UNIT 3: VITAL SIGNS AND PARAMETERS

Key unit competence:

Interprets correctly the measured vital signs and parametersIntroductory activity 3

PERSON A

1) By observing these pictures above, what do you think has happened to

the person A?

2) What can you conclude about the health condition of this injured person?

3) According to your observation, what do you think is the nurse doing to

the person A?

4) In your view, what do you think can happen to the person A in case

these actions being done by the nurse are not done?3.1. Introduction to vital signs

Learning activity 3.1.

Do searching of the Fundamentals of Nursing book and read the vital signs unit

and come up with a summary of the following:

1) Definition of vital signs

2) The cardinal vital signs

3) Times to assess the vital signs

4) Guidelines for vital signs assessmentVital signs are the fundamental measurements of life signs. The term vital signs

(VS) suggests assessment of vital or critical physiological functions. Vital signs

provide important information about the interrelationship between body systems.

The vital signs reflect changes in function that otherwise might not be observed.

Vital signs that are within normal limits reflect a person’s physiological wellbeing,

whereas abnormal vital signs may be an early warning of clinical deterioration.The cardinal vital signs are body temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood

pressure. Oxygen saturation is also commonly measured at the same time as the

traditional vital signs. An alteration in vital signs signals a change in physiological

function and the need for medical or nursing intervention.a) Uses of vital signs

Very often the vital signs are used: To establish the diagnoses of the patients:

The disruption of one or several vital signs can orient the diagnosis because it can

be the first sign of disease; to prescribe treatments and for medical follow-

up: They permit to have a control on the patient’s general state. That means that

they are used to evaluate the success of the implementation and good evolution of

prescribed treatment (recovery, relapse of the illness); and to establish nursing

care planb) Times(moments) to assess vital signs

When and how often to assess a specific patient’s vital signs are chiefly nursing

judgments, depending on the patient’s health status. A patient’s vital signs may be

recorded on a routine basis (every 8 hours for most hospitals), however if there is a

change in the patient’s condition then the vital signs may need to be recorded more

frequently depending on the physician orders or according to nurse judgment. Below,

are examples of times (moments) to assess vital signs though the list is not exhaustive: On admission to a health care facility

When a person has a change in health status or reports symptoms such as

chest pain or difficulty breathing.

Before, during and after surgery or an invasive procedure.

Before and/or after the administration of a medication that could affect the

respiratory or cardiovascular systems.

Before and after any nursing intervention that could affect the vital signs

(e.g. ambulating a person who has been on bed rest or when a person is

receiving a blood transfusion).

Following an incident, accident or injury in the health care setting (e.g. when

a person has fallen or has been administered an incorrect medication).c) Guidelines for assessing vital signs

Vital signs are part of the assessment data base. You include them in a complete

physical assessment or obtain them individually to assess a patient’s condition.

Establishing a database of vital signs during a routine physical examination serves

as a baseline for future assessments. Guidelines for assessment of vital signs

include:

Use of functional and appropriate equipment in regard to the size and age

of the patient.

Select equipment based on the patient’s condition and characteristics

Being familiar with normal ranges of vital signs for different ages.

Always compare the patient’s usual range of vital signs with later findings.

Determine the patient’s medical history, therapies, and prescribed

medications. Some illnesses or treatments cause predictable changes in

vital signs.

Control or minimize environmental factors that affect vital signs.

Use an organized, systematic approach when taking vital signs. Each

procedure requires a step-by-step approach to ensure accuracy.

Use vital sign measurements to determine indications for medication

administration. For example, give certain cardiac drugs only within a range

of pulse or BP values. Analyze the results of vital sign measurements. Vital signs are not interpreted

in isolation. You need to also know related physical signs or symptoms and

be aware of the patient’s ongoing health status.

Communicate significant changes in vital signs to the patient’s health care

provider or the charge nurse. Document findings and compare with baseline

measurements to identify significant changes.

Instruct the patient or family caregiver in vital sign assessment and the

significance of findings.

Vital sign measurements can require removing clothing or exposing areas.

Provide patient privacy while being sensitive to cultural norms w h e n

measuring vital signs.Vital signs serve different role. Vitals signs can orient the diagnosis because it can

be the first sign of disease. They are also used to evaluate response to intervention.Self-assessment 3.1.

1) List the vital signs you know

2) What do vital signs serve for?

3) What is the right time to measure the vital signs?

4) Why is it important for the nurse to know the patient’s usual range of

vital signs?3.2. Body temperature

3.2.1. Body temperature overviewLearning activity 3.2.1.

Use the provided book of Fundamentals of Nursing to read the materials on

body temperature under the vital signs unit and make a summary note of the

following:

1) Definition of body temperature

2) Difference between core and surface temperature

3) Normal values of body temperature

4) Factors affecting body temperature

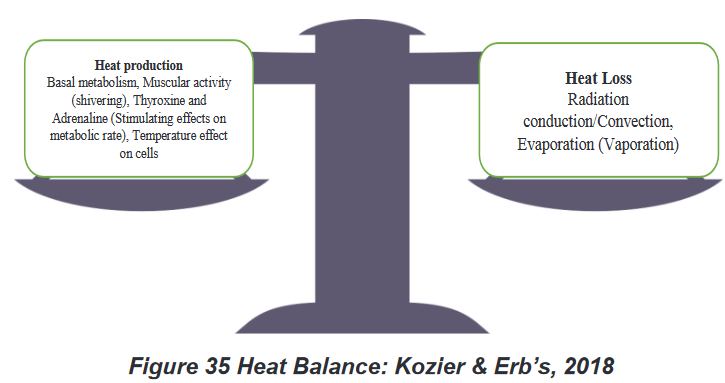

5) Routes of body temperature assessmenta. Concept of Body Temperature

Body temperature is defined as the balance between the heat produced by

the body and the heat lost from the body, measured in heat units called degrees

either Fahrenheit or Celsius. There are two kinds of body temperature: core

temperature and surface temperature. The core temperature which remains

relatively constant is the temperature of the deep tissues of the body, such as the

abdominal cavity and pelvic cavity. The surface temperature is the temperature

of the skin, the subcutaneous tissue, and fat. It rises and falls in response to the

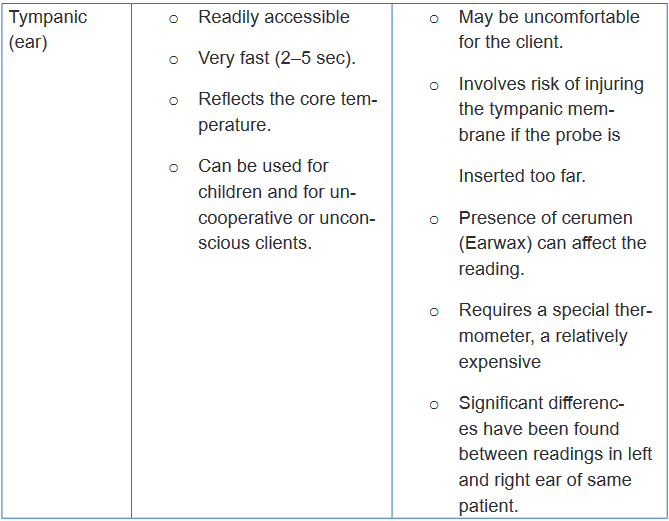

environment.The normal core body temperature is a range of temperatures. No single value

can be considered “normal” since the body temperature fluctuates as a result of

differences in metabolism. The normal range for adults is considered to be between

36°C and 37.5°C (96.8°F to 99.5°F) with the average being 98.6°F(37°C). The core

temperature is generally 1°F to 2°F (0.6°C to 1.2°C) higher than surface (skin)

temperature. This normal temperature range is maintained by keeping a balance

between heat production and heat loss.Box 3.2.

To convert Fahrenheit to Celsius: subtract 32 from Fahrenheit reading

and multiply by 5/9.

C=(F-32°)×5/9

Example104°-32°)×5/9=40°C

To convert Celsius to Fahrenheit: Multiply the Celsius reading by 9/5

and add 32.

F=(C×9/5)+32

Example: (40°C ×9/5)+32=104°F

b. Factors affecting body temperature

A variety of internal and external factors affect body temperature. Nurses should

be aware of physiological factors that affect a person’s body temperature so that

they can recognize normal temperature variations and understand the significance

of body temperature measurements that deviate from normal. The common

factors are environment, time of day, gender, age, physical activity and exercise,

medications, food or liquid intake, stress, and illness. Age: Infants have an immature thermoregulatory mechanism and their

temperature is greatly influenced by the environment and must be protected

from extreme changes. Elderly people have decreased thermoregulatory

controls and are also more sensitive to extremes of environmental temperature

changes. Elderly individuals are particularly at risk for hypothermia for a variety

of reasons, such as poor activity, limited metabolism and poor diet, as well

as poor temperature-regulating mechanisms. Many older people, particularly

those over 75 years old, are at risk of hypothermia (temperature below 360C) The action of hormones: At ovulation, a woman’s body temperature may

increase by about 0.30C to 0.60C, due to the influence of progesterone. Just prior

to ovulation the estrogen peak may cause a slight decrease in body temperature.

Thyroxin, adrenaline and noradrenalin all increase body temperature. Rest and sleep: The metabolism slows down during these periods. The

temperature can go down from a few tenth degrees. Time of the day: Body temperature is lowest in the early morning, when

metabolic rate and heat production are at their lowest. The body temperatureis highest in the afternoon and early evening when we are active. Body

temperatures normally change throughout the day, varying as much as 1.00C

between the early morning and the late afternoon. Exercise and physical labor: The role of muscles is predominant in the

production of heat; the muscular activities can increase the metabolism 4 to 5

times to the initial value of rest. Therefore, the temperature can rise from 0.2 to1. 50C according to the activity. However, hard work or strenuous exercise can

increase body temperature to as high as 38.3 to 400 C measured rectally. Stress: Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system can increase the

production of epinephrine and norepinephrine, thereby increasing metabolic

activity and heat production. The digestion: The combustion of the nutritious substances increases

the production of heat. The abundant meals increase the temperature by

the activation of the metabolism. On the other hand the fasting lowers the

temperature in the beginning, but if it is prolonged, it can increase it. Hot and

cold fluids can have mild effects on the oral temperature reading for 15 to 30

minutes after ingestion. The climate: The temperature of individuals living in tropical countries is of 1

degree more elevated than normal. Contrary in cold countries the temperature

is below the normal. If the patient has been outside in extremely cold weather

without suitable clothing, the body temperature may be low.

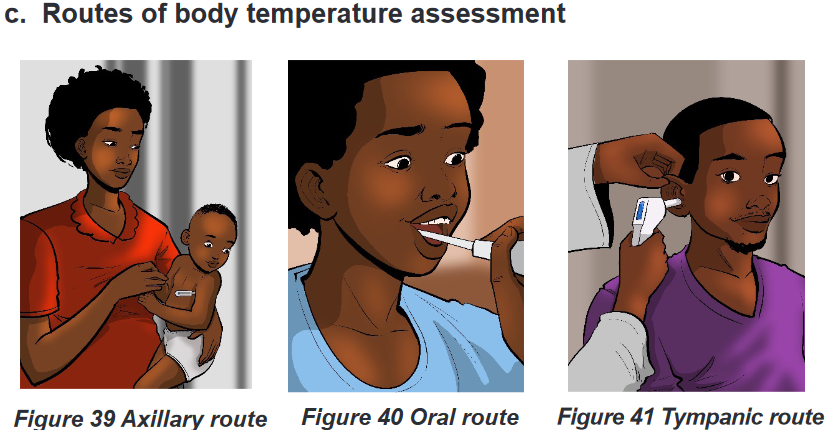

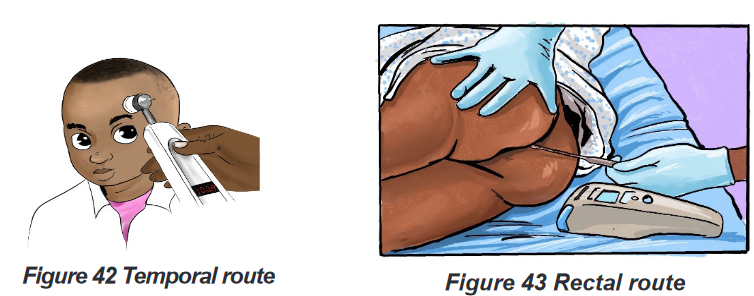

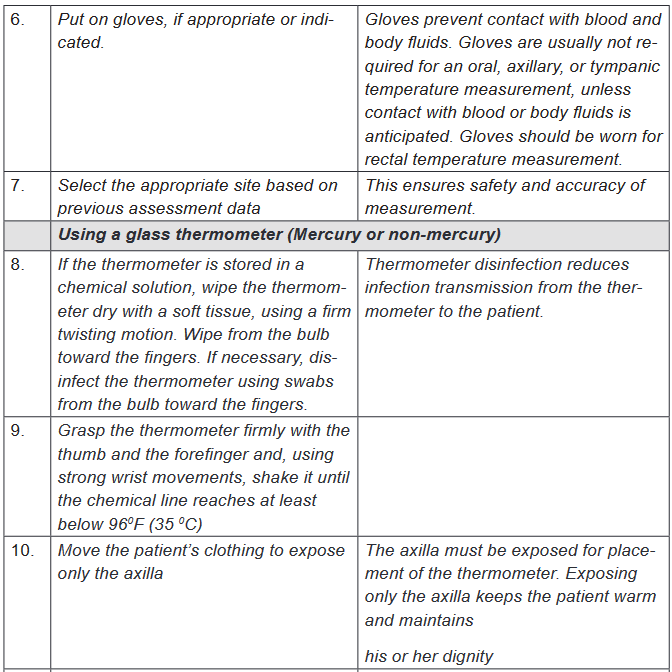

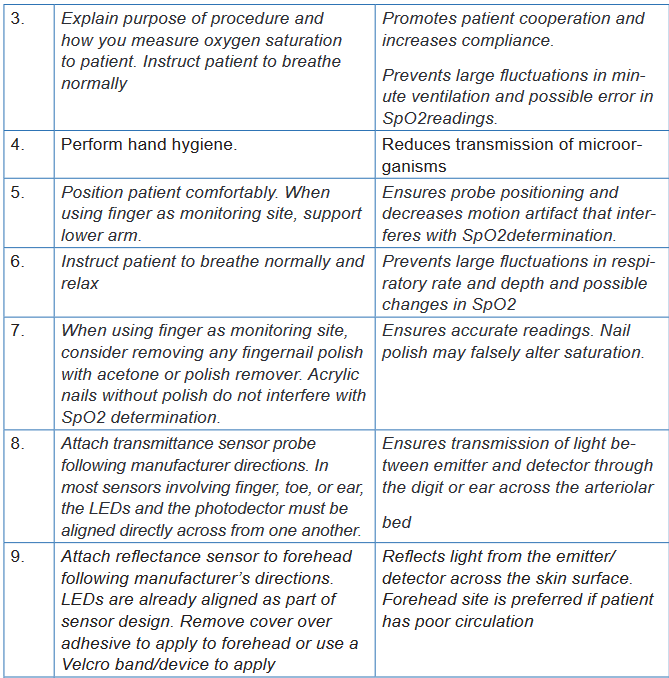

Body temperature is most accurate when measured at sites where there is a rich

blood supply. The common routes used to measure temperature are the axillary

(Figure 39 Axillary route) ,oral (Figure 40 Oral route), tympanic (Figure 41

Tympanic route), temporal artery(Figure 42 Temporal route), rectal (Figure 43

Rectal route) and skin routes. Rectal and tympanic membrane measurements

are used to represent core temperatures; oral and axillary measurements reflect

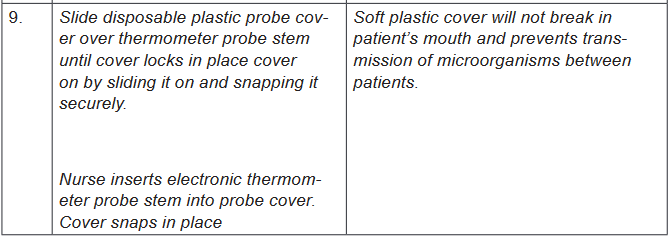

surface temperatures.Oral temperature is the most commonly used and probably the most convenient

method. Provided that it is done correctly, the oral temperature is a reasonably

accurate reflection of the body temperature. To accurately measure an oral

temperature, you must make certain the patient has not eaten, drunk, or smoked

within the last 15 to 30 minutes. After applying a disposable thermometer cover

sheath, the thermometer should be placed deep into the sublingual pocket under

the tongue.Rectal temperature readings are considered the most accurate, and they are the

true reflection of the core temperature of the body. However, rectal temperature is

contraindicated in many clinical situations; for example, people who are undergoing

rectal surgery, have diarrhea or diseases of the rectum, are immunosuppressed,

have a clotting disorder or have significant hemorrhoids. The rectal temperature is

approximately 1°F higher than the oral temperature.The axilla temperature is the preferred site for measuring temperature in newborns

because it is accessible and safe. It measures the surface temperature of the body,

and this method is not accurate if not correctly carried out. Properly carried out,

an axillary temperature is a reasonably accurate reflection of body temperature.

Axillary temperatures are lower than rectal temperatures. The axillary route is used

for patients who cannot hold the oral thermometer in place or for patients for whom

the oral route might pose a safety risk, such as a patient who is having seizures.The axillary route temperature is approximately1°F lower than the oral temperature.

The tympanic membrane is a frequent site for estimating core body temperature.

Like the sublingual oral site, the tympanic membrane has an abundant arterial

blood supply, primarily from branches of the external carotid artery.

Normal range of adult body temperature per site:

Orally 36,7oC to 37,2o C , average: 37oC

Axillary 35,6oC to 36,7o C, average: 36,5oC

Rectally 36,7oC to 37,8o C , average: 37,5oC

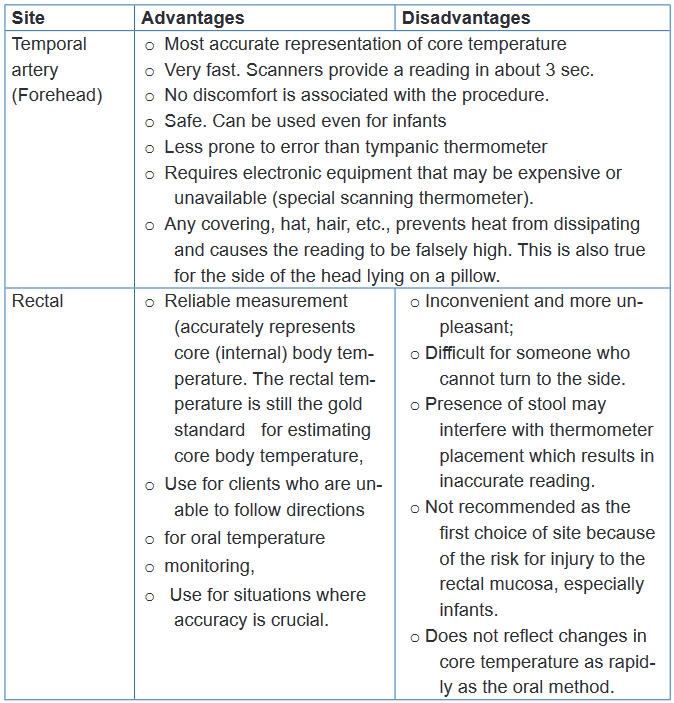

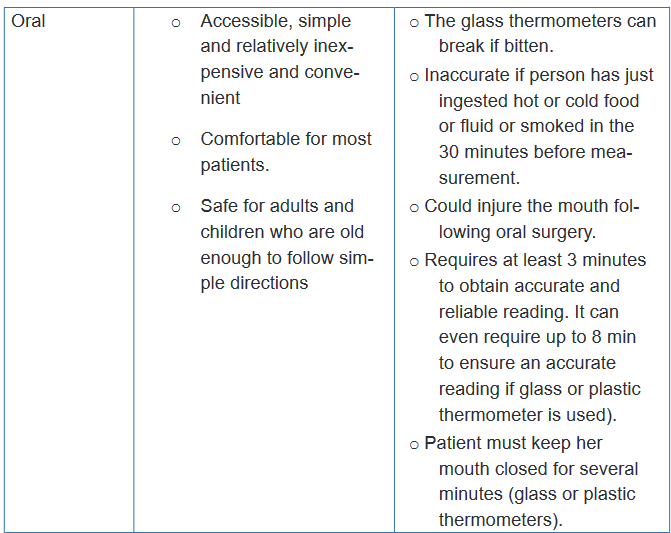

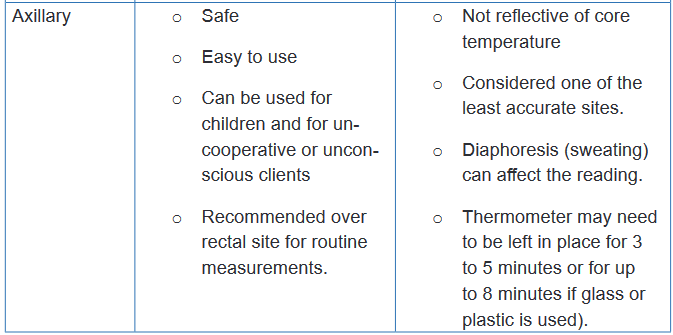

New born 36.1-37.7 (axillary)d. Advantages and disadvantages of sites for body temperature

measurement

e. Pathological variations (Alterations) of body temperature

There are two primary alterations in body temperature: pyrexia, hyperthermia or

fever and hypothermia. Pyrexia or fever is a body temperature above the normal

range. A very high fever that is above 40oC such as 41oC is called hyperpyrexia.

The client who has fever is referred to as febrile; the one who has not is afebrile.Very high temperatures, such as 41 to 420C, damage the cells throughout the body,

particularly in the brain where destruction of neuronal cells is irreversible. Damage

to the liver, kidneys and other body organs can also be great enough to disrupt

functioning and eventually cause death.Hypothermia which is a core temperature below 95°F (35°C), slows body

metabolism. Mild hypothermia is treated with warm clothes or blankets and ingestion

of warm drinks such as broth or soup. Because up to 40% of body heat can be lost

through the head, coverings such as a hat or scarf can dramatically help reduce

heat loss.Every patient with a fever will not present signs and symptoms of fever in the

same manner. Some of the common signs and symptoms that may indicatefever include: Flushed face , dry hot skin, dry mucous membranes, elevated pulse

rate and rapid respirations, droopy eyes, increased irritability or restlessness,

photophobia, which means the eyes have increased sensitivity to light, thirst,

headache, myalgia (muscle aches), lethargy or drowsiness, diaphoresis, anorexia

and nausea. A patient with hypothermia often presents the following signs and

symptoms: Decreased body temperature, pulse and respirations, severe shivering

initially and feeling of cold and chills, pale, cool, waxy skin, hypotension, lack of

muscle coordination, disorientation, drowsiness progressing to coma, decreased

urinary output.

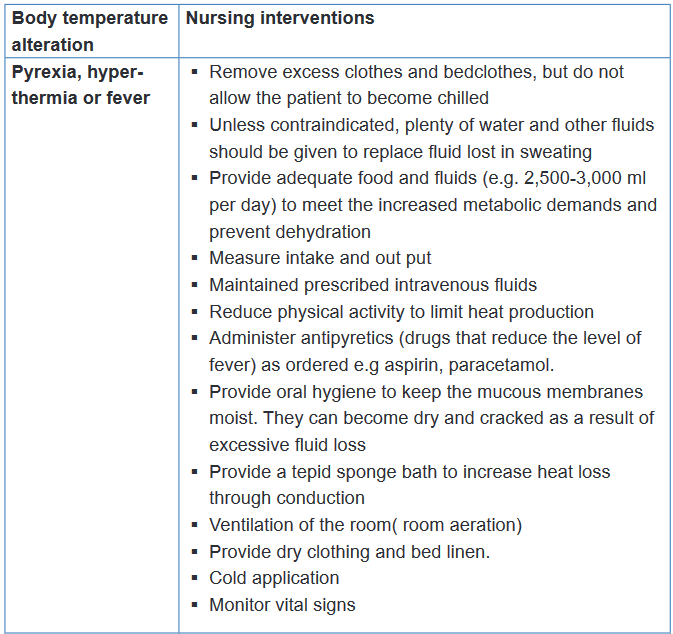

f. Nursing interventions for a patient with alterations of body

temperature

Self-assessment 3.2.1

1) What is the difference between core and surface temperature?

2) Among the following sites of body temperature assessment, which one is

the safest and most convenient site?

a) Oral

b) Tympanic

c) Axillary

d) Rectal

3) Mr. TA, 30 years old is hospitalized in a district hospital in room B

(Private room). During his assessment, the nurse notices that his body

temperature is 1030F.

a) How will the nurse interpret the body temperature of Mr. TA?

b) Based on the body temperature of Mr. TA, what will be the appropriate

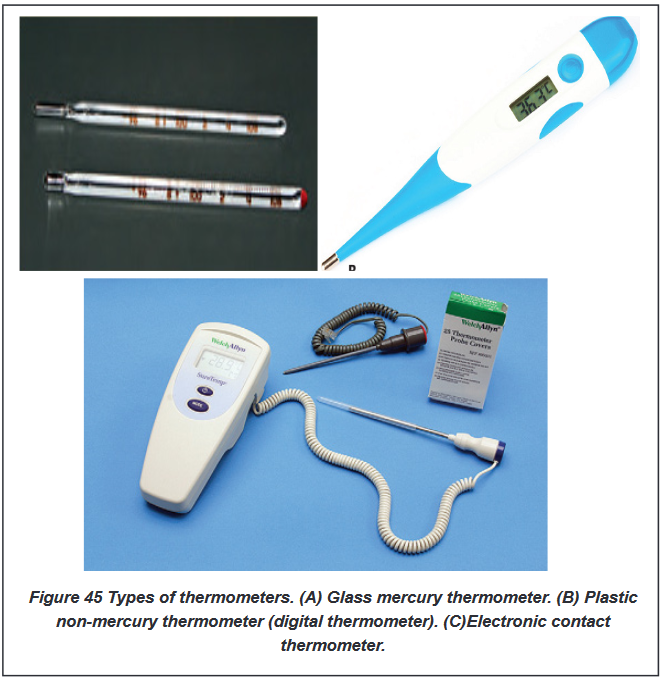

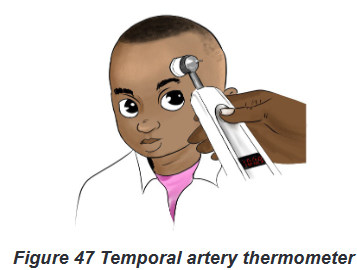

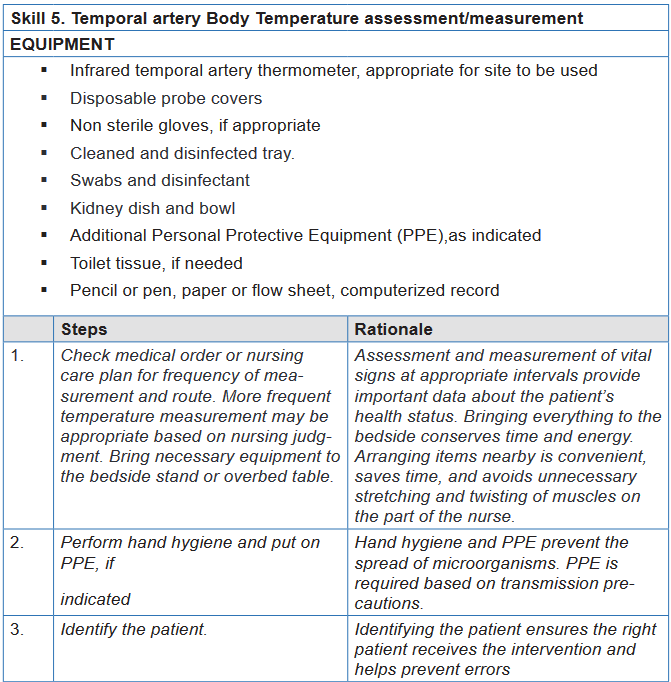

nursing interventions by the nurse?3.2.2 Body Temperature measurement/assessment

Learning activity 3.2.2.

In small groups of four (4) learners per each, read firstly the required equipment

and all the steps of axillary, oral, rectal, tympanic membrane and temporal artery

body temperature assessments in the provided procedural guides. Secondly,

use the provided materials for axillary, oral, rectal, tympanic membrane and

temporal artery body temperature assessments and measure the axillary, oral,

tympanic membrane and temporal artery body temperature of your partner.

N.B. In a group of four learners, two learners will pair and everyone will measure

the body temperature (axillary, oral, tympanic membrane and temporal artery)

of his/her partner, write down the results , interpret them and communicate the

results to his/her partner. For the measurement of rectal body temperature, you

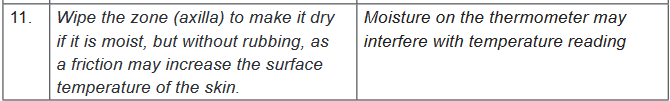

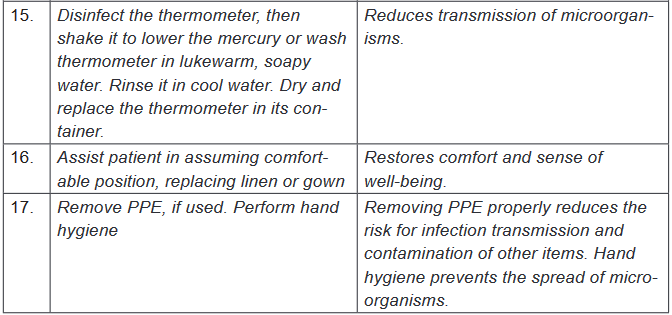

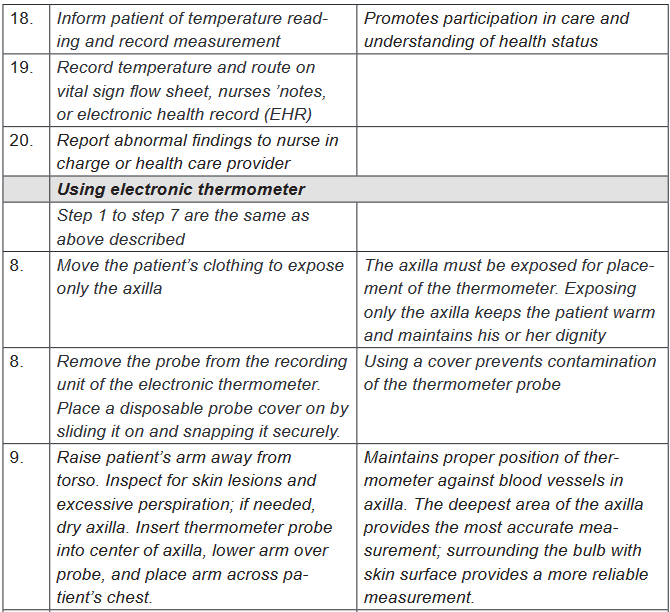

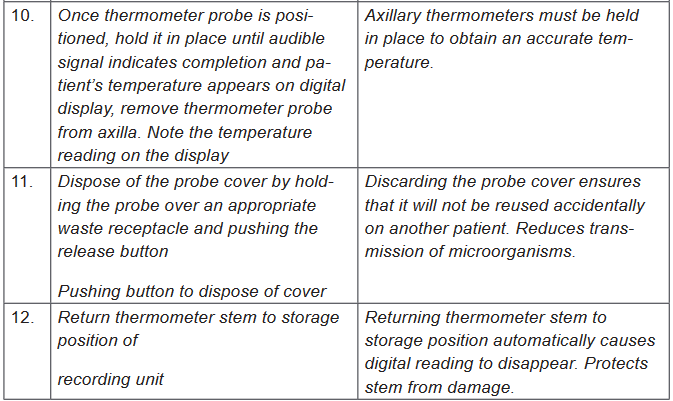

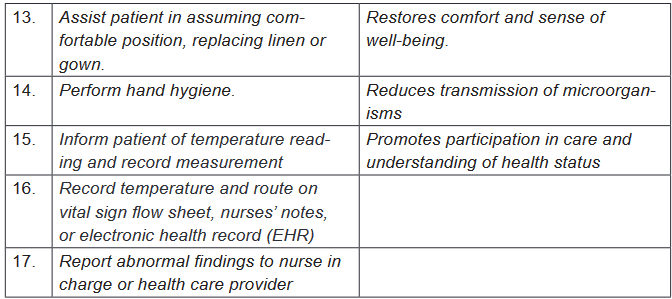

will measure it on the provided mannequins.a) Axillary body temperature assessment

To measure body temperature, several types of equipment and different procedures

might be used. To obtain an accurate measurement, choose an appropriate site,

the correct equipment, and the appropriate tool based on the patient’s condition. If

a temperature reading is obtained, it is better to document also the site used along

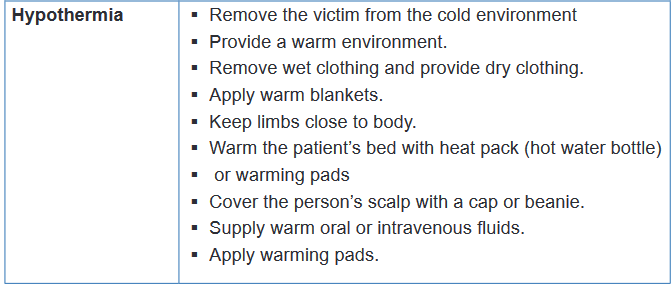

with the measurement.Various types of clinical thermometers may be used to assess the axillary body

temperature, including mercury glass thermometer, a plastic non-mercury

thermometer, electronic contact thermometer. Plastic non-mercury thermometers

have a digital readout, with oral, axillary, and rectal settings, requiring you to preset

the correct route before taking the temperature. Electronic contact thermometers

consists of a rechargeable battery-powered display unit, a thin wire cord, and

a temperature-processing probe covered by a disposable probe cover. This

thermometer can provide a reading in 2 to 60 seconds, depending on the model

and may be used to assess oral, axillary, or rectal temperatures. The mercury-

in-glass thermometer has been eliminated from health care facilities (no longer

advised) because of the environmental hazards of mercury.

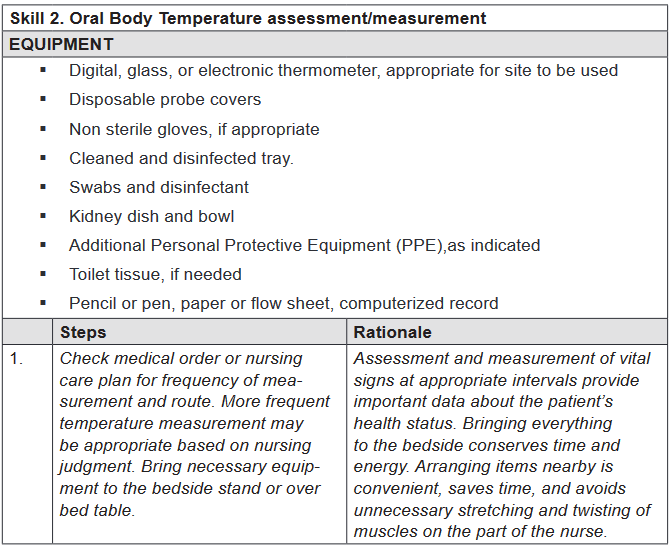

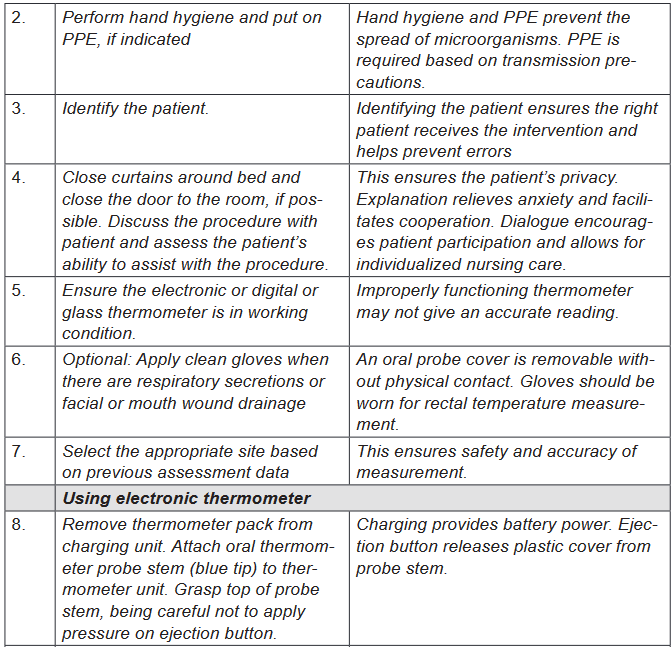

b) Oral body temperature assessment

Various types of clinical thermometers may be used to assess the oral body

temperature, including mercury glass thermometer (no longer advised), a plastic

non mercury thermometer (digital) and electronic contact thermometer.

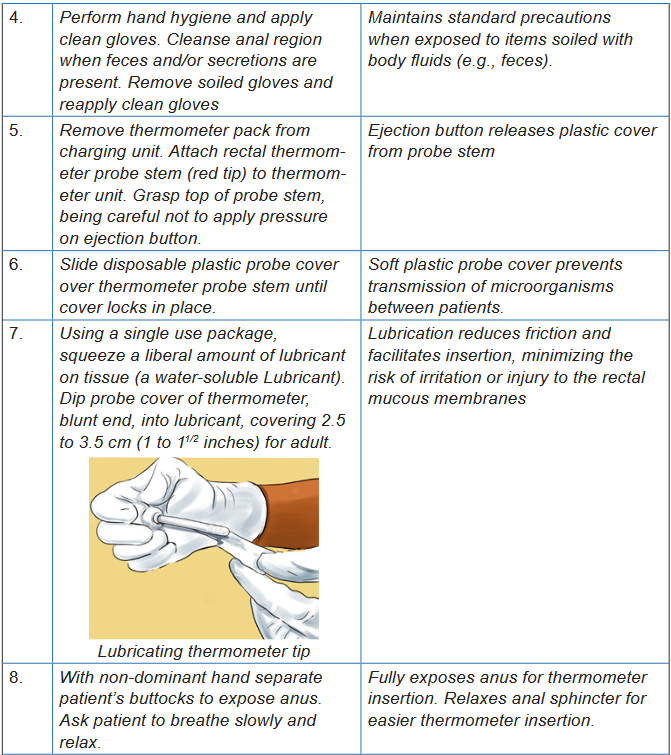

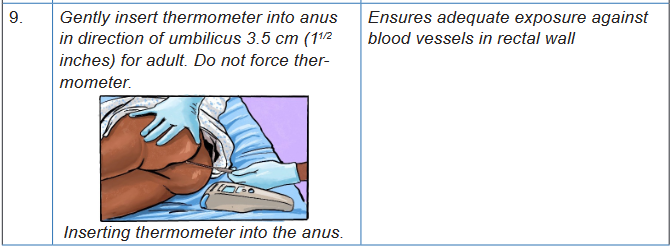

c) Rectal body temperature assessment

Various types of clinical thermometers may be used to assess the oral body

temperature, including mercury glass thermometer (no longer advised), a plastic

non-mercury thermometer (digital) and electronic contact thermometer.

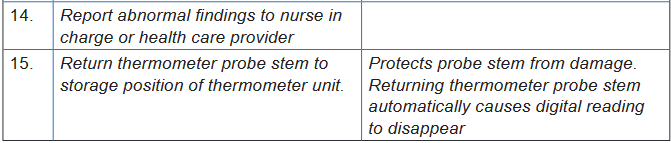

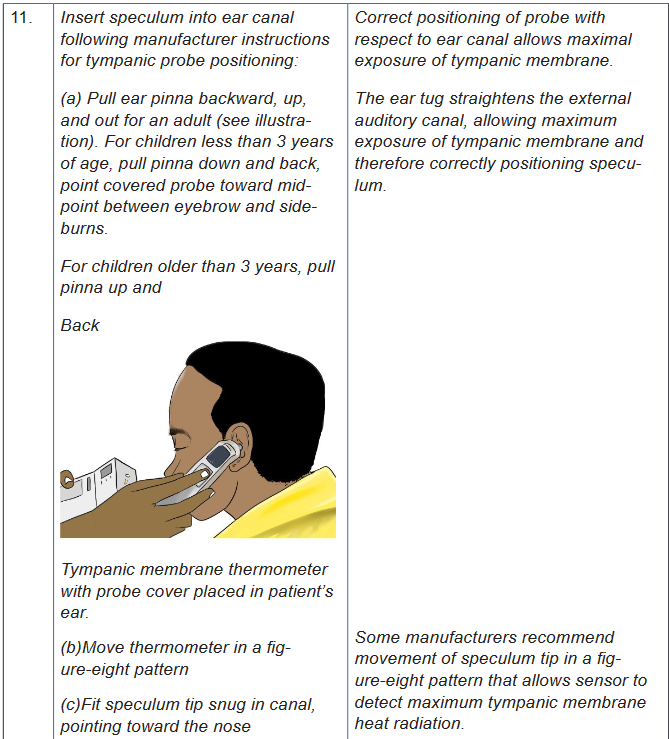

d) Tympanic membrane body temperature assessment

Infrared (tympanic) thermometer is used,. Infrared (tympanic) thermometers

(another form of electronic thermometer); is an otoscope-like speculum with an

infrared sensor tip which detects heat radiated from the tympanic membrane.

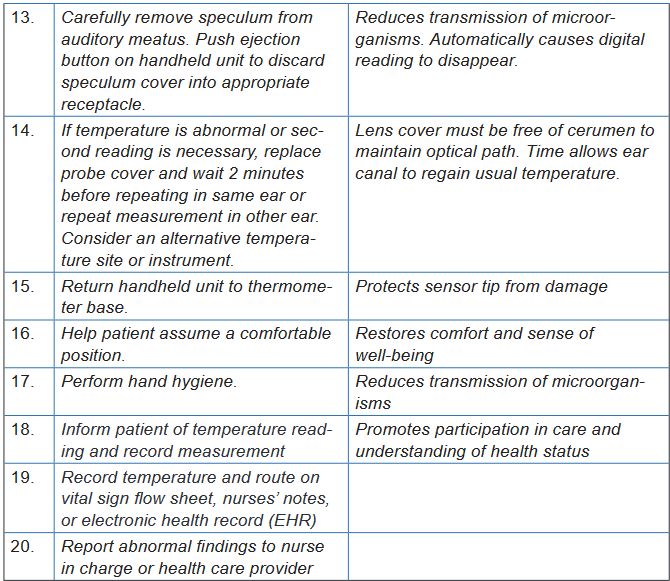

e) Temporal artery body temperature assessment

For a temporal artery thermometer (another form of electronic thermometer); a

handheld scanner with an infrared sensor tip detects the temperature of cutaneous

blood flow by sweeping the sensor across the forehead and just behind the ear.

Self -assessment 3.2.2

Instructions:

For you to master the technique of temporal artery body temperature

measurement; go back to your previous groups of four ; let each learner

measures one more time the temporal artery body temperature. The teacher

will be facilitating and observing each student while carrying out the procedure.

After measuring temporal artery body temperature, do the following:

a) Record the temperature reading

b) Interpret the temperature reading.

c) Communicate the result to your partner.3.3. Pulsation/Pulse measurement

Learning activity 3.3.

For Overview

Use the provided book of Fundamentals of Nursing to read the materials on

Pulse under the vital signs unit and make a summary note of the following:

1) Definition of Pulse

2) Normal values and abnormal values of pulse

3) Factors affecting Pulse

4) Sites of pulse palpation

5) Different methods of Pulse taking or How to assess the pulse rate

6) Basic nursing interventions during abnormal pulse.For procedure

Using checklist provided and equipment for pulse taking (see checklist); read all

steps of pulse rate taking in order for you to measure correctly the pulse for your

partner.

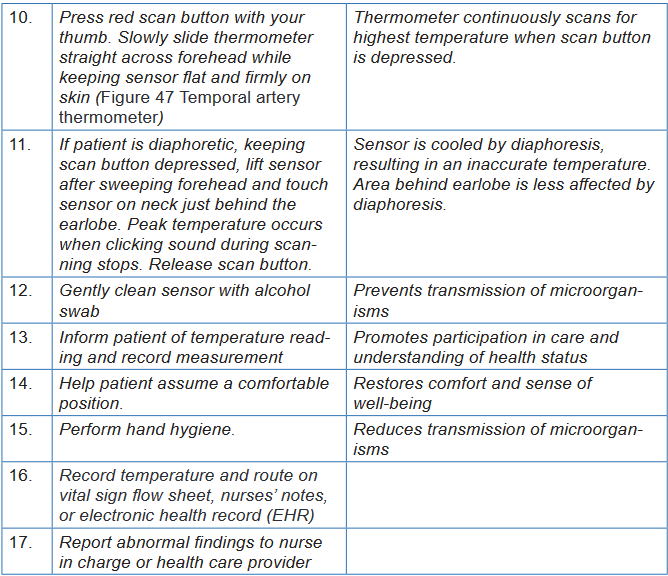

1) Observe the images of pulse taking for your guidance. (Figure 48 to

Figure 55)

2) Form pairs of 2 students and each one of you measure a peripheral pulse

selecting the site of Radial artery used for routine assessment of vital

signs

3) Assess the pulse at the apex of the heart (apical pulse) or at a place

where an artery can be pressed by the fingers against a bone (peripheral

pulses).

4) Use Different methods of how to assess the pulse rate:

5) Write down the results for your partner; Interpret results of pulse showing

normal and abnormal values.3.3.1. Pulse overview

The pulse corresponds to the contractions or beats of the heart and is counted by

the number of beats per minute (bpm). The pulse is the rhythmic expansion of an

artery produced when a bolus of oxygenated blood is forced into it by contraction of

the heart. The pulse is the palpable bounding of blood flow noted at various points

on the body and is an indicator of circulatory status.

a) Normal and abnormal values of Pulse

i. Normal Pulse Rate

The normal range for healthy young and middle-aged adults is 60 to 100 beats/

min (bpm), with an average rate of 70 to 80 beats/min. The normal range of

pulse rate for adults is 60 to 100 bpm and is measured in beats per minute. Taking

the pulse is a quick and simple way to assess the condition of the heart, blood

vessels, and circulation. While assessing pulse rate as a nurse, you will assess

three characteristics of the pulse: Rate, Rhythm and Volume (strength).ii. Abnormal values of Pulse

A pulse less than 60 bpm is known as bradycardia; a pulse greater than 100

bpm is termed tachycardia.b) Pathological variations of Pulse

There are three abnormalities of Pulse: Tachycardia, Bradycardia and

DysrhythmiaThe first two abnormalities (Tachycardia, Bradycardia) are related to the pulse rate

and the third one (Dysrhythmia) is related to pulse rhythm.Tachycardia is an abnormally elevated HR (Heart Rate), above 100 beats/min in

adults. Bradycardia is a slow rate, below 60 beats/min in adults. In other words, a

pulse less than 60 bpm is known as bradycardia (brady = slow, cardia = heart); a

pulse greater than 100 bpm is termed tachycardia (tachy = rapid, cardia = heart).Dysrhythmia: is an abnormal rhythm when the intervals between beats vary

enough to be noticeable, and is called dysrhythmia.There are also abnormal rhythms which are a group of irregular beats that form a

pattern. An irregular heart rhythm can be very serious and may require additional

assessment by electrocardiogram (ECG), a procedure that traces the electrical

pattern of the heart.c) Factors Affecting Pulse Rate

Because the heart and blood vessels are regulated by the nervous system, conditions

that interfere with normal functioning of the nervous system also affect the pulse.Other factors that may cause variations in pulse rate, rhythm, or quality

include the following: Developmental level (Age): New-borns have a rapid pulse rate. The rate

stabilizes in childhood and gradually slows through old age:

o New-borns: 120–160 bpm

o 1–2 years: 90–120 bpm

o 3–18 years: 80–100 bpm

o Adults: 60–100 bpm

Gender: Adult women have a slightly more rapid pulse rate than do adult men.

Exercise, Meditation, rest, sleep: Muscle activity or exercise normally

increases the pulse rate but meditation, rest and sleep lower the pulse rate.

Food: Ingestion of food causes a slight increase in pulse rate for several

hours.

Stress, Emotions and hormones: Stimulate sympathetic nervous system,

increasing pulse rate.

Fever or Body temperature: The pulse rate tends to increase about 10

beats/ min for each degree Fahrenheit of temperature elevation. As body

temperature increases, each degree Fahrenheit results in speeding the

heart approximately 10 bpm. As the body cools, each degree results in

slowing the pulse by 10 bpm

Disease: Diseases, such as heart disease, hyperthyroidism, respiratory

diseases, and infections, are generally associated with increased pulse

rates. Hypothyroidism is associated with decreased pulse rates.

Blood loss: Small blood loss is generally well tolerated and produces only

a temporary increase in pulse rate but a large blood loss brings about an

increase in pulse rate to compensate for the decreased blood volume. Position changes: Standing and sitting positions generally cause a temporary

increase in pulse rate and decrease in blood pressure as a result of blood

pooling in the veins of the feet and legs. This decreases blood return to the

heart, decreasing blood pressure and subsequently increasing heart rate Medications: Stimulant drugs (e.g., epinephrine) increase pulse rate.

Cardiotonics (e.g., digitalis) and opioids (e.g., narcotic analgesics) or

sedative drugs decrease pulse rate. Hypoxia: Increases the pulse rate.

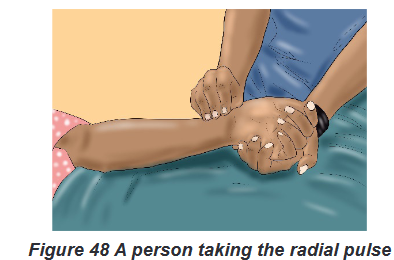

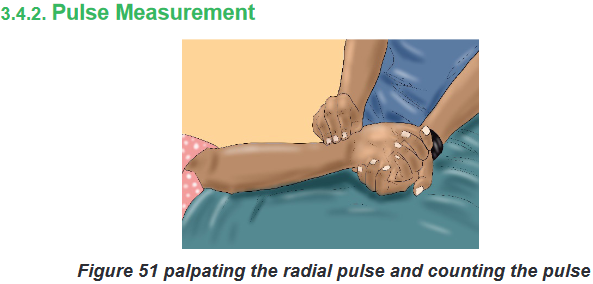

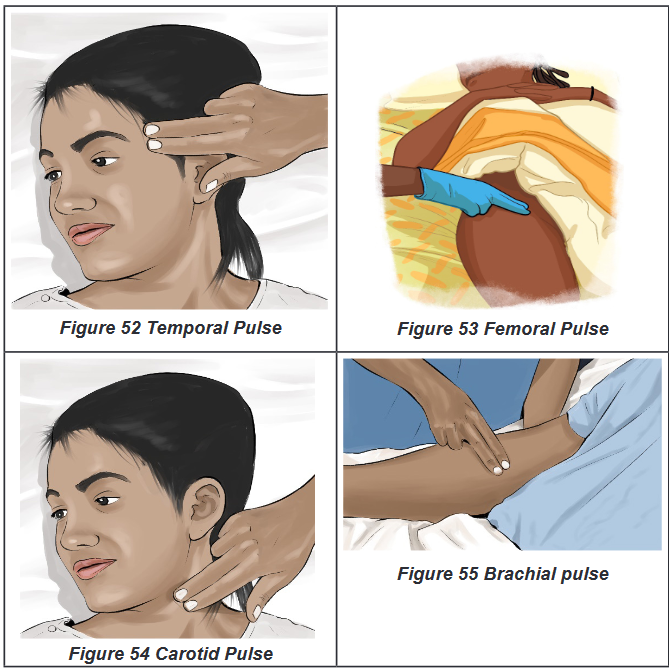

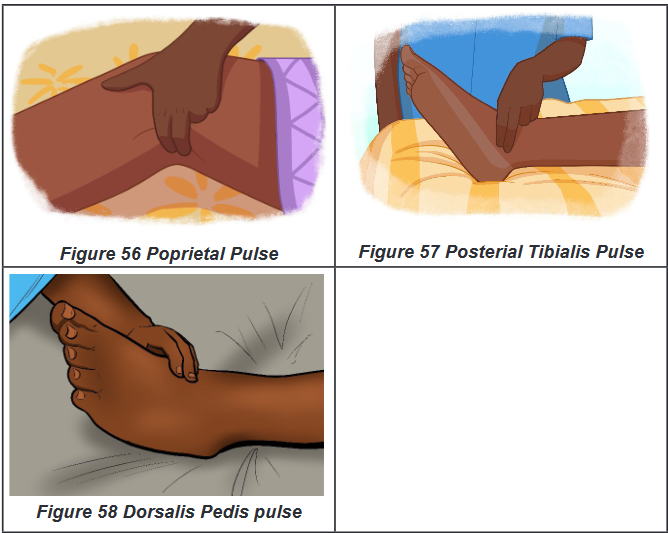

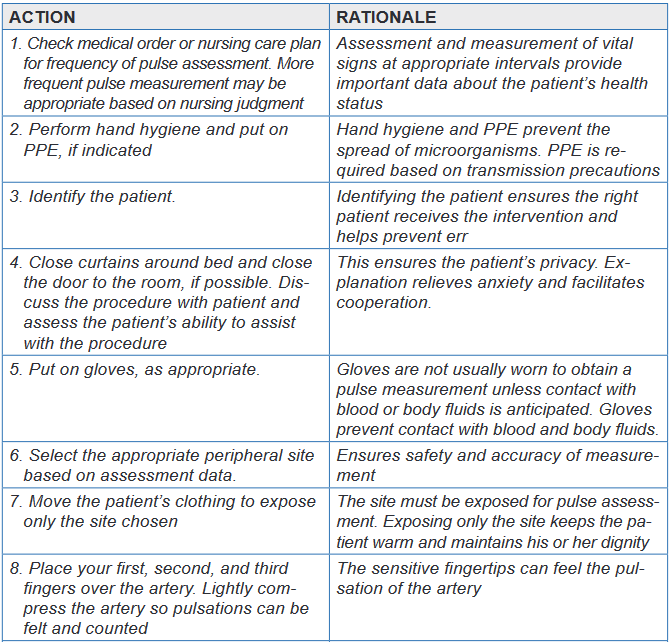

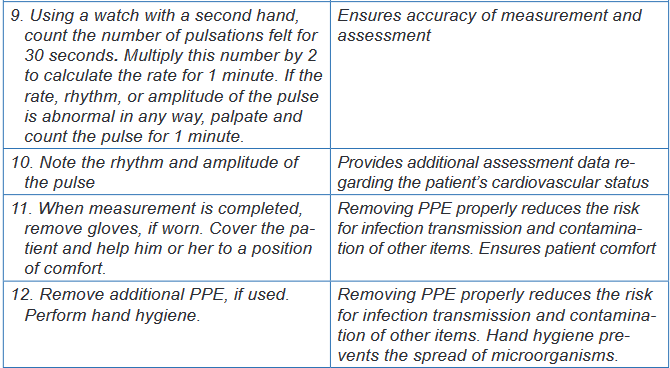

d) Sites of Pulse palpation

i. Peripheral Pulse Sites:

There are various other pulse sites where the pulse may be palpated by applying

gentle fingertip pressure over the artery against the underlying bone. These sites

are known as the peripheral pulses.

The peripheral pulse sites include the following: Temporal: can be used when

radial pulse is not accessible; Carotid: used in cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary

resuscitation (CPR); Brachial: used to measure BP; can be used to assess pulse

rate in small children; Radial: routinely used for pulse rate assessment; Femoral:

used to determine circulation to the leg, cardiac arrest; Popliteal: used to determine

circulation to the lower leg; Posterior tibialis: used to determine circulation to the

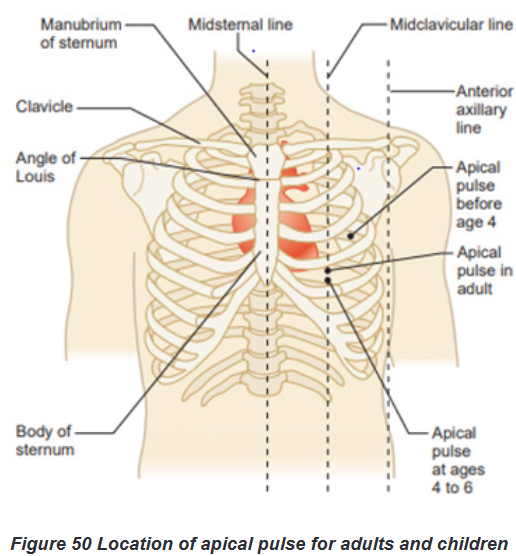

foot and Dorsalis pedis: used to determine circulation to the foot.ii. Apical Pulse Site:

For Apical pulse; Nurses assess the pulse at the apex of the heart. Auscultate

(listen to) an apical pulse over the apex of the heart, as the heart beats.

Indications of apical pulse

When cardiac output declines significantly, peripheral pulses weaken and

are difficult to palpate. The radial and apical locations are the most common

sites for pulse rate assessment If the radial pulse is abnormal or intermittent resulting from dysrhythmias or

if it is inaccessible because of a dressing or cast, assess the apical pulse. When a patient takes medication that affects the HR, the apical pulse

provides a more accurate assessment of heart function. The brachial or apical pulse is the best site for assessing an infant’s or

young child’s pulse because other peripheral pulses are deep and difficult

to palpate accurately.a. Nursing interventions during abnormal Pulse

Specific nursing activities and focused assessments for a patient with a dysrhythmia

depend on the cause of the problem and on specific orders from the physician. For

example, a client with a pulse rate of 50 beats/min is usually considered to have

bradycardia. However, such a slow resting heart rate would be perfectly normal for

a well-trained athlete.Some dysrhythmias are benign; that is, they are not dangerous to the client, and

they require no interventions. Nursing strategies that address dysrhythmias,

regardless of cause, include the following: Closely monitor the patient’s VS (Vital Sign): A reduced heart rate

may alter blood pressure and tissue perfusion. The extent of intervention

depends on the effect of the dysrhythmia on the client’s other vital signs. Monitor the patient’s activity tolerance: The degree of activity, orientation,

and level of fatigue while the dysrhythmia is present are indicators of the

patient’s ability to tolerate the dysrhythmia. Collect and assess laboratory data as prescribed: Cardiac function

depends on normal electrolyte balance, particularly potassium, calcium,

and magnesium levels. If a client is receiving medications that affect cardiac

rhythm, serum levels of these medications must be checked periodically. Help determine the cause of the dysrhythmia: Determine when the client

experiences the dysrhythmia. Are there precipitating or alleviating factors? Administer antidysrhythmic medications: These are prescribed to

control the heart rhythm Provide emotional support: The client experiencing a dysrhythmia may be

frightened by the experience. Explain all procedures to the client and family

members, and maintain a calm presence.

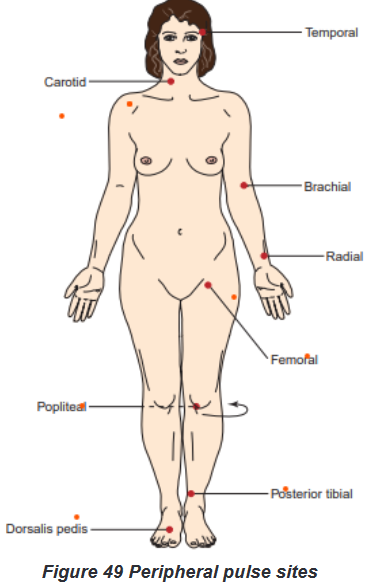

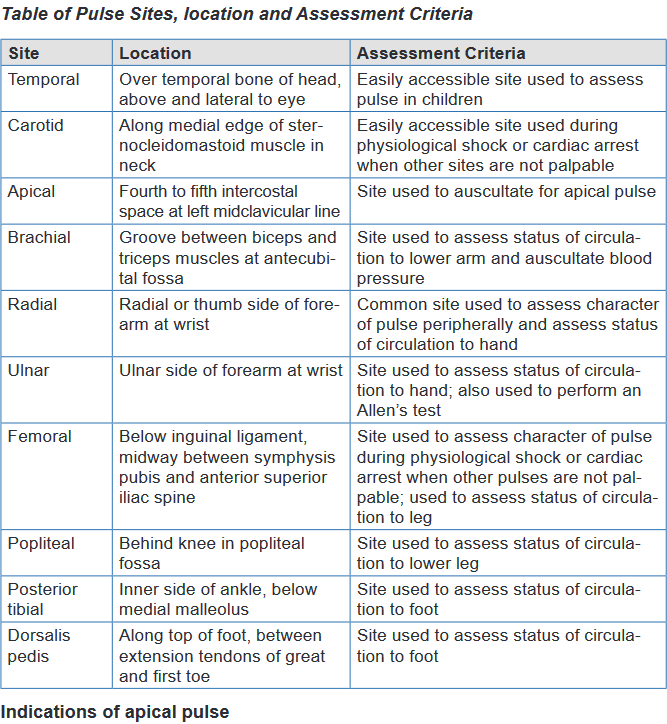

a) Assessment of pulse

To assess the pulse rate, count the number of beats per minute while palpating or

auscultating. Begin the count with one, rather than zero. For normal, healthy adults,

you can determine the rate of a regular heart rhythm by counting the pulse for 15

seconds and multiplying the result by 4. Research is conflicting, but some studies

indicate that a 30-second count is more accurate. If the pulse is irregular or slow,

always count for 1 full minute.i. Assessing Peripheral Pulses

Make sure the client is resting while you assess the pulse.

Count for 15 or 30 seconds if the pulse is regular; count for 60 seconds if it

is irregular.

Note pulse rate, rhythm, and quality.

Compare pulses bilaterally.ii. Assessing the Apical Pulse;

Assessing the apical rate requires a stethoscope and is done as follow:

Position the patient supine or sitting.

Palpate and place the stethoscope at the 5th intercostal space at the

midclavicular line.

Count for 60 seconds.

Note pulse rate, rhythm, and quality and the S1 and S2 heart sounds.Assessing for an Apical-Radial Pulse Deficit

Palpate and place stethoscope over apex of the heart.

Palpate the radial pulse.

Have two nurses carry out the procedure, if possible.

Count for 60 seconds, simultaneously.

Compare the pulse rate at both sites; calculate the difference.Pulse Amplitude

Pulse amplitude typically is graded as 0 to 4:

0 (absent pulse): pulse cannot be felt, even with the application of extreme

pressure

1 (thread pulse): pulse is very difficult to feel, and applying slight pressure

causes pulse to disappear • 2 (weak pulse): pulse is stronger than a thready

pulse, but applying light pressure causes pulse to disappear

3 (normal pulse): pulse is easily felt and requires moderate pressure to

make it disappear

4 (bounding pulse): pulse is strong and does not disappear with moderate

pressureImplementation using the procedural guide for peripheral pulse measurement

Equipment

Watch with second hand or digital readout

Pencil or pen, paper or flow sheet, computerized record

Nonsterile gloves, if appropriate; additional PPE, as indicated

Evaluation

The expected outcomes are met when the patient’s pulse is assessed accurately

without injury and the patient experiences minimal discomfort.Unexpected situations and associated interventions

The pulse is irregular: Monitor the pulse for a full minute. If the pulse is

difficult to assess, validate pulse measurement by taking the apical pulse for

1 minute. If this is a change for the patient, notify the physician. The pulse is palpated easily, but then disappears: Apply only moderate

pressure to the pulse. Applying too much pressure may obliterate the pulse. In case you cannot palpate a pulse: Use a portable ultrasound Doppler

to assess the pulse. If this is a change in assessment or if you cannot find

the pulse using an ultrasound Doppler, notify the physician. If you can find

the pulse using an ultrasound Doppler, place a small X over the spot where

the pulse is located. This can make palpating the pulse easier because the

exact location of the pulse is known.Special considerations

General Considerations

The normal heart rate varies by age.

When palpating a carotid pulse, lightly press only one side of the neck at

a time. Never attempt to palpate both carotid arteries at the same time.

Bilateral palpation could result in reduced cerebral blood flow

If a peripheral pulse is difficult to assess accurately because it is irregular,

feeble, or extremely rapid, assess the apical rate.Infant and Child Considerations

For children younger than 2 years of age, assess the apical pulse.

Do not measure the radial pulse because it is difficult to palpate accurately

in this age group

Measure the apical rate if the child has a cardiac problem or congenital

heart defect.Self-assessment 3.4.

For overview

1) What are the normal values of pulse?

2) Explain the three abnormalities or variations of Pulse?

3) List the Eight peripheral pulse sites

4) Explain how to assess peripheral, and apical pulses?

5) Describe the seven Nursing strategies that address dysrhythmias,

regardless of causeFor procedure

For you to master the technique of Pulse rate taking; going back to your previous

groups of two; let each student takes one more time the pulse of his /her partner.

The teacher will be facilitating and observing each student while carrying out

the procedure.

1) Record the results

2) Interpret them.

3) Communicate results to your partner.3.4. Blood Pressure

Learning activity 3.4.

Section (a): For over view

Use the provided book of Fundamentals of Nursing and read the materials

on blood pressure under the vital signs unit and make a summary note of the

following:

1) Definition of blood pressure

2) Difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure

3) Determinants of blood pressure

4) Normal values of blood pressure

5) Factors affecting blood pressure

6) Alterations of blood pressure

7) Nursing interventions for a patient with alterations of blood pressureSection (b): For measurement

In small groups of four (4) learners per each, read firstly the required equipment

and all the steps of blood pressure assessment in the provided procedural

guide. Secondly, use the provided materials for blood pressure measurement

and measure the blood pressure of your partner. N.B. In a group of four

learners, two learners will pair and every one will measure the blood pressure

of his/her partner, write down the results and interpret them.3.4.1. Blood Pressure overview

Blood pressure is the force exerted on the walls of an artery created by blood

as it flows through the arteries.Blood flows throughout the circulatory system because of pressure changes,

moving from an area of high pressure to an area of low pressure. Under high

pressure the left ventricle contracts and ejects blood into the aorta which creates

the peak pressure known as systolic pressure. When the ventricles relax, the

blood remaining in the arteries exerts a minimum pressure know as diastolic

pressure. Thus, Diastolic pressure is the minimal pressure exerted against the

arterial wall at all times. In other words, systolic blood pressure is the pressure

exerted by the blood flow on the arterial wall at the time of the systole: that means

that when the left ventricle of the heart contracts throws blood in the circulation, the

arteries are then to their maximum of tension. And diastolic blood pressure is the

pressure exerted by blood on the arteries during the diastole. That means that at

the time of the laxity of the ventricle (at rest).Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and recorded as a

fraction: systolic pressure over the diastolic pressure. According to the National

Heart Foundation of Australia (2013), normal blood pressure for a healthy adult

is usually less than 120/80 mm Hg (i.e. systolic blood pressure less than 120 and

diastolic blood pressure less than 80 mm Hg). The difference between the diastolic

and the systolic pressures is called the pulse pressure. A normal pulse pressure

is about 40 mm Hg but can be as high as 100 mm Hg during exercise. A consistently

elevated pulse pressure occurs in arteriosclerosis. A low pulse pressure (e.g. less

than 25 mm Hg) occurs in conditions such as severe heart failure.a) Normal values of blood pressure

The systolic pressure varies between 90 and 140 mm Hg (adult), for men

aged of 45 years and more, it can go up to 150mmHg.

The diastolic pressure, it is between 60 and 90 mm Hg (adult)

The pulse pressure can vary from 30 to 50 mm Hg

Newborn: 65-90/ 30-60 mmHg (systolic/ diastolic)

Infants: 65-125/ 40-90 mmHg (systolic/ diastolic)

Children: 80-120/ 45-85 mmHg (systolic/ diastolic)

Adolescents: 95-135/50-70 mmHg (systolic/ diastolic)b) Determinants of blood pressure

Arterial blood pressure is the result of several factors: the pumping action of the heart,

the peripheral vascular resistance (the resistance supplied by the blood vessels through

which the blood flows), the blood volume, blood viscosity and elasticity of vessels. The pumping action of the heart: Cardiac output is the volume of blood

pumped into the arteries by the heart during 1 minute. When the pumping

action of the heart is weak, less blood is pumped into arteries, and the blood

pressure decreases. When the heart’s pumping action is strong and the volume

of blood pumped into the circulation increases, the blood pressure increase.

The cardiac output for an adult at rest is 4 to 6 liters of blood each minute. The peripheral vascular resistance: if the caliber (lumen) of the peripheral

vessels is abnormally small, the blood pressure increases, inversely if the

caliber is very large the blood pressure decreases. The blood volume: The volume of blood circulating within the vascular system

affects BP. Most adults have a circulating blood volume of 5000 ml. Normally

the blood volume remains constant, when it decreases, for example in case of

hemorrhage, the blood pressure is low. If it increases (blood transfusions), the

blood pressure rises. The blood viscosity or consistence of the blood: more blood is viscous

(thick); more the blood pressure will be raised. Because the resistance is

increased. The hematocrit, or percentage of red blood cells in the blood,

determines blood viscosity. When the hematocrit rises and blood flows slowly,

arterial blood pressure increases. The heart contracts forcefully to move the

viscous blood through the circulatory system. The elasticity of vessels: the vessels with a reduced elasticity, offer more

resistance to the blood passage. Therefore, if the resistance increases, the

blood pressure will be increasedc) Factors affecting blood pressure

Among the factors influencing blood pressure are age, exercise, stress, ethnicity,

obesity, gender, medications, obesity, diurnal variations, medical conditions and

body temperature. Age: The blood pressure varies with the age. It is usual to note a progressive

increase of blood pressure with the age. In elderly people, elasticity of the

arteries is decreased. The arteries are more rigid and less yielding to the

pressure of the blood. This produces an elevated blood pressure for the

elderly. Exercise: Physical activity increases both the cardiac output and hence

the blood pressure, thus a rest of 20 to 30 minutes following exercise is

indicated before the blood pressure can be reliably assessed. Stress: Anxiety, fear, pain, and emotional stress result in sympathetic

stimulation. Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system increases

cardiac output and vasoconstriction of the arterioles, thus increasing the

blood pressure. Anxiety raises BP as much as 30 mmHg. Sex/ Gender: After puberty, females usually have lower blood pressures

than males of the same age, this difference is thought to be due to hormonal

variations. After menopause, women generally have higher blood pressures

than before. For men, the maxima are from 125 to 140 mm Hg whereas for

women of the same age it is less elevated at 115 to 130. For the minima, it

is generally the same for two sexes. Diurnal variations: Pressure is usually lowest early in the morning, when

the metabolic rate is lowest, then rises throughout the day and peaks in the

late afternoon or early evening. Disease process: any condition affecting the cardiac output, blood viscosity,

and/ or compliance of the arteries, has a direct effect on the blood pressure. Position: A person in lying down position normally the blood pressure is

low, while in standing or seated position the blood pressure is high. Medications: many medications may increase or decrease the blood

pressure. Obesity: pressure is generally high in some overweight and obese people

than in people of normal weight.d) Pathological variations or alterations of blood pressure

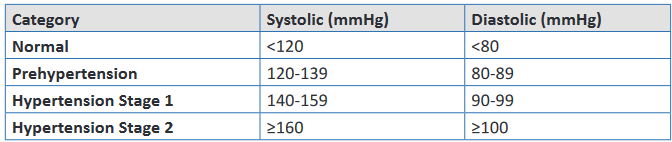

The two common alterations of blood pressure are hypertension and hypotension.i. Hypertension

Hypertension is a blood pressure that is persistently above normal. In other words,

hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) greater than 140mmHg

and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) greater than 90mmHg. Hypertension is often

asymptomatic disorder characterized by persistently elevated blood pressure.

Factors such as obesity, cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol intake, elevated

blood cholesterol, lack of physical exercises and continued exposure to stress are

risk factors for hypertension.Hypertension cannot be diagnosed/confirmed unless an elevated blood pressure

is found when properly measured twice with well-maintained equipment at different

times, it is usually asymptomatic and is often a contributing factor to myocardial

infarctions and stroke. An elevated blood pressure of unknown cause is called

primary hypertension. An elevated blood pressure of known cause is called

secondary hypertension.

Classification of Blood Pressure for Adults ages (18yearsand older)

Nursing interventions for a patient with hypertension:

Put the patient in supine position

Assure calmness around him and to reassure maximum relaxation.

Give glucose solution drip

Give diuretic if the high blood pressure is very important

Continue observation

Treat cause

Refer to the hospital center if you are in health center or seek for medical

advice.ii. Hypotension

Hypotension is a blood pressure that is below normal. It is an SBP less than

90mmHg.For most individuals hypotension is an abnormal finding associated with an

illness (e.g., hemorrhage or myocardial infarction). Hypotension occurs when

arteries dilate, the peripheral vascular resistance decreases, the circulating

blood volume decreases, or the heart fails to provide adequate cardiac

output. Signs and symptoms associated with hypotension include pallor, s k i n

mottling, clamminess, confusion, dizziness, chest pain, increased heart

rate, and decreased urine output. Hypotension is usually life threatening and

needs to be reported immediately to the patient’s health care provider.Nursing interventions for a patient with hypotension

Put the patient in Trendelenburg

Give physiological solution drip of preference or Ringer Lactate

Continue observation

Treat cause

Refer to the hospital if you are in health center or alert the physician when

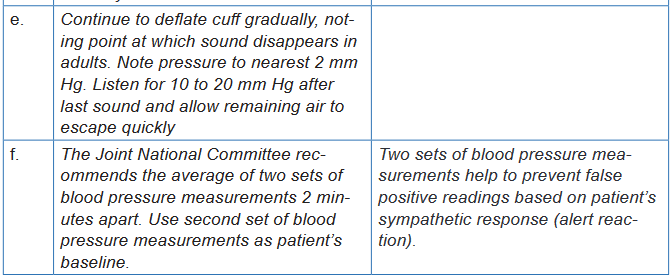

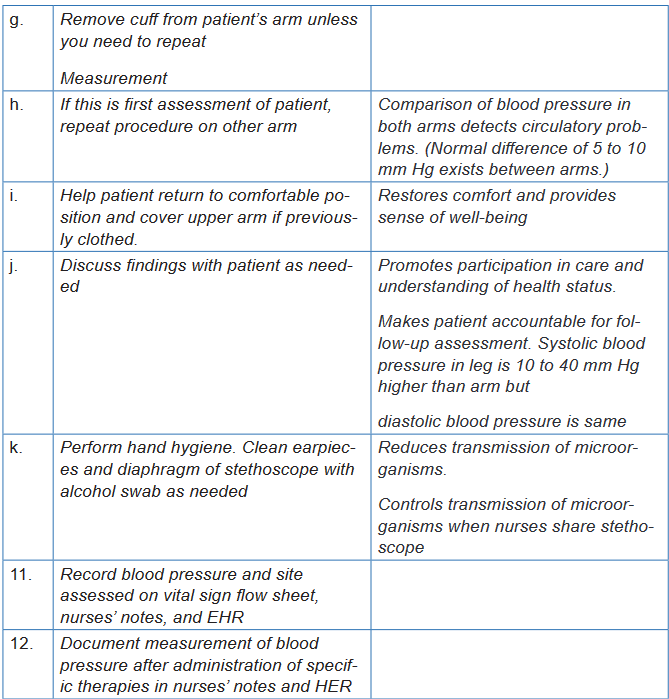

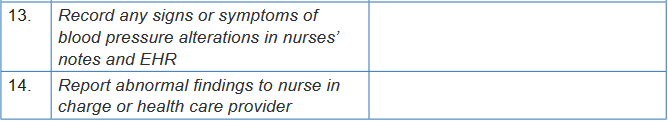

you are at the hospital3.4.2. Blood Pressure measurement

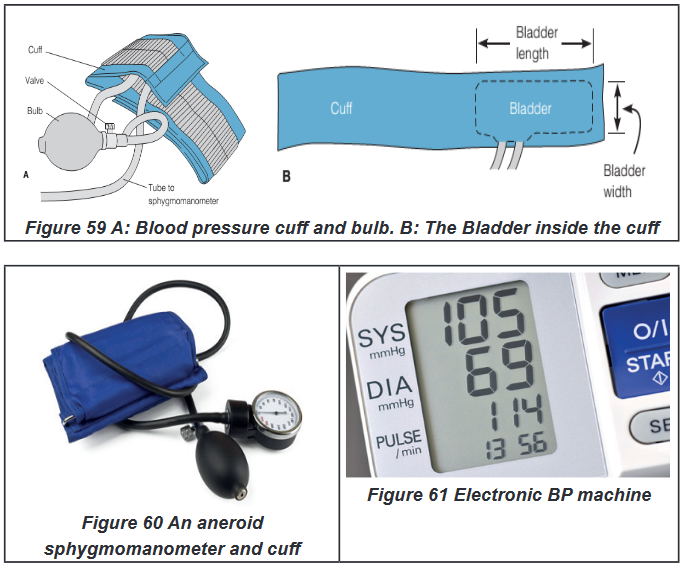

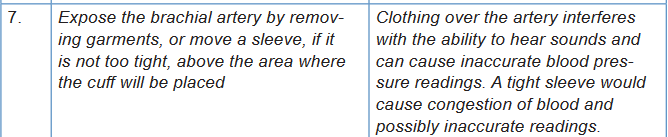

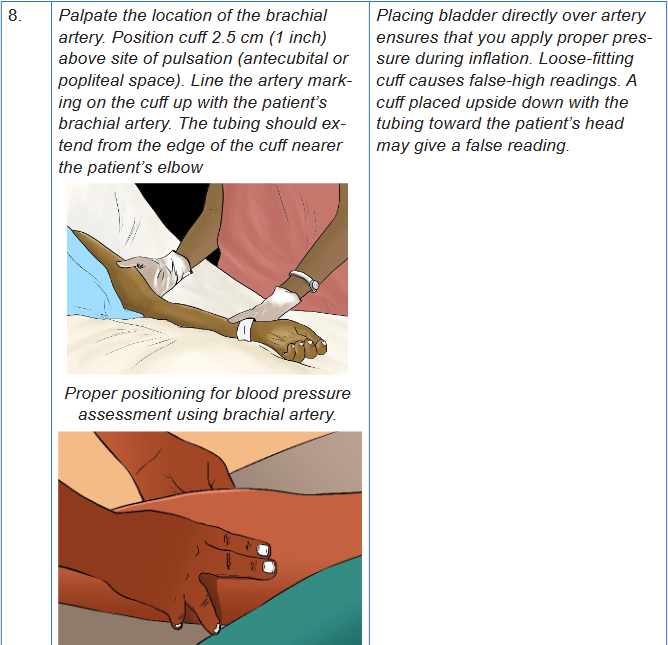

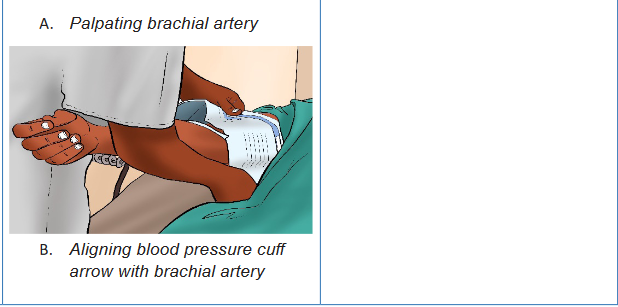

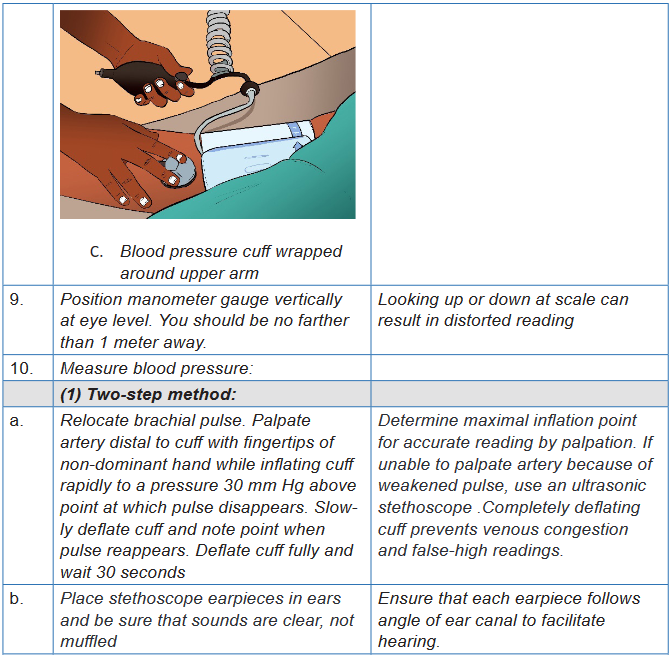

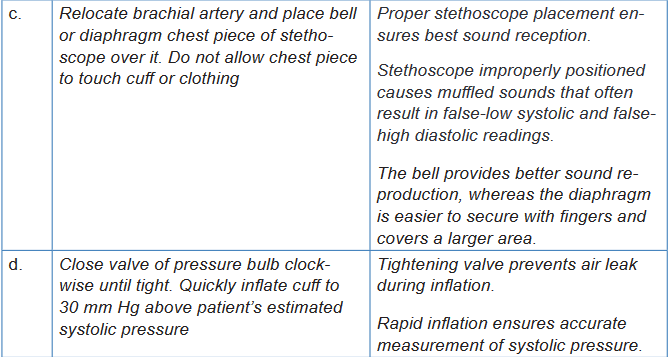

Blood pressure is measured with a blood pressure cuff, a sphygmomanometer

and a stethoscope. The blood pressure cuff consists of the bladder; that is, a rubber

bag that can be inflated with air. It is covered with cloth and has two tubes attached

to it. One tube connects to a rubber bulb that inflates the bladder. A small valve

on the side of this bulb traps and releases the air in the bladder. The other tube is

attached to a sphygmomanometer. The sphygmomanometer indicates the pressure

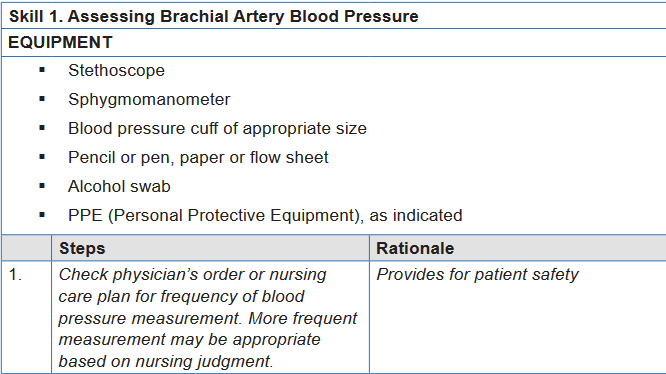

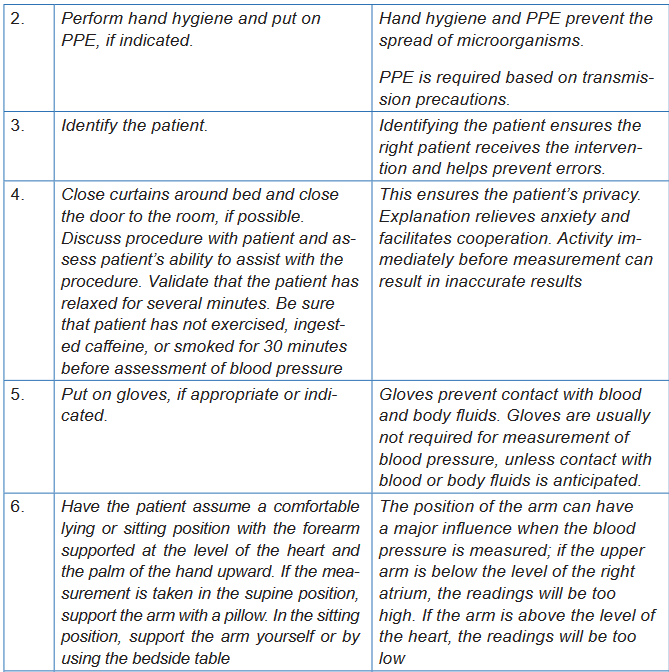

of the air within the bladder. There are two types of sphygmomanometers: aneroid

and digital (electronic).The aneroid sphygmomanometer is a calibrated dial with a needle that points to the

calibrations. Most clinical settings use digital (electronic) sphygmomanometers;

however, manual blood pressure measurements are more reliable and

accurate than electronic blood pressure devices, which need to be calibrated

regularly for accuracy. All health care facilities should have manual blood pressure

equipment available for use

Self -assessment 3.4.

For Blood pressure overview:

1) What is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure?

2) What are the five determinants of blood pressure?

3) The following blood pressures in mmHg, taken 6 months apart, were

recorded from adult patients screened by the nurse at the health center.

Which patient should be referred to the physician for hypertension

evaluation?

Patient 1: 120/80, 118/78, 124/82

Patient 2: 128/84, 124/86, 128/88

Patient 3: 148/82, 148/78, 134/86

Patient 4: 154/78, 118/76, 126/84

4) Explain why the blood pressure increases with age?For Blood pressure measurement:

For you to master the technique of blood pressure measurement; go back to

your previous groups of two; let each student measures one more time the

blood pressure of his /her partner. The teacher will be facilitating and observing

each student while carrying out the procedure.

1) Record the results

2) Interpret the results.

3) Communicate results to your partner.3.5. Respiration

Learning activity 3.5.

For overview

Use the provided book of Fundamentals of Nursing to read the materials on

Respiration under the vital signs unit and make a summary note of the following:

1) Definition of Respiration

2) Normal values and abnormal values of Respiration

3) Pathological variations of Respiration

4) (Risk) Factors affecting Respiration

5) Sites of pulse

6) Different methods of Respiration taking or How to assess the Respiration:

7) Basic nursing interventions during abnormal respiration or in case of

respiration alterations?For procedure

Using checklist provided and equipment for respiration rate taking (see checklist);

read all steps of pulse rate taking in order for you to measure correctly the

Respiration rate for your partner. Remember that you need a watch, a pen and

a sheet paper. Go back to your groups of 2 students and each one of you do

the following

• Observe this image of a nurse assessing respirations of the patient.

• Position your pair in the supine or sitting position and

• Measure his/her respiration rate and vice-versa

• Compare your results.

3.5.1. Respiration Overview

Respiration is the interchange of oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) between

the atmosphere and the body and involves both external respiration and internal

respiration.External respiration is the exchange of these gases between the lungs’ alveoli and

the blood found in the capillaries that surround the alveoli.Internal respiration is the process of exchanging gases between the circulating

blood and the tissue cells that make up the body.The movement of air into and out of the lungs is known as ventilation. The

mechanics of respiration involve the act of breathing in, termed as inhalation or

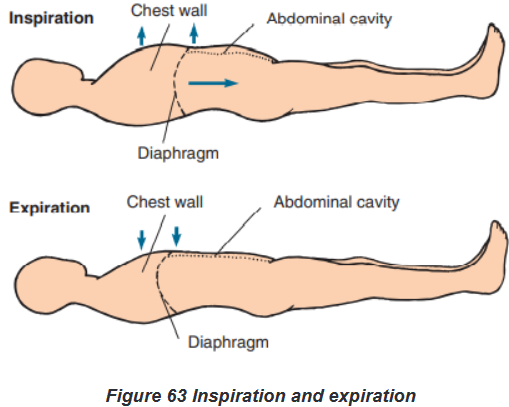

inspiration, and breathing out, described as exhalation or expiration.a. Inspiration

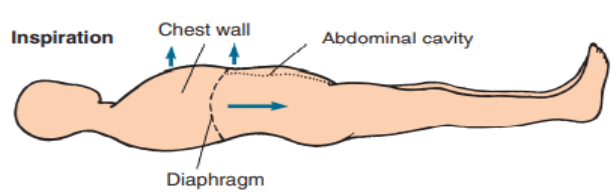

To effect inspiration, the medulla sends an impulse via the phrenic nerves to the

diaphragm muscle and along the intercostal nerves to the intercostal muscles,

telling the muscles to contractThe contraction of the diaphragm causes it to flatten and move downward, while

the contraction of the inter-costal muscles results in pulling the ribs upward and

outward, enlarging the chest cavity.b. Expiration

Once the medulla stops sending the motor impulses to inhale, the intercostal and

diaphragm muscles begin to relax, once again shrinking the thoracic or chest

cavity to the smaller, pre-inhalation state and compressing the lungs. The elastic

connective tissue of the alveoli recoils somewhat like a rubber band, forcing the air

that is mostly CO2 out of the alveoli so that it can be exhaled and returned to the

atmosphere.c. Rate

Each respiration consists of one inspiration and one expiration. Observe the rise

and fall of the chest or abdomen to count the rate.

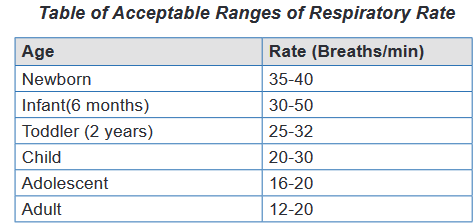

d. Normal and Abnormal values

The normal rate for adults is between 12 and 20 bpm. When the rate, depth,

rhythm, pattern, and respiratory effort fall within normal parameters, the term

eupnea is used to describe the respirations.

Bradypnea describes a respiratory rate below 12 respirations per minute; when

the rate exceeds 20 respirations per minute, the term is tachypnea. These are

abnormal values. When the breathing rate slows, it results in a decreased intake

of O2 that can result in a deficiency of O2 in the tissues and cells. When respirations

cease or are absent, this is known as apnea. You have only a brief window of 3 to

5 minutes in which to restore respirations before brain damage and death occur.Other things to consider when assessing respiration rate

Assess respiration for:

Rate per minute

Depth

Rhythm

Pattern

Respiratory effortRespiratory Effort

Respiratory effort refers to the amount of work required to breathe. Normally, the

act of breathing is effortless and is performed unconsciously. An individual who is

having labored or difficult breathing is said to be having dyspnea. Another sign

of difficult breathing is use of the accessory respiratory muscles: the neck and

abdominal muscles. It is important to assess which activities result in dyspnea,

document findings in the patient’s record, and report such findings to the supervisor.Some patients find it too difficult to breathe unless positioned in an upright position,

such as sitting or standing. This condition is known as orthopnea. In other words,

we define “Orthopnea” as an abnormal condition in which a person must sit or

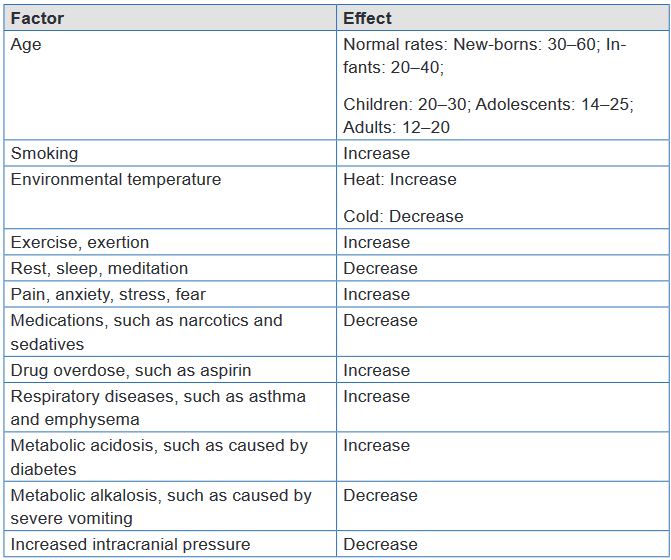

stand to breathe deeply or comfortablye. Factors affecting Respiratory rate

Because the heart and lungs work together to provide circulation of nutrients and

oxygen, the factors that affect the heart rate generally affect the respiratory rate as

well. For example, as fever raises the pulse rate, it will also increase the respiratory

rate. Breathing speeds up in an attempt to meet the body’s increased metabolic

needs and to remove excess heat. For every 1°F rise in body temperature, the

respiratory rate increases approximately four breaths per minute. The table below

presents further factors that affect the respiratory rate.

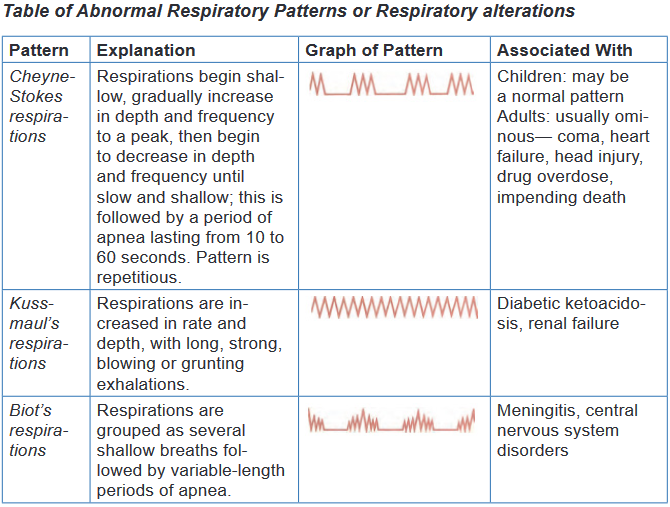

f. Pathological (abnormal) variations of Respiration rate

Some patients find it too difficult to breathe unless positioned in an upright position,

such as sitting or standing. This condition is known as orthopnea. In other words,

we define“Orthopnea” as an abnormal condition in which a person must sit or stand to

breathe deeply or comfortably.

g. Sites of Respiration rate taking

The rate is usually measured when a person is at rest and simply involves counting

the number of breaths for one minute by counting how many times the chest rises.

Note depth of respirations by observing degree of chest wall movement while

counting rate. In addition, assess depth by palpating chest wall excursion or

auscultating posterior thorax after you have counted rate. See Fig.5-8

h. Basic Nursing interventions in case of respiratory alterations

In cases of: Apnea: You have only a brief window of 3 to 5 minutes in which to restore

respirations before brain damage and death occur. Call for help to start

Cardio Pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) Dyspnea: Patients with dyspnea experience more distress when lying flat.

Placing the patient in a semi-Fowler or Fowler position facilitates a better

respiratory pattern. Maximal lung expansion can be achieved by having

the patient assume a sitting position, leaning forward over a raised bedside

table with arms resting on the table, in what is called the tripod position.

People who have difficulty ventilating all areas of their lungs, those whose

gas exchange is impaired or people with heart failure may benefit from

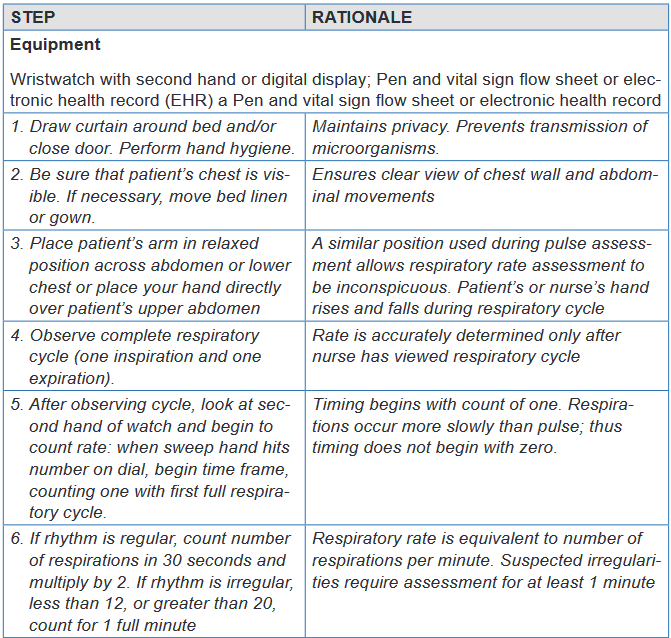

oxygen therapy to prevent hypoxia3.5.2. Measurement of respirations

a) Methods of Respiration taking /How to assess Respiration

The only equipment required to assess respiration is a watch.

BOX 3.5.2.

N.B. Because individuals can voluntarily control their breathing for short

intervals of time:

• It is better to assess the respirations without the patient’s awareness.

• This may be accomplished by positioning the patient’s arm across his or

her chest or abdomen.

• Feel for the radial pulse and hold the pulse site while you assess first the

respirations and then the radial pulse. It will appear that you are simply

taking the patient’s pulse, and this will help to distract the patient from

concentrating on his or her breathing.

• While pressing two fingers against the pulse site, count the respiratory

rate for 30 seconds and multiply times two for a 1-minute rate, and then

continue to palpate the radial pulse site to assess the pulse rate.

• If the patient is critically ill or respirations deviate in any manner from

the norm, assess for a full minute.

• Without special equipment, you can only observe the rise and fall of

the chest to provide a subjective measurement of the depth, usually

described as shallow, normal, or deep.b) Respiratory rate assessment procedure

The checklists that will help student to acquire the skills of respiration rate taking

by following all steps and procedures are hereby provided:

Self -assessment 3.5.

For Overview

1) What are the normal values or acceptable ranges of respiration rate for:

new-born, Infant (6 months), Toddler, Child, adolescent and Adult?

2) Explain the following terms:

a) Bradypnea and tachypnea;

b) Apnea, dyspnea, orthopnea

3) Name at least four abnormal Respiratory patterns

4) Identify at least five factors affecting Respiratory rate.

5) Provide the definition of the terms: Respiration, External respiration and

Internal respiration

6) Indicate the sites used for Respiration rate takingFor Measurement Procedure:

Instructions:

For you to master the technique of Respiration rate taking; going back to your

previous groups of two; let each student takes one more time the respiration

rate of his /her partner.

The teacher will be facilitating and observing each student while carrying out

the procedure by doing the following:

1) Take correctly the Respiration rate of your partner

2) Record the results

3) Interpret them.

4) Communicate results to your partner.3.6. Oxygen saturation (Pulse Oximetry)

Learning activity 3.6.

In small groups of four (4) learners per each, use the provided Fundamentals

of Nursing book and read especially the material and procedural guide on

measurement of oxygen saturation (Pulse Oximetry) under vital signs unit.

After getting an overview information related to the meaning of pulse oximetry,

normal values, factors that may affect the oxygen saturation readings and the

equipment used to measure the oxygen saturation; two learners will pair and

every one will measure the oxygen saturation of his/her partner, write down the

results and interpret themPulse oximetry is the indirect measurement of oxygen saturation and is the

fifth vital sign. During ventilation, oxygen and carbon dioxide diffuse across the

alveolar capillary membrane. Each alveolus is a collection of air sacs surrounded

by a network of capillaries carrying arterial blood from the right ventricle. The

diffusion of these gases occurs in the alveoli and these gases diffuse from the area

of high concentration to the area of low concentration. There is a net movement of

oxygen from the air sacs into the alveolar capillaries, thereby increasing the oxygen

concentration of the blood in these capillaries. This arterial blood has a high carbon

dioxide concentration which diffuses from the alveolar capillaries into the air sacs.Oxygen is carried in the blood as either dissolved oxygen or as oxygen bound

to haemoglobin in red blood cells. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in the

plasma is represented as the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2). In

contrast, the saturation of arterial oxygen (SaO2) is a ratio of the oxygen bound

to haemoglobin compared with the oxygen-carrying capacity of the haemoglobin.After oxygen diffuses from the alveoli into the pulmonary blood, most of the oxygen

attaches to hemoglobin molecules in red blood cells. Red blood cells carry the

oxygenated hemoglobin molecules through the left side of the heart and out to the

peripheral capillaries, where the oxygen detaches, depending on the needs of the

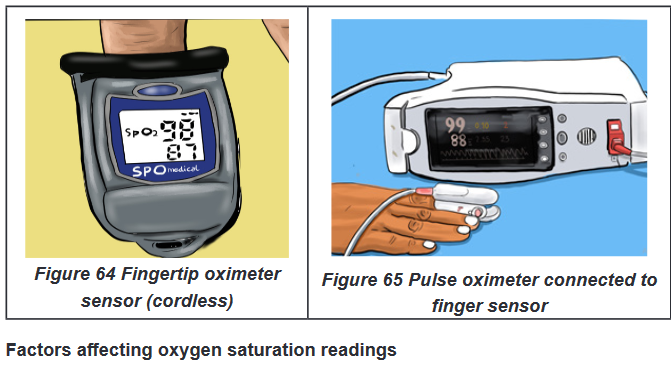

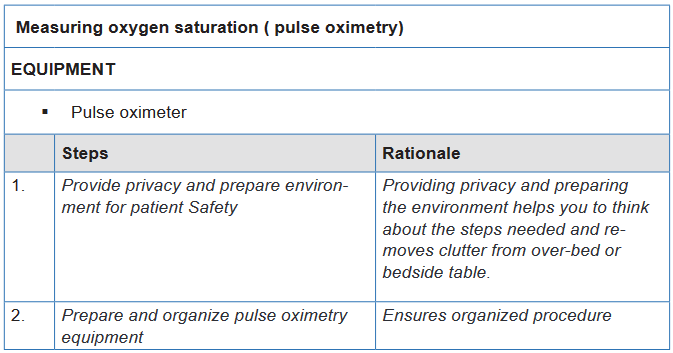

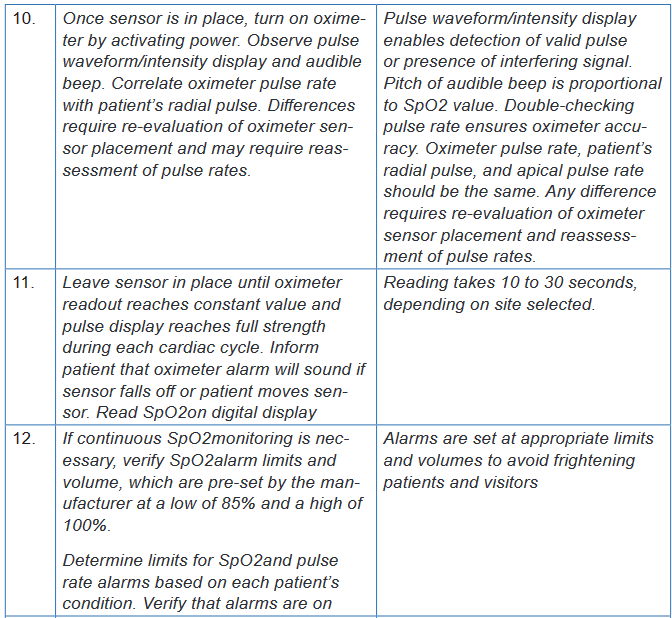

tissues.A pulse oximeter is a non-invasive device that estimates a person’s arterial blood

oxygen saturation (SaO2) by means of a sensor attached to the person’s finger,

toe, nose, earlobe or forehead (or around the hand or foot of a neonate). The pulse

oximeter can detect hypoxaemia before clinical signs and symptoms such as

cyanosis (dusky/darker) skin colour and dusky nail bed colour) develop. Oxygen

saturation assessed using the invasive approach is documented as SaO2 (arterialoxygen saturation); oxygen saturation assessed by pulse oximetry is documented

as SpO2 (peripheral oxygen saturation or tissue oxygenation).The oximeter

calculates the pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2). SpO2 is a reliable estimate of SaO2.

More specifically, SpO2 is the percentage of oxygenated hemoglobin (hemoglobin

containing oxygen) compared with the total amount of hemoglobin in the blood.

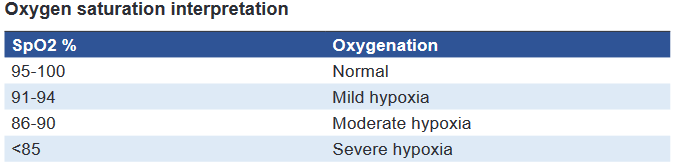

Normally SpO2 is between 95% and 100%; however, in patients with extensive

respiratory disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), SpO2

greater than 90% may be an acceptable baseline.

Note: Oximetry measurements should always be interpreted in conjunction with

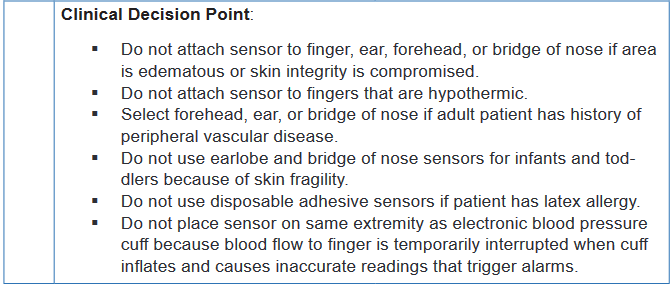

other patient factors, including signs and symptoms of hypoxiaThe pulse oximeter’s sensor has two parts: (a) two light-emitting diodes (LEDs)—

one red, the other infrared—that transmit light through nails, tissue, venous blood,

and arterial blood; and (b) a photodetector placed directly opposite the LEDs (e.g.,

the other side of the finger, toe, or nose). The photodetector measures the amount

of red and infrared light absorbed by oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in

peripheral arterial blood and reports it as SpO2.

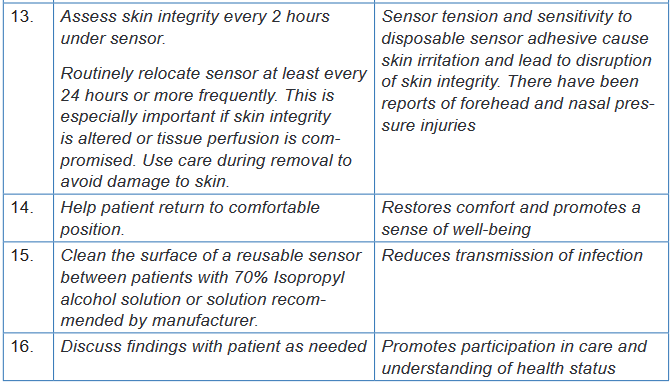

Hemoglobin. If the hemoglobin is fully saturated with oxygen, the SpO2will appear

normal even if the total hemoglobin level is low. Thus, the person could be severely

anemic and have inadequate oxygen to supply the tissues but the pulse oximeter

would return a normal value.Circulation. The oximeter will not return an accurate reading if the area under the

sensor has impaired circulation, such as occurs in peripheral vascular disease or if a

person is very cold. Other factors that result into reduction of pulse volume (reduction

of arterial pulsations) will also affect the oxygen saturation reading. Such factors

are peripheral vascular disease (atherosclerosis), hypothermia, pharmacological

vasoconstrictors (epinephrine, phenylephrine, and dopamine), low cardiac output

and hypotension, peripheral edema, tight probe (will record venous pulsations in

the finger that compete with arterial pulsations).Activity. Shivering or excessive movement of the sensor site may interfere with

accurate readings.Dark-colored nail polish or discoloration of the nail bed. False readings

typically arise when a person is wearing dark colored nail polish or if the nail bed

is discolored by a subdermal hematoma or other sources of nail bed discoloration,

such as nicotine stains.Carbon monoxide poisoning. Pulse oximeters cannot discriminate between

hemoglobin saturated with carbon monoxide versus oxygen. In this case, other

measures of oxygenation are needed.

Self-assessment 3.6.

An Associate Nurse (AN) reports to the charge nurse that a patient’s pulse

oximeter machine continues to alarm with a reading of 88%. The charge nurse

enters the room and assesses for signs and symptoms of alterations in oxygen

saturation and finds none.

1) What action does the nurse take next?

1) Remove the current machine from service and ask the AN to use

another pulse oximeter device

2) Verify that the patient’s oxygen device and flow are correct

3) Verify that the oximeter sensor is intact and the skin under the sensor

is dry

4) Notify the health care provider immediately

2) What are the signs and symptoms of alterations in oxygen saturation?3.7. Parameters

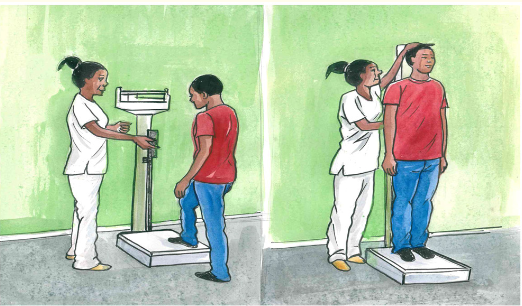

Learning activity 3.7.

Observe the images above provided in your textbook under the vital signs

unit and parameters and after reading the sub-topic on Weight and Height

measurement; make a summary note of the following:

1) Definition of two parameters (Height and Weight)

2) Importance of Measuring Height and Weight

3) Specific reasons for weighing both a child and an adult

4) Identify material /equipment used to measure weight and HeightUsing procedural guide provided and equipment/Materials for Weight and

Height measurement; read all steps in order for you to measure correctly the

Weight and Height for your partner in the previous groups of two students. Go

back to your groups and each one of you do the following:

i. Position your partner in position

ii. Measure his/her Weight and Height and vice-versa

iii. Compare your results3.7.1. Weight and Height overview

Introduction and importance of weight and height

Measuring height and weight is as important as assessing the client’s vital signs.

Routine measurement provides data related to growth and development in infants

and children and signals the possible onset of alterations that may indicate illnessin all age groups. The client’s height and weight are routinely taken upon admission

to acute care facilities and during visits to prescribing practitioners’ offices, clinics,

and other health care settings.a) Weight

Weight is the quantitative expression of body that indicates the state of growth and

health measured in kg or grams.Materials/Equipment: A well weighing scale (for adults); Baby Weighing Machine

or Salter balance, a pen and weight recording flow sheetThe Purpose of weight measurement

The purpose is to obtain accurate weight of the patient, to aid in accurate diagnosis

of the patient’s condition, to evaluate the patient’s response to treatmentSpecific reasons for weighing

In a child: reasons are to follow up a good growth, to appreciate the nutritional

state, to follow the evolution of an illness, and to calculate some doses of medicineIn adult: reasons are to evaluate the patient’s general state, to help in the orientation

of the diagnosis, to inform on the evolution of the illness, to calculate doses of some

medicines, to follow up the evolution of treatment and to follow up the pregnant

womanb) Size/Height

It is the measurement from head to toe that indicates the state of growth and health

and is commonly expressed in centimeters (cm), or meters (m). In some countries;

measurement of height is also expressed in inches (in.), feet (ft).Guidelines:

The scale for measuring height, calibrated in either centimeters or meters,

is usually attached to a standing weight scale.

The metal rod attached to the back of the scale should be extended to

gently rest on top of the client’s head, and the measurement should be read

at eye level.

Have the patient’s shoes/slippers removed while taking height to avoid any

variations in the reading

If thick object is placed on the top of head at right angle to the scale indicating

the reading, note the bottom reading of the object.

The nurse should ask the client to stand erect on the scale’s platform.Equipment/Materials

A scale for measuring height

A standing weight scale.

The metal rod

Pen and Height recording flow sheetIndications:

Follow up of child growth

To measure the nutritional status.BOX 3.7.1.

Height increases gradually from birth to the pre-pubertal growth spurt. Girls

usually reach their adult height between the ages of 16 and 17 years, whereas

boys usually continue to grow until the ages of 18 to 20 years. The older adult

usually decreases in height as a result of a gradual loss of muscle mass and

changes in the vertebrae that occur in condition such as osteoporosis (a

process in which reabsorption exceeds accretion of bone).Use the patient’s weight and height measurements to calculate the patient’s

BMI. Weight in kilograms Body mass index height in meter (Additional

information to the teacher)Rationale: BMI is an indicator of total body fat stores in the general population

and provides a more accurate weight calculation than weight measurement

alone. In addition, it provides an estimation of risk for diseases, such as heart

disease, diabetes, and hypertension.3.7.2. Measurement of Weight and Height Procedures

a) Conditions required for weighing:

i. In adult:

The weighing scale must be well-designed and well controlled, that means

graduated on zero: very important!

It must be put on a plane surface

The patient must remove the shoes and must be undressed while only

keeping light clothes in order to reduce the weight He must stand up, free hands and does not hold any object

Weight must be taken regularly

ii. In childThe weight of a child can be taken, according to age with: Baby Weighing Machine

or Salter balance. If it is not available:

Weigh the mother and the child and to note the weight;

Weigh only mother

Then make the difference between the first weight and the second, what

corresponds approximately to the child’s weight.

c) Procedure for weight and height measurementi. Equipment /Materials:

A scale for measuring height

A standing weight scale.

The metal rod

Pen and Height recording flow sheetWhen measuring an infant’s height,

The nurse should place the infant on a firm surface.

Extend the knees, with the feet at right angles to the table.

Measure the distance from the vertex (top) of the head to the soles of the

feet with a measuring tape.N.B. The procedure usually requires two nurses, one to hold the infant still and

the other to measure the length. If the nurse needs to perform the measurement

without assistance, an object should be placed at the infant’s head, the infant’s

knees should be extended, and a second object should be placed at the infant’s

feet. Lift the infant and measure the distance between the two objects.For Adults measurement,

With shoes off, and standing erect

Measure the patient’s height using a wall-mounted measuring device or

measuring pole.

Compare height and weight with recommended average weights on a

standardized chart.Rationale: Ratio of height and weight is a general assessment of overall health,

hydration, and nutrition.Self-Self -assessment 3.7.

For Overview: Section (a)

1) Define the two parameters: Weight and Height/size

2) Explain the Purpose of weight measurement

3) What are the specific reasons for weighing both a child and an adult

4) List all materials used measuring Weight and Height both for Adult and

a childFor Weight and Height Measurement Procedure: Section (b)

Instructions:

For you to master the technique of Weight and Height measurement; going

back to your previous groups of two; let each student measures one more time

the Weight and Height of his /her partner. Be familiar with the use of the check-

list provided to you.End unit assessment 3

Question one

Mr. K is 25 years old male from a low income family. He consults the nearest

health center complaining of vomiting and diarrhea. During initial assessment

data collection, Mr. K tells to the nurse that it is the 3rd day having both vomiting

and diarrhea (vomiting: 4 times a day and diarrhea: 6 times a day), severely

nauseated and dizzy, tolerating sips of clear fluid. No past history of medications

and illnesses.

Think about these data from Mr. K and try to answer the following questions:

1) What infection control measures should the nurse implement?

2) What route should be used to measure body temperature for Mr. K?

3) Identify in the above case study the factors that may affect the pulse

and blood pressure of Mr. KQuestion two

During physical examination of Mr. K, the nurse measures his vital signs and

parameters and notes the following findings: Temperature: 102.20 F, Pulse: 120

bpm (radial), BP: 98/68 mmHg, RR: 22 bpm irregular rhythm, Sp02: 94%, Weight:

53kg, Height: 174cm. Reflect on these findings and respond to the following

questions:

1) Which findings are considered abnormal for Mr. K? What medical

terminologies are used to define/label the abnormal findings?

2) The nurse uses the two-step method of blood pressure assessment to

obtain accurate measurements for Mr. K. The nurse is explaining the

steps of this procedure to the associate nurse. Place the steps in correct

order:

a) Place stethoscope in ears and place the diaphragm of stethoscope

over the brachial artery

b) Palpate brachial artery while inflating blood pressure cuff 30mmHg

over the pulse disappearance.

c) Note point where you hear first Korotkoff sound.

d) Deflate cuff fully and wait 30 seconds

e) Apply blood pressure cuff 2.5cm above brachial artery.

f) Continue to deflate cuff until sound disappears.

g) Quickly inflate cuff to 30 mm Hg above patient’s estimated systolic

pressure

h) Slowly deflate cuff and note point when pulse reappears.