impractical to do so and using audit sampling will produce valid conclusion.ISA 530 Audit sampling provides guidance to auditors.

Notes: Some testing procedures do not involve sampling, such as:

• Testing 100% of items in a population

• Testing all items with certain characteristics as selection is notrepresentative

Auditors are unlikely to test 100% of items when carrying out test of controls,

but 100% testing may be appropriate for certain substantive procedure. For

example, if the population is made up of a small number of high value items, there

is a high risk of material misstatement and other means do not provide sufficientappropriate audit evidence, then 100% examination may be appropriate.

The auditor may alternatively select certain items from population because of

specific characteristics they possess. The results of items selected in this way

cannot be projected onto the whole population but may be used in conjunctionwith other audit evidences concerning the rest of the population.

• High value or key items. The auditor may select high value items oritems that are suspicious. Unusual or phone error.

• All items over a certain amount. Selecting items, this way may mean

a large proportion of the population can be verified by testing a fewitems.

• Items to obtain information about the client’s business, the nature oftransactions, or the client’s accounting and control systems.

• Items to test procedures, to see whether particular procedures arebeing performed.

In designing the audit sampling, the auditor applies judgment in considering:

• Audit objective

• Population

• Sampling unit

• Risk and assurance

• Tolerable error

• Expected error in the population, and• Stratification

Audit objective: the auditor should first consider the specific audit objectives to

be achieved to enable him/her to determine the audit procedure or combination

of procedures which is likely to best achieve those objectives. In addition, when

audit sampling is appropriate, the nature of the audit evidence sought and

possible error conditions or other characteristics relating to that evidence will

assist the auditor in defining what constitutes an error and what populationshould be used for sampling.

The population: the population is the entire set of data from which a sample is

selected and about which the auditor wishes to draw conclusions. The auditor

should determine that the population from which he/she draws the sample is

appropriate for the specific audit objective. For example, if the auditor’s objective

was to test for overstatement of accounts receivable, his/her population could

be defined as the accounts received trial balance.

Sampling unit is the individual items constituting a population. It may be a

physical item (e.g. credit entries on bank statements, sales invoices, receivables’balances) or a monetary unit.

Risk and assurance: in planning the audit, the auditor uses professional

judgment to assess the level of audit risk that is appropriate. Audit risk means

the chance of damage to the audit firm as result of giving an audit opinion thatis wrong in some particular.

Tolerable error: tolerable error is the maximum error in the population that

the auditor would be willing to accept and still conclude that the result from

the sample has achieved his/her audit objective. Tolerable error is considered

during the planning stage and is related to the auditor’s preliminary judgment

about materiality. The smaller the tolerable error, the larger the sample size theauditor will require.

Expected error in the population: if the auditor expects error to be present,

he/she will normally have to examine a larger sample to conclude either that

the population values are fairly stated to within the planned tolerable error or

that the planned reliance on a relevant control is justified. Smaller sample sizes

are justified when the population is expected to be error free. In determining

the expected error in a population, the auditor should consider such matters

as error levels identified in previous audits changes in client procedures and

evidence available from his/her evaluation of the system of internal control andfrom results of analytical review procedures.

Stratification: stratification is the process of dividing population into sub-

populations, which is a group of sampling units, which have similar characteristics

(often in monetary value). The strata must be explicitly defined so that each

sampling unit can belong to only one stratum. This procedure reduces the

variability of the items within each stratum. Stratification enables the auditor to

direct his/her efforts towards the items he/she considers potentially contain the

greater monetary error. For example, the auditor might direct his/her attention

to larger value items for accounts receivable to detect material overstatementerrors. In addition, stratification may result in a smaller sample size.

8.3.2. Sample size

The auditor shall determine a sufficient sample size to reduce sampling risk toan acceptably low level.

a) Sampling risk

Sampling risk is the risk that the auditor’s conclusion, based on a sample of a

certain size, may be different from the conclusion that would be reached if the

entire population weas subjected to the same audit procedure.

Non-sampling risk is the risk that the auditor might reach an erroneous

conclusion for any reason not related to sampling risk. For example, most

audit evidence is persuasive rather than conclusive, the auditor might use

inappropriate procedures, or the auditor might misinterpret evidence and fail torecognize a misstatement or deviation.

Remember: Detection risk is the risk that auditors will not detect a material

misstatement in the financial statements. Sampling risk is a subset of detection

risk, being the risk that the sample is not representative of the population. This

means that the auditor’s sample may not include an item, which contains a

material error, and so the material misstatement would not be detected.

The auditors are faced with sampling risk in both tests of controls and substantiveprocedures, as follows.

The risk the auditor will conclude, in the case of a test of controls, that controls

are more effective than they actually are, or in the case of a test of details that

a material misstatement does not exist when in fact it does. This type of risk

affects audit effectiveness and is more likely to lead to an inappropriate auditopinion.

The risk the auditor will conclude, in the case of a test of controls, that controls

are less effective than they actually are, or in the case of a test of details, that

a material misstatement exists when in fact it does not. This type of risk affects

audit efficiency, as it would usually lead to additional work to establish that initialconclusions were incorrect.

Auditors need to ensure that risk is managed, so the greater their reliance on the

results of the procedure in question, the lower the sampling risk auditors will be

willing to accept and the larger the sample size will be. The sample size needed

to give acceptable level of audit risk will depend on the assessed levels of

inherent risk and control risk. The higher these risks are, the greater the samplesize needed to offset this.

If both inherent risk and control risk are low, then a smaller sample size will be

necessary than for situations where inherent or control risks are considered tobe high.

For both tests of controls and substantive tests of details, sampling risk can be

reduced by increasing sample size while non-sampling risk can be reduced byproper engagement planning, supervision and review.

b) Risk and sample size

If you recall, in the previous unit we illustrated how the prescribed level of

detection risk is affected by inherent risk and control risk, given a desired

level of audit risk. This relationship is described by the audit risk model: AR =IR*CR*DR.

This formula is very important, so we will look at another example of it here, toreinforce your understanding.

An audit firm sets its acceptable level of risk as 5%. The risk assessment

activities at the firm’s client have indicated that the level of inherent risk is 75%

and control risk is 40%. What is the level of detection risk the auditor canaccept?

Applying the audit risk formula:

AR= IR*CR*DR

DR = AR / IR*DR

DR= 0.05 / 0.75*0.4

DR= 0.05 / 0.3

DR= 0.16666667= 0.167*100= 16.7%

AR= 0.75*0.4*0.167AR= 0.0501*100= 5%

So, the level of detection risk would need to be set at 16.7% to achieve the

prescribed level of audit risk (5%).

However, we have now also seen that detection risk comprises both sampling

risk and non-sampling risk.

To reflect this, the audit risk model can be rewritten:

Audit risk = Inherent risk * Control risk * Sampling risk (SR) * Non-sampling risk(NSR)

As above, the audit firm sets its acceptable level of risk as 5%, the level of

inherent risk is 75% and control risk is 40%. However, in addition, the firm

has identified that non-sampling risk is 50%. What is the prescribed level ofsampling risk?

Applying the amended audit risk formula, we find that:

AR= IR*CR*SR*NSR

SR= AR / IR*CR*NSR

SR= 0.05 / 0.75*0.4*0.5

SR= 0.05/0.15

SR= 0.33333333*100= 33%

AR= 0.75*0.4*0.5*0.33AR= 0.05*100= 5%

So, the level of sampling risk would now need to be set at 33%.

Calculating the actual sample size to be used for an audit test is a complex

exercise involving mathematical tables, and is outside the scope of this paper.You will not have to perform such a calculation in your exam.

However, you need to appreciate, in general terms, the relationship between

the level of sampling risk and the size of the sample an auditor will need to

choose. That is, the lower the sampling risk the auditor is prepared to accept,

the larger the sample size he/she will have to select. Or conversely, the higher

the sampling risk the auditor is prepared to accept, the smaller the sample sizehe/she will have to select.

8.3.3. Techniques of audit sampling

Audit sampling can be done using either statistical sampling or non-statisticalsampling methods.

Statistical sampling is sampling method involving random selection of the

sample items, and the use of probability theory to evaluate sample results,including measurement of sampling risk.

Non-statistical sampling is another sampling method that does not have thesecharacteristics.

There are a number of methods available to an auditor to help him/her select asample (ISA 530).

a. Random selection uses random number tables or computerized generatorto select the sample.

b. For example, the auditors might tell a computer program there are 450

receivables numbered 1–450 and they want a sample of 30. The computer

would randomly select 30 numbers between 1 and 450 to be the sampleditems.

c. Systematic selection involves selecting items using a constant interval

between selections, the first interval having a random start. So using the

above example of 1–450 again, the sampling interval would be 15, as 15*30

is 450. The computer could randomly choose a number between 1 and 15

to be the 1st sampled item and every 15th item after that (for example, 13,

28, 43 etc.) would be sampled. When using systematic selection auditors

must ensure that the population is not structured in such a manner that thesampling interval corresponds to a particular pattern in the population.

d. Haphazard selection is where an auditor himself/herself selects items

‘at random’. It may be an alternative to random selection provided that

the auditors are satisfied that the sample is representative of the entire

population. This method requires care to guard against making a selection

which is biased, for example towards items which are easily located, as they

may not be representative. It should not be used if auditors are carrying outstatistical sampling.

e. Sequence or block selection. Sequence sampling may be used to establish

whether certain items have particular characteristics. For example: an auditor

may use a sample of 50 consecutive cheques to verify whether cheques

are signed by authorized signatories rather than picking 50 single cheques

throughout the year. Sequence sampling may however produce samples

that are not representative of the population as a whole, particularly if errors

only occurred during a certain part of the period, and hence the errors foundcannot be projected onto the rest of the population.

f. Monetary unit sampling is a type of value-weighted selection in which

sample size, selection and evaluation result in a conclusion in monetaryamounts.

The auditor shall perform audit procedure, appropriate to the purpose, on eachitem selection.

If the particular item is not appropriate, tests can be performed on alternativeitems

If however, evidence about the item is not available, the auditor should normally

treat it as an error. For example, if an auditor has chosen a selection of

receivables balances to confirm whether they have subsequently been paid and

one sampled item was actually in credit due to a previous double payment, it

would not be appropriate to test for a subsequent payment and another balanceshould be selected.

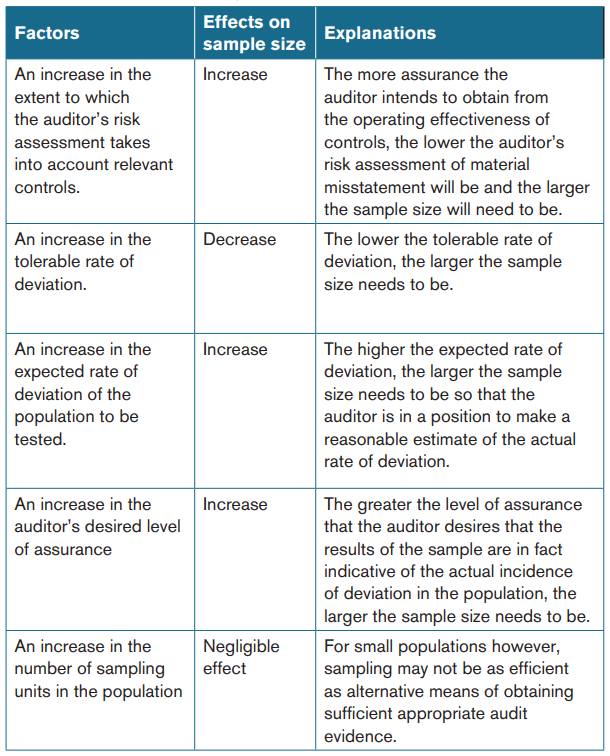

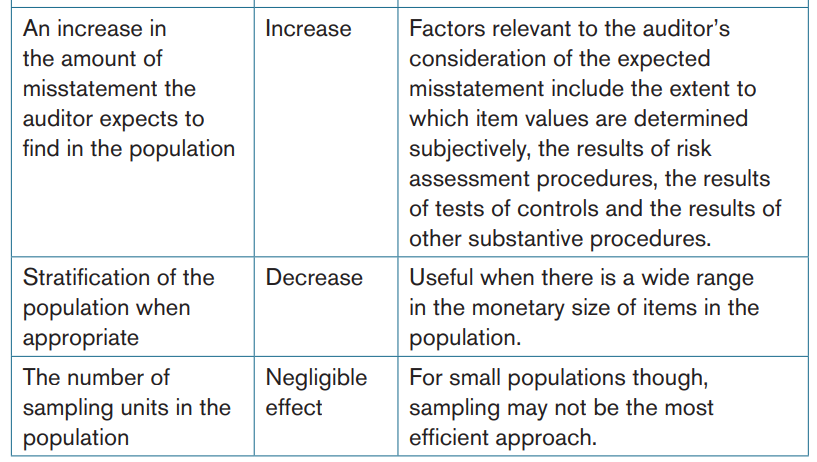

8.3.4. Factors affecting the sample size

Examples of some factors affecting sample size are given in ISA 530, andsummarized here:

Examples of factors influencing sample size for tests of controls:

Examples of factors influencing sample size for tests of details

An important thing to note is that although the auditor can manage/influence the

level of audit risk by increased sampling, this should always be balanced againstthe amount of time and resource available.

Application activity 8.3

1. Give three examples of sample selection methods that can be used

in audit sampling.

2. Differentiate sampling risk from non-sampling risk.

3. Explain the importance of audit sampling during the audit execution.

4. What are the testing procedures that do not involve sampling?

5. State the elements that the auditor may depend upon when designingthe audit sampling before applying judgement.

8.4. Audit in IT environment

Learning activity 8.4

Observe the above picture then answer the following questions:

1. How do we call applications of auditing procedures that can be

performed with the use of a computer as an audit tool?2. What are those applications?

8.4.1. Computer Assisted Audit Techniques(CAATs)

a) Meaning of CAATs

Computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) are commonly used by auditors.They consist of audit software and test data.

Computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) are applications of auditingprocedures to be applied using the computer as an audit tool.

It is by no means unusual to use a computer to help with auditing. You probablyuse common CAATs all the time in your daily work without realizing it.

Most modern accounting systems allow data to be manipulated in various waysand extracted into a report.

Even if reporting capabilities are limited, the data can often be exported directly

into a spreadsheet package (sometimes using simple Windows-type cut andpaste facilities in very modern systems) and then analyzed.

Most systems have searching facilities that are much quicker to use thansearching through print-outs by hand.

There is a variety of packages specially designed either to ease the auditing task

itself, or to carry out audit interrogations of computerized data automatically.

There is also a variety of ways of testing the processing that is carried out.

Much of this work can now be done using computers that are independent ofthe organization’s systems.

These uses of the computer for audit work are known as computer-assisted

audit techniques (CAATs). CAATs may be used in performing various auditing

procedures, including the following:

• Tests of details of transactions and balances

• Analytical review procedures• Tests of computer information system controls

The overall objectives and scope of an audit do not change when an audit is

conducted in a computerized environment. Auditing can be carried out around,through or with the computer.

b) Auditing around the computer

To audit around the computer, the auditor does not look at the specific workings

of the system itself. A sample of inputs will be traced to outputs, and vice versa.

If they prove to be accurate and valid, it is assumed that the system of controlsis effective and that the system is operating properly.

The main advantage of this method of auditing is that it can be carried out with

very little technical expertise. However, this method is only suitable if there is a

clear audit trail within the system, the system is relatively simple, and up to datedocumentation exists about how the system works.

c) Auditing through the computer

Auditing through the computer requires more specific IT audit skills than those

required to audit around the computer as this method directly tests the controlswithin the system itself.

Auditors customarily audit ‘through the computer’. This involves an examination

of the detailed processing routines of the computer to determine whether the

controls in the system are adequate to ensure complete and correct processingof all data. In these situations, it will often be necessary to employ CAATs.

d) Auditing with the computer

Auditing with the computer refers to the use of CAATs to assist in auditing work.

CAATs consist of audit software and test data which we will look at in detailbelow.

8.4.2 .Advantages and disadvantages of CAATs

a) The advantages of using CAATs

• Audit testing capability is increased – large volumes, up to 100%,

of information can be tested, thereby reducing or even eliminating

sampling risk.

• Tasks which are manually impossible can be carried out – using the

computer to trace key controls and processes where there is no visible

audit trail.

• Cost-effectiveness – although up-front costs may be considerable,

CAATs can often be used again in subsequent audits.

• Repetitive work is eliminated – this can increase job satisfaction for

auditors and for them up to apply professional judgment to key areas.

• Knowledge of client’s systems is improved – this is an important by-

product that enhances the auditor’s knowledge of the client and aids

future audit planning.

• Results from CAATs can be compared with results from traditionaltesting – if the results correlate, overall confidence is increased.

b) The challenges or disadvantages associated with using CAATs

• Setting up the software needed for CAATs can be time consuming andexpensive.

• Audit staff will need to be trained so they have a sufficient level of IT

knowledge to apply CAATs.

• Not all client’s systems will be compatible with the software used with

CAATs.

• There is a risk that the client’s data is corrupted and lost during the use

of CAATs.

• Information in real-time systems is constantly changing.

• Testing can be limited by the data held on the system.

• There is a risk of over-reliance on ‘infallible’ computerization of audit

procedures.• Auditor judgment must still be applied throughout the testing process.

8.4.3. Audit software

a) Meaning of audit software

Audit software is computer programs used by the auditor to interrogate a

client’s computer files. Audit software consists of computer programs used

by the auditors as part of their auditing procedures, to process data of audit

significance from the entity’s accounting system. It may consist of generalized

audit software or custom audit software. Audit software is used for substantiveprocedures.

Generalized audit software allows auditors to perform tests on computer files

and databases, such as reading and extracting data from a client’s systems for

further testing, selecting data that meets certain criteria, performing arithmetic

calculations on data, facilitating audit sampling and producing documents andreports quickly.

Customized audit software is written by auditors for specific tasks whengeneralized audit software cannot be used.

Using audit software, the auditor can scrutinize large volumes of data, andidentify results or anomalies which need further investigation.

Audit software performs the sort of tests on data that auditors might otherwise

have to perform by hand. The following are some examples of the use of auditsoftware in the course of an audit work.

b) Audit software: Examples of its use

• Access the client’s data files and obtain information without the need to

ask the client for information.

• Perform calculations and comparisons in analytical procedures.

• Sampling programs to extract data for audit testing, e.g. select a sample

of receivables for confirmation.

• Scan a file to ensure that all documents in a series have been accounted

for or to search for large and unusual items.

• Compare data elements in different files for agreement (e.g. prices on

sales invoices to authorized prices in master file).

• Re-perform calculations, e.g. totaling receivables ledger.

• Prepare documents and reports, e.g. Produce receivables’ confirmationletters and monthly statements.

The use of audit software is particularly appropriate during substantive testing

of transactions and especially balances. Interrogation software in particular can

help auditors prepare tests, by for example selecting a sample of balances or

dividing populations according to set criteria such as amounts owed (this iscalled stratification and is discussed further later in this unit).

Interrogation software can also help auditors scrutinize large volumes of data,and concentrate resources on the investigation of results.

Earlier we looked at the advantages and disadvantages of CAATs in general

and, although some may be similar, we will now look specifically at the benefitsof audit software along with the potential difficulties of using audit software.

c) Benefits and difficulties of using audit software

• Benefits of using audit software

– Audit software can perform calculations and comparisons morequickly than those done manually.

– Audit software makes it possible to test more transactions than when

simply manually scanning print outs. For example: audit software

may facilitate searches for exceptions, such as negative or very high

quantities when auditing inventory listings. The additional information

will give the auditor increased comfort that the figure being audited isreasonably stated.

– Audit software may allow the actual computer files (the source files)

to be tested from the originating program, rather than print outs from

spool or previewed files which are dependent on other software (and

therefore could contain errors or could have been tampered withfollowing export).

– Using audit software is likely to be cost-effective in the long-term ifthe client does not change its systems.

• Difficulties of using audit software

– The costs of designing tests using audit software can be substantial

as a great deal of planning time will be needed in order to gain an

in-depth understanding of the client’s systems so that appropriatesoftware can be produced.

– The audit costs in general may increase because experienced and

specially trained staff will be required to design the software, performthe testing and review the results of the testing.

– If errors are made in the design of the audit software, audit time, and

hence costs, can be wasted in investigating anomalies that have

arisen because of flaws in how the software was put together ratherthan by errors in the client’s processing.

– If audit software has been designed to carry out procedures during

live running of the client’s system, there is a risk that this disrupts the

client’s systems. If the procedures are to be run when the system is

not live, extra costs will be incurred by carrying out procedures to

verify that the version of the system being tested is identical to thatused by the client in live situations.

8.4.4. Test data

a) Meaning of test data

Test data is data submitted by the auditor for processing by the client’s computer

system, to test that the system processes the data as expected.

Test data techniques are used in conducting audit procedures by entering data

(e.g. a sample of transactions) into an entity’s computer system, and comparing

the results obtained with pre-determined results. Test data is used for tests ofcontrols.

An obvious way of seeing whether a system is processing data in the way that

it should be is to input some example, or test data and see what happens. The

expected results can be calculated in advance and then compared with theresults that actually arise. Test data has two aspects:

• Data representing valid transactions. Here the auditor is looking for

confirming that the system produces the required documentation suchas sales invoices and updates the accounting records.

• Data that is invalid for any reason. Here the auditors are reviewing

controls that prevent processing of data that is clearly wrong, negative

amounts or non-existent customers for example, or which breaches

limits set down by the company (for example transactions which take

credit customers over their credit limit). Auditors are interested in

seeing not only that the system rejects the transaction, but also thatbreaches are reported (by means of exception reports).

uses of test data

– Test data used to test specific controls in computer programs such ason-line password and data access controls.

– Test transactions selected from previously processed transactions

or created by the auditors to test specific processing characteristics

of an entity’s computer system. Such transactions are generally

processed separately from the entity’s normal processing. Test data

can, for example, be used to confirm whether the controls that prevent

the processing of invalid data are operating effectively, for example

by entering data with say a non-existent customer code or worth an

unreasonable amount, or a transaction which may if processed breakcustomer credit limits.

– Test transactions used in an integrated test facility. This is where a

‘dummy’ unit (e.g. a department or employee) is established, and to

which test transactions are posted during the normal processingcycle.

b) Benefits and problems of using test data

Bearing the examples above in mind, we can see the main benefits of using testdata techniques as follows:

– Test data provides evidence that the software or computer system

used by the client is working effectively by testing the program

controls and in some cases there may be no other way to test someprogram controls.

– Once the basic test data have been designed, the level of ongoing

time needed and costs incurred is likely to be relatively low until theclient’s systems change.

However, there are some problems with using test data as shown below:

– A significant problem with test data is that any resulting corruption of

data files has to be corrected. This is difficult with modern real-time

systems, which often have built-in (and highly desirable) controls to

ensure that data entered cannot be easily removed without leaving amark.

– Test data only tests the operation of the system at a single point of

time and therefore the results do not prove that the program was inuse throughout the period under review.

– Initial computer time and costs can be high and the client may changetheir programs in subsequent years.

Application activity 8.4

1. Name two types of CAATs that are commonly used.

2. How CAATS may be used in audit execution?

3. Explain the use of audit software

4. Explain the benefits of using test data

5. Diferentiate the aspects of test data

6. State the main audit procedure used for gathering audit evidence

Skills lab activity 8

Accounting records/transactions from the school’s bursar, share withstudents the following:

1. Let students apply sampling techeniques to obtains samples

2. Guide students on how some sampling techeniques can increase ordeacrese the sample size.

End unit 8 assessment

1. Explain the challenges associated with using CAATs

2. Differentiate audit software from test data

3. Explain the qualities of an audit evidence

4. Differentiate statistical sampling from non-statistical sampling