UNIT 4: BURN CONDITIONS

Key Unit competence

Take appropriate decision on Burn conditions

Introductory activity 4.0

Observe carefully the following images and answer to the questions below.

1. What do you think happened to this person in image A?

2. How do you call this condition in image A?

3. According the images above B and C, what do you think were the possible causes and risks factors that may contribute to this condition?

4. By analysing the image D, what do you think they are doing to this patient?

5. What do you think may be the complications for patient in image A?

4.1 Description of burn condition

Learning Activity 4.1

Judy A. is 32-year-old female, and she is an old case of epileptic condition on treatment at the nearest health center. He was cooking food for family in her kitchen when he turns on the bottle of cooking gas, she felt down. The entire house was engulfed in flames when the fire department arrived on scene. The neighbour called 911 when he smelt smoke. Judy was found conscious by the firefighters and was pulled out. She was burned on the anterior part of the chest with blisters formation which burst and involvement of the right upper limb. She was immediately stabilized on scene and was rushed to the nearest health center via ambulance. While enroute, the nurse started an 18-gauge IV with Ringer lactate and a dose of 5mg of Pethidine was given as pain killer. Upon arrival at the health center, Judy was found to have stage 2 burn wounds on his anterior part of the chest and entire right arm with stage 2 burns. Emergency treatment was provided: Local wound care with normal saline and aseptic dressing with Vaseline gauze was applied. Judy was at risk for smoke inhalation and a compromised airway as she presented a difficulty in breathing with tachypnea, so oxygen supplement with facial mask and fluid resuscitation was initiated before being transferred at the District hospital.

Questions related to the case study.

1. From the case study above, identify the risk factors that can be associated with burn injury

2. Explain the pathophysiological mechanisms behind blisters formation

3. List the signs and symptoms of burn as described in the case study.

4. From the signs described in the case study, why Judy is classified as stage 2 burn?

5. From the case scenario, what are the treatment offered to Judy before being transferred to District Hospital?

4.1. 1 Definition of Burn

Burn is a generic term used to describe cutaneous injury resulting from thermal, chemical, or electrical environmental causes. Pulmonary injury, both primary and secondary, is common and often necessitates ventilator support.

Burn is a tissue injury that results from thermal application (hot/ cold) and from application of physical or chemical energy urns disrupt the skin, which leads to increased fluid loss; infection; hypothermia; scarring; compromised immunity; and changes in body function, appearance, and body image.

It can lead to an increased morbidity and mortality rate in young children and the elderly when compared to other age groups with similar injuries.

4.1.2 Causes and Pathophysiology of Burn

Burns are caused by a transfer of energy from a heat source to the body. It may be caused several factors like dry heat, moist heat, cold injury, chemical burns, electrical burns, ionizing radiation and friction. The resulting effects are influenced by the temperature of the burning agent, duration of contact time, and type of injured tissue

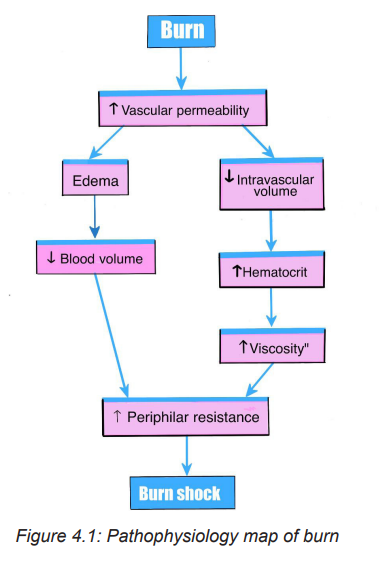

It is a crucial to understand the pathophysiology of a burn injury for effective management. Causes lead to different injury patterns, which require different management. Pathophysiologically, burn injuries result in both local and systemic responses. In addition to cutaneous injury, burns are often associated with smoke inhalation injury or other traumatic injuries that aggravate the local and systemic problems of burns.

Local response: The three zones of a burn were described by Jackson in 1947.

– Zone of coagulation: This occurs at the point of maximum damage. In this zone there is irreversible tissue loss due to coagulation of the constituent proteins.

– Zone of stasis: The surrounding zone of stasis is characterized by decreased tissue perfusion. The tissue in this zone is potentially salvageable. The main aim of burns resuscitation is to increase tissue perfusion here and prevent any damage becoming irreversible. Additional insults such as prolonged hypotension, infection, or edema can convert this zone into an area of complete tissue loss.

– Zone of hyperaemia: In this outermost zone tissue perfusion is increased. The tissue here will invariably recover unless there is severe sepsis or prolonged hypoperfusion.

These three zones of a burn are three dimensional, and loss of tissue in the zone of stasis will lead to the wound deepening as well as widening.

Systemic response: The release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators at the site of injury has a systemic effect once the burn reaches 30% of total body surface area. Cardiovascular changes like capillary permeability is increased, leading to loss of intravascular proteins and fluids into the interstitial compartment. Peripheral and splanchnic vasoconstriction occurs.

4.1.3 Types of Burn Burn type is determined according to the causative agent:

– Thermal Burns: caused by flame, flash, scald, or contact with hot or high cold objets

– Chemical Burns : result of contact with acids, alkalis, and organic compound

– Electrical: result from the conversion of electrical energy into heat. Extent of injury depends on the type of current, the pathway of flow, local tissue resistance, and duration of contact

– Radiation: result from radiant energy being transferred to the body resulting in production of cellular toxins

– Smoke and Inhalation Injury: from breathing hot air or noxious chemicals

4.1.4: Signs and symptoms of burns

Symptoms range from a feeling of minor discomfort to a life-threatening emergency, depending on the size and depth (degree) of the burn. Clinical symptoms of burn may differ also depending on the causative agent.

The patient with severe burns is likely to be in shock from hypovolemia. Frequently the areas of full-thickness and deep partial-thickness burns are initially anesthetic because the nerve endings have been destroyed.

Superficial to moderate partial thickness burns are very painful. Blisters, filled with fluid and protein, are common in partial-thickness burns. The patient with a larger burn area may develop a paralytic ileus, with absent or decreased bowel sounds. Shivering may occur as a result of chilling that is caused by heat loss, anxiety, or pain. The patient may be alert and able to answer questions shortly after admission or until he or she is intubated (if there is an inhalation injury).

Patients are often frightened and benefit from a calm reassurances and simple explanations of what to expect as you provide care. Unconsciousness or altered mental status in a burn patient is usually not a result of the burn but of the hypoxia associated with smoke inhalation. Other possibilities include head trauma, substance abuse, or excessive amounts of sedation or pain medication.

4.1.5: Diagnostic modalities

Diagnosing burn injury is basically determined by the clinical symptoms a patient is presenting at time of admission. Basic laboratory studies should be obtained in patients with severe burns or concomitant trauma, including a complete blood count, blood type and cross match, chemistries electrolytes measurement, coagulation profiles, arterial blood gas measurement, and a pregnancy test, when appropriate.

Laboratory tests or changes in laboratory values such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) level are of low yield in detecting or predicting burn infections because of the inflammatory response associated with the burn itself .Renal function tests like creatinine and albumin clearance should be carried out because burned patients are at high risks of renal complication resulting from hypovolemic shock.

4.2 Classification of burns injury

The treatment of burns is related to the severity of the injury .Severity of burn is determined by:

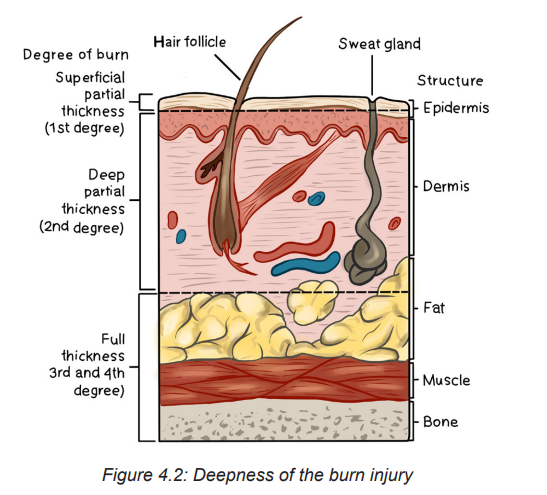

1. Depth of burn: Burn injury involves the destruction of the integumentary system (epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue). The depth of a burn injury depends on the type of injury, causative agent, temperature of the burn agent, duration of contact with the agent, and the skin thickness. Burns are classified according to the depth of tissue destruction.

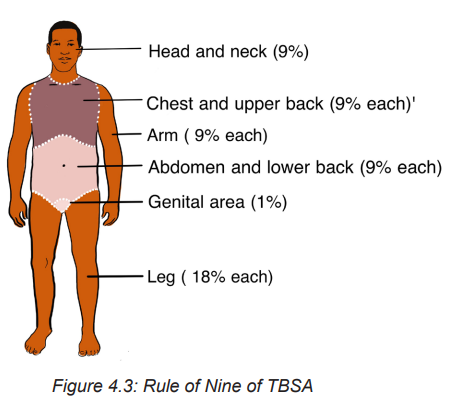

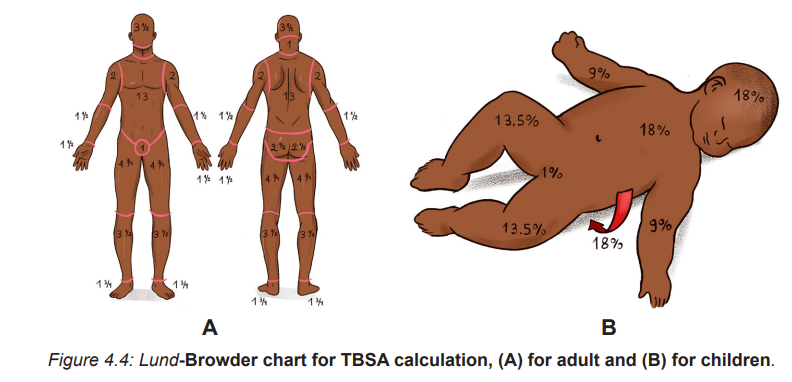

2. The extent of burn calculated in percent of total body surface area (TBSA): Two commonly used guides for determining the TBSA affected

Lund-Browder: more accurate because it considers the patient’s age in proportion to relative body-area size

The Rule of Nines: is often used for initial assessment of a burn patient because it is easy to remember.

Note: Depending to extent and deepness of injured tissue, burn is classified in 3 different stages

First-degree Burns or Superficial burns: involve only the first layer of the skin (epidermis) and characterized by redness, manifests with erythema and tenderness. Healing occurs naturally within a week.

– Second degree burn or partial thickness: This involves part of dermis. It manifests with blisters, edema, moist surface and pain at the affected site.

– Third-degree Burns or Full thickness: Third-degree burns involve all layers of the skin and may be some damage to the nerves, fat tissue, muscles and bones .The skin may vary from white and lifeless to black and charred. White or greyish and the surface is pain free

3. Location of burn: The severity of the burn injury is also determined by the location of the burn wound. Burns to the face and neck and circumferential burns to the chest or back may interfere with breathing as a result of mechanical obstruction from edema or leathery, devitalized burn tissue (eschar). These burns may also indicate possible inhalation injury and respiratory mucosal damage.

Burns to the hands, feet, joints, and eyes are of concern because they make self-care difficult and may jeopardize future function. Burns to the hands and feet are challenging to manage because of superficial vascular and nerve supply systems that need to be protected while the burn wounds are healing. Burns to the ears and the nose are susceptible to infection because of poor blood supply to the cartilage. Burns to the buttocks or perineum are highly susceptible to infection from urine or feces contamination

Circumferential burns to the extremities can cause circulation problems distal to the burn, with possible nerve damage to the affected extremity. Patients may also develop compartment syndrome from direct heat damage to the muscles, swelling, and/or pre-burn vascular problems

4. Patient risk factors (e.g., age, past medical history): patient with pre existing cardiovascular, respiratory, or renal disease has a poorer prognosis for recovery because of the tremendous demands placed on the body by a burn injury. The patient with diabetes mellitus or peripheral vascular disease is at high risk for poor wound healing, especially with foot and leg burns. General physical debilitation from any chronic disease, including alcoholism, drug abuse, or malnutrition, makes it challenging for the patient to fully recover from a burn injury. In addition, the burn patient who has also sustained fractures, head injuries, or other trauma has a more difficult time recovering.

4. 3 Calculation of the Total Body Surface Area (TBSA)

The TBSA is an other important factor to consider for effective management of burn injury. It is calculated by using two commonly used guides: (1) Lund-Browder: more accurate because it considers the patient’s age in proportion to relative body area size and (2) The Rule of Nines: often used for initial assessment of a burn patient because it is easy to remember.

4.3.1 The Rule of Nines or Wallace rule The size of a burn can be quickly estimated by using the “rule of nines.” This method divides the body’s surface area into percentages.

– The front and back of the head and neck equal 9% of the body’s surface area.

– The front and back of each arm and hand equal 9% of the body’s surface area.

– The chest equals 9% and the stomach equals 9% of the body’s surface area.

– The upper back equals 9% and the lower back equals 9% of the body’s surface area.

– The front and back of each leg and foot equal 18% of the body’s surface area.

– The genital area equals 1% of the body’s surface area.

4.3.2: Lund and Browder chart

The Lund and Browder chart is a tool useful in the management of burns for estimating the total body surface area affected. This chart takes into consideration of age of the person, with decreasing percentage Burned Surface Area (BSA) for the head and increasing percentage BSA for the legs as the child ages, making it more useful in paediatric burns.

Self-assessment activity 4.1

1. Basing on the stage of burn, describe the clinical symptoms of burn

2. What is the common and easiest clinical guides for calculating TBSA in burned patient?

3. Provide the difference among the 3 stages of burn injury.

4.4 Treatment and phases of burn management

Burn management can be organized chronologically into three phases: emergent (resuscitative), acute (wound healing), and rehabilitative (restorative). Overlap in care does exist. For example, the emergence phase begins at the time of the burn injury, and care often begins in the prehospital phase, depending on the skill level of providers at the scene. Planning for rehabilitation begins on the day of the burn injury or admission to the burn center. Formal rehabilitation begins as soon as functional assessments can be performed. Wound care is the primary focus of the acute phase, but wound care also takes place in both the emergent and rehabilitation phases.

The four major goals relating to burn management are (1) Prevention measures, (2) life-saving measures for the severely burned person (3) prevention of disability and disfigurement and (4) rehabilitation.

4.4.1 Prehospital care

At the scene of the injury, priority is given to removing the person from the source of the burn and stopping the burning process. Rescuers must also protect themselves from being injured. In the case of electrical and chemical injuries, initial management involves removal of the patient from contact with the electrical or chemical source.

Small thermal burns (10% or less of TBSA) should be covered with a clean, cool, tap water dampened towel for the patient’s comfort and protection until medical care is available. Cooling of the injured area (if small) within 1 minute helps minimize the depth of the injury. If the burn is large (greater than 10% TBSA) or an electrical or inhalation burn is suspected, first focus your attention on the ABCs:

– Airway: Check for patency, soot around nares and on the tongue, singed nasal hair, darkened oral or nasal membranes.

– Breathing: Check for adequacy of ventilation.

– Circulation: Check for presence and regularity of pulses, and elevate the burned limb(s) above the heart to decrease pain and swelling.

To prevent hypothermia, cool large burns for no more than 10 minutes. Do not immerse the burned body part in cool water because it may cause extensive heat loss. Never cover a burn with ice, since this can cause hypothermia and vasoconstriction of blood vessels, thus further reducing blood flow to the injury. Gently remove as much burned clothing as possible to prevent further tissue damage. Leave adherent clothing in place until the patient is transferred to a hospital. Wrap the patient in a dry, clean sheet or blanket to prevent further contamination of the wound and to provide warmth.

Chemical burns are best treated by quickly removing any chemical particles or powder from the skin. Remove all clothing containing the chemical because the burning process continues while the chemical is in contact with the skin. Flush the affected area with copious amounts of water to irrigate the skin anywhere from 20 minutes to 2 hours post exposure. Tap water is acceptable for flushing eyes exposed to chemicals. Tissue destruction may continue for up to 72 hours after contact with some chemicals

Observe patients with inhalation injuries closely for signs of respiratory distress .These patients need to be treated quickly and efficiently if they are to survive. If CO poisoning is suspected, treat the patient with 100% humidified O2. Patients who have both body burns and an inhalation injury must be transferred to the nearest burn center.

Always remember that the burn patient may also have sustained other injuries that could take priority over the burn itself. Individuals involved in the prehospital phase of burn care must adequately communicate the circumstances of the injury to hospital providers. This is especially important when the patient’s injury involves being trapped in a closed space, exposure to hazardous chemicals or electricity or a possible traumatic injury.

4.4.2 Emergent phase/ Resuscitative phase

The emergent or resuscitative phase is the time required to resolve the immediate, life-threatening problems resulting from the burn injury. This phase usually lasts up to 72 hours from the time the burn occurred. The primary concerns are the onset of hypovolemic hock and edema formation. The emergent phase ends when fluid mobilization and diuresis begin.

In the emergent phase, the patient’s survival depends on rapid and thorough assessment and appropriate interventions. Usually the physician and you make an initial assessment of the depth and extent of the burn and coordinate the actions of others on the health care team. In a community hospital, determine whether the patient requires inpatient or outpatient care. In the case of inpatient care, decide whether the patient remains in the hospital or should be transferred to the closest burn center. Nursing and collaborative management predominantly consists of airway management, fluid therapy, and wound care. Patients often improve and worsen, unpredictably, on an almost daily basis. Physical and occupational therapy are important in both the acute and rehabilitation phases, proper positioning and splinting begin on the day of admission. Emotional support and teaching of patients and caregivers begin on admission.

• Airway management

Respiratory support with early endotracheal intubation if necessary in which ventilator support will be used with the delivered oxygen concentration based on Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) values. Escharotomies of the chest wall may be needed to relieve respiratory distress secondary to circumferential, fullthickness burns of the neck and trunk .When intubation is not performed, treatment of inhalation injury includes administration of 100% humidified O2 as needed.

Place the patient in a high Fowler’s position, unless contra indicated (e. g: spinal injury), and encourage deep breathing and coughing every hour. Reposition the patient every 1 to 2 hours and provide suctioning and chest physiotherapy (as ordered). When intubation is not performed, 100% humidified O2 as needed. The CO poisoning is treated by administering 100% O2until carboxyhemoglobin levels return to normal.

• Fluid therapy

The ideal resuscitation fluid should be one that produces a predictable and sustained increase in intravascular volume, has a chemical composition as close as possible to that of extracellular fluid, is metabolized and completely excreted without accumulation in tissues, does not produce adverse metabolic or systemic effects, and is cost-effective in terms of improving patient outcomes. Currently, there is no such fluid available for clinical use.

Establishing intravenous (IV) access is critical for fluid resuscitation and drug administration. At least two large-bore IV access sites must be in place for patients with burns that are 15% TBSA or more. It is critical to establish IV access that can handle large volumes of fluid. For patients with burns greater than 30% TBSA, consider a central line for fluid and drug administration and blood sampling .An arterial line is often placed if frequent ABGs or invasive BP

– Assess the extent of the burn wound using a standardized Chart

– Then use a standardized formula to estimate the patient‘s fluid ressuscitation requirements.

– Fluid replacement is achieved with crystalloid solutions usually lactated Ringer’s, colloids like albumin, or a combination of the two.

– All formulas are estimates, and fluids must be titrated based on the patient’s response (e.g., hourly urine output, vital signs).

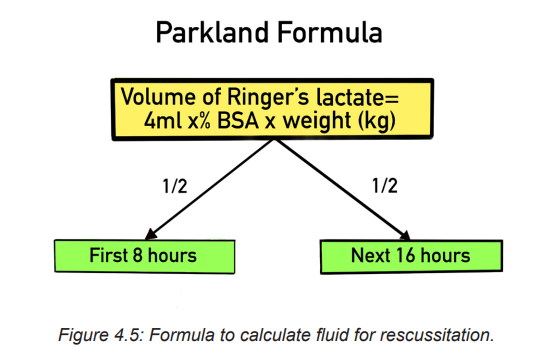

– The Parkland (Baxter) formula for fluid replacement is the most Common formula used

This formula was designed to help the healthcare provider determine the proper amount of fluids to administer to a patient following a burn. Parkland’s burn formula is most useful during the first twenty four hours of fluid resuscitation with second degree or greater burns. Ringers lactate is the fluid of choice and should be administered at 4 mL/kg of body weight per percentage of burn using total body surface area (TBSA) as a guide.

Administer ½ of fluid requirements in 1st 8 hours, then administer the 2nd half of fluid requirements over the next 16 hours.

For example :A person weighing 75 kg with burns to 20% of his or her body surface area would require 4 x 75 x 20 = 6,000 mL of fluid replacement within 24 hours. The first half of this amount is delivered within 8 hours from the burn incident, and the remaining fluid is delivered in the next 16 hours.

Children receive maintenance fluid in addition, at an hourly rate of:

– 4ml/kg for the first 10kg of body weight plus

– 2ml/kg for the second 10kg of body weight plus

– 1ml/kg for >20kg of body weight.

• Wound care

Once a patent airway, effective circulation, and adequate fluid replacement have been established, priority is given to care of the burn wound. Partial thickness burn wounds appear pink to cherry-red and are wet and shiny with serous exudate. In this principle, permanent skin coverage is the primary goal for burn wound care. Two approaches to burn wound treatment are (1) the open method and (2) the use of multiple dressing changes (closed method).

In the open method: the patient’s burn is covered with a topical antimicrobial and has no dressing over the wound.

In the multiple dressing change, or closed method, sterile gauze dressings are impregnated with or laid over a topical antimicrobial.

– These dressings are changed anywhere from every 12 to 24 hours to once every 14 days (depending on the product).

– Most burn centers support the concept of moist wound healing and use dressings to cover the burned areas, with the exception of facial burns.

– When the patient’s open burn wounds are exposed, always wear personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., disposable hats, masks, gowns, gloves).

– When removing contaminated dressings and washing the dirty wound, use nonsterile, disposable gloves.

– Use sterile gloves when applying ointments and sterile dressings

– In addition, prevent shivering by keeping the room warm (approximately 85° F [29.4° C]

– Perform thorough hand washing both before and after patient contact to prevent cross-contamination

– Permanent skin coverage is the primary goal for burn wound care: different forms of skin grafting will be used in case of needs.

• Drug therapy

– Provision of analgesics and sedatives: Promote the use of analgesics for the patient’s comfort. Early in the post burn period, IV pain medications should be given because (1) onset of action is fastest with this route; (2) oral medications have a slower onset of action and are not as effective when GI function is slowed or impaired because of shock or paralytic ileus; and (3) intramuscular (IM) injections will not be absorbed adequately in burned or oedematous areas, causing pooling of medications in the tissues. Analgesic requirements can vary widely from one patient to another, so consider a multimodal approach to pain management.

! Remember that the patient’s pain intensity may not directly correlate with the extent and depth of burn.

– Tetanus immunization: Tetanus toxoid is given routinely to all burn patients because of the likelihood of anaerobic burn wound contamination. If the patient has not received an active immunization within 10 years before the burn injury, tetanus immunoglobulin should be considered.

– Antimicrobial agents: After the wound is cleansed, topical antimicrobial agents may be applied and covered with a light dressing. Systemic antibiotics are not routinely used to control burn wound flora because the burn eschar has little or no blood supply and consequently little antibiotic is delivered to the wound. In addition, the routine use of systemic antibiotics increases the chance of developing multidrug resistant organisms.

– Some topical burn agents penetrate the eschar and inhibit bacterial invasion of the wound. Silver impregnated dressings (e.g. Acticoat, Silverlon, Aquacel AG) can be left in place from 3 to 14 days, depending on the patient’s clinical situation and the particular product. Silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene, Flamazine) and mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon) creams are also used.

SAFETY ALERT:

Check the patient for any allergies to sulfa, since many burn antimicrobial creams contain sulfa

– Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (VTE): Burn patients are at risk for VTE. If there are no contraindications, it is recommended that low-molecular weight heparin or low-dose unfractionated heparin be started as soon as it is considered safe. For burn patients who have a high bleeding risk, VTE prophylaxis with sequential compression devices and/or graduated compression stockings are used until the bleeding

• Nutritional therapy

Once fluid replacement needs have been addressed, nutrition takes priority in the initial emergent phase. Early and aggressive nutritional support within several hours of the burn injury can decrease mortality risks and complications, optimize healing of the burn wound, and minimize the negative effects of hypermetabolism and catabolism. Enteral feedings (gastric or intestinal) have almost entirely replaced parenteral feeding. Early enteral feeding, usually with smaller-bore tubes, preserves GI function, increases intestinal blood flow, and promotes optimal conditions for wound healing

• Maintaining Normal Body Temperature

– Provide warm environment: use heat shield, space blanket, heat lights, or blankets.

– Assess body temperature frequently.

– Work quickly when dressing wounds to minimize heat loss from the wound

• Minimizing pain and anxiety

– Pain scale to assess pain and differentiate between restlessness due to pain and restlessness due to hypoxia.

– Administer analgesics as prescribed

– Provide emotional support, reassurance, and simple explanations about procedures.

– Assess patient and family understanding of burn injury

– Psychological interventions if necessary.

4.4.3. INTERMEDIATE PHASE

Begun from 48 to 72 hours after the burn injury and consist of:

– Routine care

– Restoring normal fluid balance

– Preventing Infection

– Maintaining adequate nutrition

– Promoting Skin Integrity

– Relieving pain and discomfort

– Promoting physical mobility

– Supporting patient and family processes

– Monitoring and managing potential complications

4.4.4 Rehabilitation phase

– Promoting activity tolerance

– Improving body image and self-concept

– Monitoring and managing potential complications

– Promoting activity tolerance

4. 5 Complications of burn

The three major organ systems most susceptible to complications during the emergent phase of burn injury are the cardiovascular, respiratory, and urinary systems.

Cardiovascular system complications: include dysrhythmias and hypovolemic shock, which, if untreated, may progress to irreversible shock. Circulation to the extremities can be severely impaired by deep circumferential burns and subsequent edema formation, which act like a tourniquet.

Respiratory system: is vulnerable to two types of injury: (1) upper airway burns and (2) lower airway injury. Upper airway distress may occur with or without smoke inhalation, and airway injury at either level may occur in the absence of burn injury to the skin. The patient may require a fiberoptic bronchoscopy and carboxyhemoglobin blood levels to confirm a suspected inhalation injury. Look in the prehospital notes to see if the patient was exposed to smoke or fumes.

Urinary System: The most common complication of the urinary system in the emergent phase is acute tubular necrosis (ATN). If patient becomes hypovolemic, blood flow to the kidneys is decreased, causing renal ischemia. If this continues, acute kidney injury may develop.

With full-thickness and major electrical burns, myoglobin (from muscle cell breakdown) and haemoglobin (from RBC breakdown) are released into the bloodstream and occlude renal tubules. Carefully monitor the adequacy of fluid replacement because this can counteract obstruction of the tubules.

Infection: The body’s first line of defense, the skin, is destroyed by a burn injury. The burn wound is now colonized with the person’s own organisms that were on the skin before the burn. Localized inflammation, induration, and sometimes suppuration can be seen at the burn wound margins. Partial-thickness burns can convert to full-thickness wounds when these organisms invade viable, adjacent, unburned tissue. Invasive wound infections may be treated with systemic antibiotics based on culture and sensitivity wound swab results.

Watch for signs and symptoms, including hypothermia or hyperthermia, increased heart and respiratory rate, decreased BP, and decreased urine output .The patient may have mild confusion, chills, malaise, and loss of appetite. The WBC count usually is between 10,000/µL (10 ×109/L) and 20,000/µL (20 ×109/L). The WBCs have functional defects and the patient remains immunosuppressed for many months after the burn injury

The causative organisms of sepsis are usually gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas, Proteus organisms), putting the patient at further risk for septic shock. When sepsis is suspected, immediately obtain cultures from all possible sources, including the burn wound, blood, urine, sputum, oropharynx and perineal regions, and IV site. Treatment immediately begins with antibiotics appropriate for the usual residual flora of the particular burn center. When the culture and sensitivity results are known, the antibiotic in use may be continued or changed based on the results. At this stage the patient’s condition is considered critical, requiring close monitoring of vital signs.

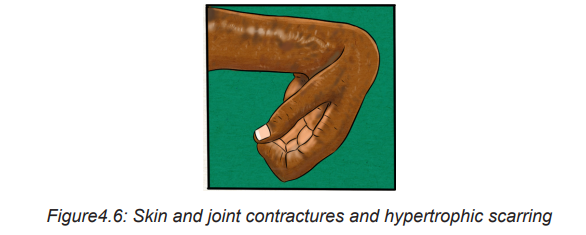

Skin and joint contractures and hypertrophic scarring: A contracture (an abnormal condition of a joint characterized by flexion and fixation) develops as a result of the shortening of scar tissue in the flexor tissues of a joint. Areas that are most susceptible to contracture formation include the anterior and lateral neck areas, axillae, antecubital fossae, fingers, groin areas, popliteal fossae, knees, and ankles.

Self-assessment activity 4.3

1. List the four major goals relating to burn management

2. What are the components of nursing and collaborative management of pain?

3. How can you calculate an estimated fluid replacement for a patient with burn?

4. As associated nurse how will you provide fluid to the patient once it is calculated

4.6 End unit assessment

End of unit assessment

1. The injury that is least likely to result in a full-thickness burn is

a. Sunburn.

b. Scald injury.

c. Chemical burn.

d. Electrical injury

2. When assessing a patient with a partial-thickness burn, the nurse would expect to find

a. Blisters.

b. Exposed fascia.

c. Exposed muscles.

d. Intact nerve endings.

e. Red, shiny, wet appearance.

3. Which one of the following is not most important factors that influencing the resulting effects of burn?

a. Temperature of the burning agent

b. Duration of contact time

c. Age of the victim

d. Type of injured tissue

4. The patient is being admitted at health facility where you are working as student in clinical placement and with he is presenting with burn injury after gas explosion at home. Which type of burn injury does the nurse expect to see on admission?

a. Chemical burn injury

b. Thermal burn injury

c. Electrical burn injury

d. Smoke and inhalation injury

5. Which of the following clinical symptoms is likely to explain the full thickness/ third- degree burns?

a. Fluid-filled vesicles or blisters formation associated to sever pain caused by nerve injury.

b. Erythema blanching on pressure, pain and mild swelling, novesicles or blisters

c. Superficial epidermal damage with hyperemia where tactile and pain sensation is intact

d. All skin elements and local nerve endings are destroyed and coagulation necrosis present.

6. You are caring XY patient of 50year old male who has suffered second and third degree burns to the entire anterior thorax and abdomen, anterior right arm, and the anterior of the left upper leg. By using the Rules of Nine, which one of the following constitute the best answer about TBSA:

a. 9%

b. 18%

c. 27%

d. 36%

7. Identify the 4 common factors determining the severity of burn?

8. What do you understand by circumferential burn?

9. By using Parkland formula, calculate the fluid replacement to be administered to a XY patient with TBSA of 32%. Mr XY is a 45 years old man with 1.80m of height and 75kg of weight

10. List at least 5 complications related to burn injury