UNIT 6: AUDITOR’S REGULATION AND ETHICS

Key unit competence: To be able to comply with auditor’s regulation

and professional ethics.

Introductory activity

Financial and ethical reporting plays a significant role in sustainable

commercial development, as it provides the information required to assess

sustainable performance. In recent times, sustainability reporting has

constantly increased and is now a common business practice.

The countries that set the financial and ethical standards. However, the recent

role of emerging and developing nations requires that other regulations be

devised regarding not only financial stability but also inclusiveness and

economic development.

Because of the maturity of the institutional financial system and the efficient

market mechanism, the countries suggested reasons for international

differences concerning the context of financial reporting. This highlights the

importance of the auditing profession regaining and retaining the confidence

of the public, with duties performed in alignment with public interests.

Question

What would be the international standards adopted to support all contextsof auditing?

6.1. International auditing standards

Learning activity 6.1

Look the picture above, and answer the following questions:

1. What do you see in this picture?2. Which elements do you see that can be used as auditing standards?

O ACCOUNTING

Auditing | Student Book | Senior Six | Experimental version 75

6.1. International auditing standards

Look the picture above, and answer the following questions:

1. What do you see in this picture?

2. Which elements do you see that can be used as auditing standards?

Learning activity 6.1

6.1.1. The role of International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board

International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) are set by the International Auditing

and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), a technical committee of theInternational Federation of Accountants (IFAC).

The IAASB is there to serve the public interest by setting high-quality

international standards for auditing, quality control, review, other assurance,

and related services, and by facilitating the convergence of international and

national standards. In doing so, the IAASB enhances the quality and uniformity

of practice throughout the world and strengthens public confidence in the globalauditing and assurance profession.

Auditors are subject to ethical requirements imposed by their professional

bodies. One area where clients’ requirements may conflict with the requirements

for auditors to act ethically is whether the auditor should keep the affairs of

clients’ secret, or disclose them to others without obtaining the clients’consent.

The auditor should comply with the code of ethics for professional accountantsissued by the International Federation of Accountants.

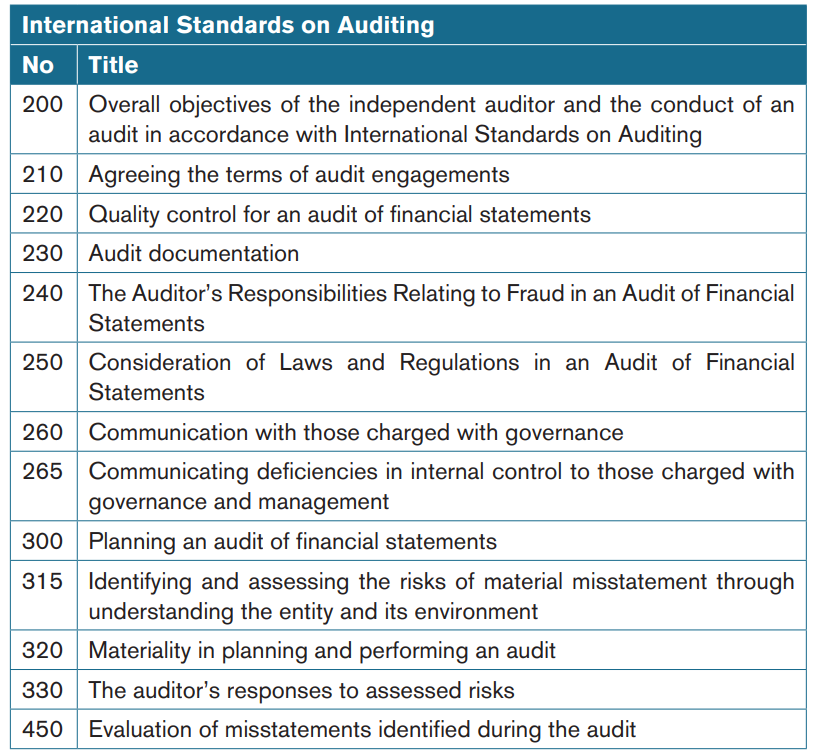

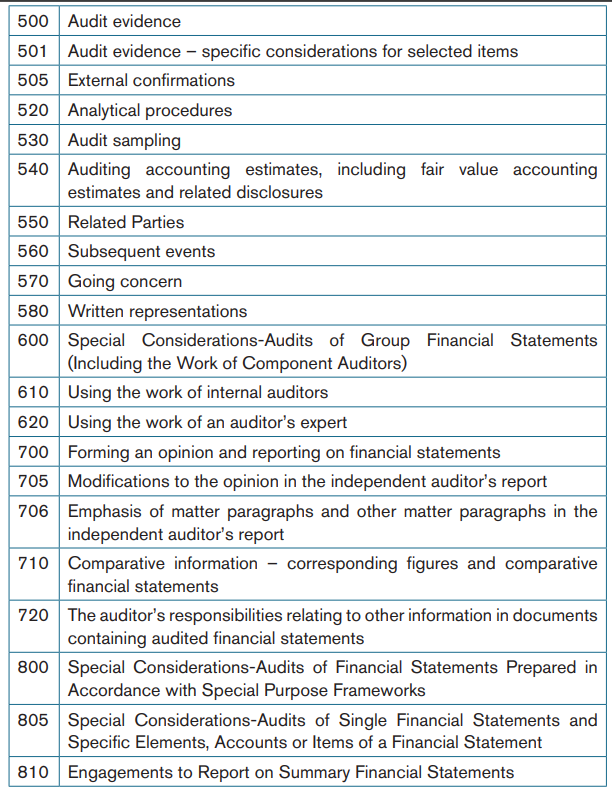

6.1.2. International Standards on Auditing (ISA)

International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) are set by the International Auditing

and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), a technical committee of the

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). ISAs are produced by IAASB, a

technical committee of IFAC. IAASB also produces other items of international

guidance, such as the International Standard on Quality Control (ISQC).

The IAASB selects subjects for detailed study by way of a subcommittee

established for that purpose. As a result of that study, an exposure draft is

prepared for consideration by the IAASB. If approved, the exposure draft is widely

distributed for comment by auditor bodies of IFAC, and to such internationalorganisations that have an interest in auditing standards.

The key standards issued by the IAASB include:

Respective responsibilities, Audit planning, Internal control, Audit evidence,Using work of other experts, Audit conclusions and audit report

6.1.3. The regulation of auditors

The accounting and auditing profession varies in structure from country to

country. In some countries, accountants and auditors are subject to strictlegislative regulation, while in others the profession is allowed to regulate itself.

Regulations governing auditors will, in most countries, be most important at the

national level. International regulation, however, can play a major part by:

• Setting minimum standards and requirements for auditors;

• Providing guidance for those countries without a well-developed

national regulatory framework;

• Aiding intra-country recognition of professional accountancyqualifications.

The audit regulations are:

• Statutory regulation

• Licensing of auditors

• Delegated regulation by professional bodies within a legal framework(not self- regulation)

Regulatory mechanisms are:

• Statutory audit requirement

• Legal provisions on appointment and dismissal of auditors,

• Licensing of auditors

• Competence requirements

• Professional conduct rules

• Auditing standards

• Disciplinary procedures• Governance rules for regulatory bodies

The regulation of audit is centrally concerned with the issue of ensuring that

auditors follow best practice standards in conducting the audit, and are

competent and independent; all of this being seen as essential in terms of

auditors’ capability to detect significant errors/omissions in financial statementsand to report faithfully on them.

Application activity 6.1

1. What is IFAC in full?

2. What are the key standards issued by the ISA?

3. What are the purposes of International Standards on Auditing number500 and 570

6.2. The fundamental principles of auditing

Learning activity 6.2

Look at the picture above and answer the following questions:

1. What are the activities carried out by the above persons?2. Tell me about a time you faced an ethical dilemma.

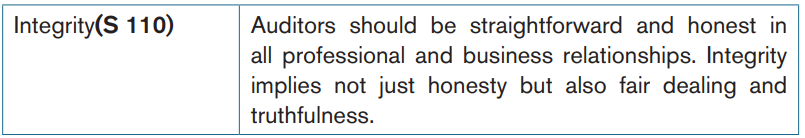

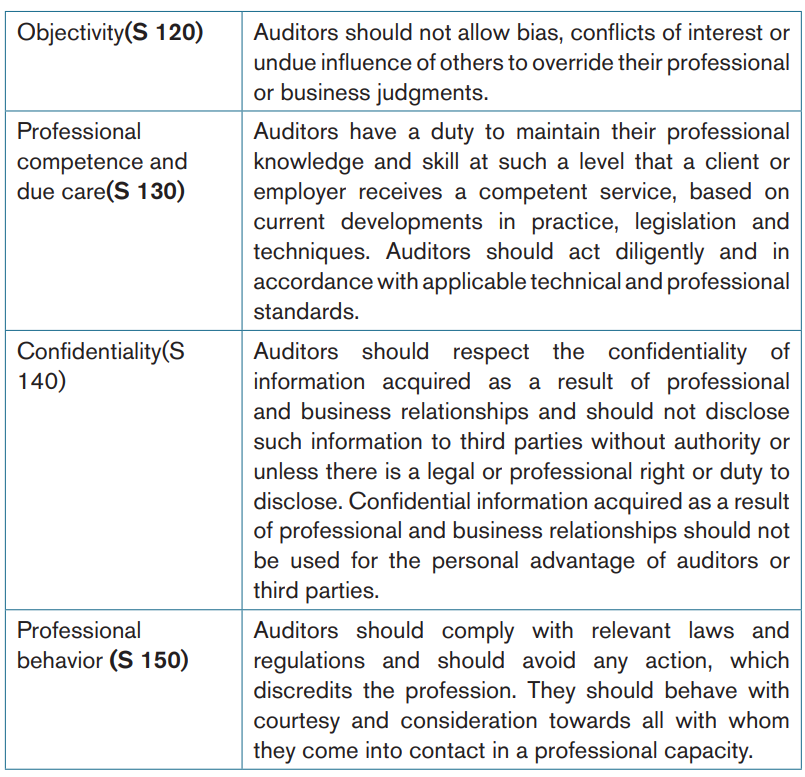

6.2.1. The fundamental principles of auditing as per IESBA

The IESBA Code of Ethics provides ethical guidance. The five fundamental

principles of ethics are as follows: integrity, objectivity, professionalcompetence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour.

The IESBA Code of Ethics states that independence requires independence

of mind and independence in appearance. In other words, the auditor mustbe, and must be seen to be, independent.

Independence of mind is the state of mind that permits the provision of a

conclusion without being affected by influences that compromise professional

judgement, allowing an individual to act with integrity, and exercise objectivityand professional scepticism.

Independence in appearance is the avoidance of facts and circumstances

that are so significant a reasonable and informed third party would be likely

to conclude that a firm’s, or audit and assurance team members, integrity,objectivity or professional scepticism have been compromised.

It is very important that the auditor is impartial and independent of management,

so that he/she can give an objective view on the financial statements of an

entity. The onus is always on the auditor not only to be independent but also

to be seen to be independent. You will see that some situations will constitute

such a significant threat to independence that an audit practice should not actas auditors if they arise.

The following examples of specific threats to independence are givenin the code

• Self-interest threats

There are many examples of a self-interest threat arising in the Code. They fallinto two general areas:

– Relationships

Close relationships between audit staff and employees of audit clients can lead

to a lack of independence if the interests of the audit firm and client become too

closely aligned and audit staff lose objectivity. Close relationships also causefamiliarity threats.

Examples of such self-interest threats are when:

• The audit firm has a financial interest in an audit client;

• Business relations between the firm and client are too close;

• Audit staff move to work at the audit client;

• The audit partner sits on the client board;

• There are family/personal relationships between audit staff/client;

• Audit staff are offered gifts/hospitality by client staff;

• Audit fees from a single client are a high percentage of the audit firm’s

total fees;

• The audit firm, or an individual on the audit engagement, enters a loan

or guarantee arrangement with a client (that is not a bank or similarinstitution carrying out its normal commercial business).

If an auditor inherits shares in a client company, he/she should try and sell themas soon as possible, and keep the firm informed about what is going on.

Audit firms should not enter into close business relationships with clients other

than that of the audit itself. They should not have joint ventures or joint marketingpolicies.

– Fee-related issues

An audit is carried out for a fee. However, self-interest threats arise if the fees

are so significant, or potentially so, that the audit firm loses its objectivity in

relation to the audit client. A key area is the proportion of total audit firm income

derived from a client. If it is too high, it indicates that the audit firm relies on thataudit client too much to be independent.

Contingent fee arrangements are prohibited for audit or assurance

engagements. Contingent fees are payable on condition of a favourable outcome

being achieved. For example, a firm may charge a client seeking a listing on thestock exchange a contingent fee which is payable if the listing is successful.

• Self-review threats

If an auditor audits work he/she has carried out for a client, he/she is unlikely tobe able to be objective about it.

There are two general circumstances in which this situation might arise:

If the audit staff member has recently worked for the audit client, or if the auditfirm carries out more than audit for the audit client.

– Recent service at audit client

Individuals who have been a director or officer of the client, or an employee

in a position to exert significant influence over the preparation of the client’s

accounting records or the financial statements on which the firm will express anopinion should not be assigned to the assurance team.

If an individual had been closely involved with the client before the period

covered by the auditor’s report, the audit firm should consider the threat toindependence arising and apply appropriate safeguards.

– Other services

Audit firms often offer a host of services other than audit. Examples include

preparing accounts and financial statements, valuation services, taxation services,

internal audit services, corporate finance services, IT services, temporary staff

cover, recruitment services, litigation support and legal services. Some of these,

for example, the routine preparation of tax returns, are not perceived to threaten

independence; others, particularly where it seems that audit firm staff are actingon behalf of management, do affect independence.

Audit firms are not permitted to assume a management responsibility for the

client. Activities which would be considered management responsibility include:

– Setting policies and strategic direction;

– Hiring or dismissing employees;

– Directing and taking responsibility for the actions of the entity’s

employees

– Authorising transactions;

– Controlling or managing of bank accounts or investments;

– Deciding which recommendations of the firm or other third parties toimplement;

– Reporting to those charged with governance on behalf ofmanagement;

– Taking responsibility for the preparation and fair presentation of thefinancial statements;

– Taking responsibility for designing, implementing and maintaininginternal control.

Activities that are routine and administrative, or involve matters that are

insignificant, generally are deemed not to be a management responsibility

and are permitted by the IESBA Code. Firms should not prepare accounts or

financial statements for listed or public interest clients. For any client, assurancefirms are also not allowed to:

– Determine or change journal entries without client approval;

– Authorise or approve transactions;– Prepare source documents.

In addition, in relation to the other services listed above, auditors should not

provide a valuation of an item that is going to be material to financial statements,

they should not carry out transactions on the client’s behalf when doing corporatefinance work, and should not underwrite the client’s shares.

Even if the services do not pose a threat to independence in themselves,

independence might be threatened if the auditor carried out a lot of other services

for a client, or if circumstances made the audit firm appear not independent.This will often be a matter of judgement for audit firms.

• Advocacy threat

If an audit firm is asked (or perceived) to promote their client or represent them,

for example in a legal claim, then the auditor would be biased in favour of theirclient and would not be able to be objective.

This loss of objectivity gives rise to an advocacy threat.

Examples of circumstances that create advocacy threats include:

– The auditor provides legal support to an audit client in a legal dispute;

– The auditor acts as an advocate on behalf of an audit client in a

dispute with a third party such as a tax disputes;

– The audit firm promotes shares in an audit client;

– The audit firm pitches a client reconstruction to a bank whilst

undertaking corporate finance services;

– A partner or employee of the audit firm serves as a director or officerof an audit client.

The audit firm should ensure it does not accept work likely to cause an advocacy

threat, and it should withdraw from an engagement if the risk to independencebecomes too high.

• Familiarity threat

We have already looked at the potential problems caused by relationships

between audit firm/staff and audit client/staff. These also cause a familiarity

threat, when audit staff become too familiar with a client, which causes them to

lose objectivity, and professional scepticism. Another familiarity threat is long

association, where an audit firm or its personnel have been involved in the auditof a particular client over an extended period. This can also affect objectivity.

For the audit of private limited companies, this is an issue for audit firms to monitor

themselves and take steps to avoid. The IESBA rules are more prescriptive inrelation to public limited companies.

• Intimidation threats

An intimidation threat arises when a member of the audit team is deterred from

acting objectively by threats (whether actual or perceived) from the directors,

officers or employees of an audit client. Such a threat may arise where the total

fees from an audit client represent a large proportion of the audit firm’s total

fees. Here the audit firm may be deemed to be dependent on the audit client

and this dependence may mean that they are more likely to give in to any threatsfor fear of losing the audit client.

Similarly, an intimidation threat is created when an audit client threatens the firm

with litigation or takes legal action against them. In this situation the relationship

between client management and members of the audit team can no longer be

characterised by complete candour and full disclosure and therefore the audit

firm should stand down as auditors as the threat would be too significant toavoid by other means.

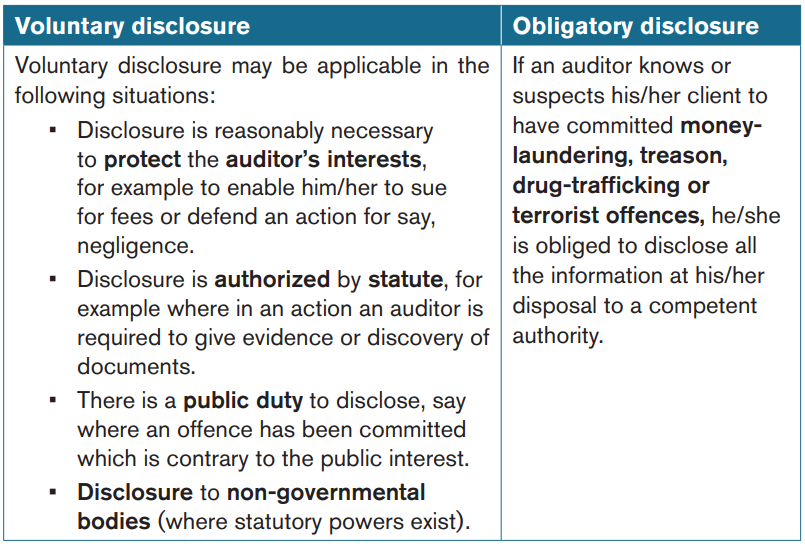

6.2.2. The professional duty of confidentiality

“Auditors have a professional duty of confidentiality. However, they may be

compelled by law, or consider it desirable in the public interest, to disclosedetails of clients’ affairs to third parties.”

Confidentiality requires auditors to refrain from disclosing information acquiredin the course of professional work except where:

– Consent has been obtained from the client, employer or otherproper source or;

– There is a public duty to disclose, or;

– There is a legal or professional right or duty to disclose.

The auditor agrees to serve a client in a professional capacity both the auditor

and the client should be aware that it is an implied term of that agreement that

the auditor will not disclose the client’s affairs to any other person with the

client’s consent or within the terms of certain recognised exceptions, which fallunder obligatory and voluntary disclosures.

The auditors must first obtain an understanding of the non-compliance and

disclose it to management. The client should be advised to report the non-compliance.

If they do not do so then the auditors may report the matters

themselves, but they are not obliged to do so. The recognised exceptions to theduty of confidentiality are as follows:

Application activity 6.2

1. Why an auditor should observe the professional ethics of integrity?

2. What will happen if an auditor knows or suspects his/her client tohave committed money-laundering or terrorist offences?

Skills lab activity 6

By carrying out research,students in their learning teams, identify the area(audit process) where each of the standard would be applied and why

End unit 6 assessment

1. Explain the concept of objectivity with reference to external auditors,and outline five general threats to objectivity.

2. What is the principle of objectivity?

3. Describe the review process that firms should adopt to ensure thatthey have maintained independence.

4. When is an auditor:

a) Obliged

b) Allowedc) To make disclosure of clients’ affairs to third parties?

5. In which of the following situations is it not appropriate to disclose

confidential information?

a) Client has granted permission

b) To obtain evidence about an item in financial statements

c) To fulfil a public dutyd) To fulfil a legal duty to disclose

6. Which of the following is not a fundamental principle of professional

ethics?

a) Independence

b) Integrity

c) Objectivityd) Confidentiality

7. It is important that an auditor’s independence is not questionable,

and that he/she should behave with integrity and objectivity in all

professional and business relationships. The following are a series

of questions, which were asked by auditors at a recent update

seminar on professional ethics.

a) A B & Co, the previous auditors, will not give my firm professional

clearance or the usual handover information because it is still

owed fees. Should I accept the client’s offer of appointment?

b) Can I prepare the financial statements of a company and remainas auditor?

Required:

Discuss the answers you would give to the above questions posed by theauditors based on IESBA Code of Ethics.