UNIT 8 DIGNITY AND SELF-RELIANCE

Key Unit Competence:

To be able to critique how the home-grown solutions contribute to self-reliance

(Abunzi, Gacaca, Girinka, Ingando, Imihigo, Itorero, Ubudehe, Umuganda,

umwiherero)

Introductory activity

Discuss how Rwandan people were handling their problems in

traditional society in different domains such as medicine, education,

agriculture, justice, leisure, arts, handcraft and environment and then

propose which methods from Rwandan traditional society should be

applied to our modern society to handle problems. Write your answer

on not more than one page.

8.1. Concepts of home-grown solutions and self-reliance

Learning activity 8.1

1. Examine in which context Rwanda has initiated her proper

innovations such as Gacaca, Abunzi, Itorero, Umwiherero and

Girinka to achieve economic and social development and write

your response in not more than 15 lines.

2. Read and use your knowledge on Umuganda to comment on the

following statement:

“Our country was once known for its tragic history. Today, Rwanda is

proud to be known for its transformations…When your achievements

are a result of hard work, you must be determined to never slide back

to where you once were… What we have achieved to date shows us

what we are capable of and Umuganda is an integral part of achieving

even more…Umuganda is one of the reasons we are moving forward,

working together and believing in our common goal of transforming

our lives and the lives of our families”, President P. Kagame at Nderaon October 30, 2015

8.1.1. Home-grown solutions initiatives

Home-Grown Initiatives (HGIs) are Rwanda’s brain child solutions to economic

and social development. They are practices developed by the Rwandan

citizens based on local opportunities, cultural values and history to fast track

their development. Being locally created, HGIs are appropriate to the local

development context and have been the bedrock to the Rwandan development

successes for the last decade.

HGIs are development/governance innovations that provide unconventional

responses to societal challenges. They are based on:

• National heritage/legacy

• Historical consciousness

• Strive for self-reliance

HGIs include Umuganda (community work), Gacaca (truth and reconciliation

traditional courts), Abunzi (mediators), Imihigo (performance contracts), Ubudehe

(community-based and participatory effort towards problem solving), Itoreroand

Ingando (solidarity camps), Umushyikirano (national dialogue), Umwiherero

(National Leadership Retreat) and Girinka (One cow per Family program).

They are all rooted in the Rwandan culture and history and therefore easy to

understand by the communities.

Self-reliance: This is a state of being independent in all aspects. Theindependence could be social, political or economic.

8.1.2 Abunzi Community mediators

The word “abunzi” can be translated as “those who reconcile” or “those who

bring together” (from verb kunga). In the traditional Rwanda, abunzi were men

and women for their integrity and were asked to intervene in the event of conflict.

Each conflicting party would choose a person considered trustworthy, known as

a problem-solver, who was unlikely to alienate either party. The purpose of this

system was to settle disputes and also to reconcile the conflicting parties and

restore harmony within the affected community.

Abunzi can be seen as a hybrid form of justice combining traditional with modern

methods of conflict resolution. The reintroduction of the Abunzi system in 2004

was motivated in part by the desire to reduce the accumulation of court cases,

as well as to decentralise justice and make it more affordable and accessible

for citizens seeking to resolve conflicts without the cost of going to court. Today,

Abunzi is fully integrated into Rwanda’s justice system.

a) Conflict resolution through community participation

Historically, the community, and particularly the family, played a central role in

resolving conflicts. Another mechanism for this purpose was inama y’umuryango

(meaning ‘family meetings or gatherings) in which relatives would meet to find

solutions to family problems. Similar traditions existed elsewhere, such as the

“dare” in Zimbabwe. These traditional mechanisms continue to play important

roles in conflict resolution regarding land disputes, civil disputes and, in some

instances, criminal cases.

The adoption of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms in Rwanda emerged

from the recognition of a growing crisis in a judiciary where it had become almost

impossible to resolve disputes efficiently and in a cost-effective manner. The

Government of Rwanda concluded that modern judicial mechanisms of dispute

resolution were failing to deliver and so the decision was taken to examine

traditional mediation and reconciliation approaches as alternatives. By doing so,

it would not only help alleviate the pressure on conventional courts but also align

with the policy objective of a more decentralized justice system. In addition, the

conflict resolution mechanisms rooted in Rwandan culture were perceived as less

threatening, more accessible and therefore more intimate. Those who referred

their cases to Abunzi were more comfortable seeking mediation from within their

community, which afforded them a better understanding of the issues at hand.

b) Establishment of the mediation committees (Abunzi committee)

In 2004, the Government of Rwanda established the traditional process of abunzi

as an alternative dispute resolution mechanism. Established at the cell and sector

levels, abunzi primarily address family disputes, such as those relating to land

or inheritance. By institutionalizing Abunzi, low level legal issues could be solved

at a local level without the need to be heard in conventional courts. Citizens

experiencing legal issues are asked to first report to abunzi, cases not exceeding

3,000,000 Frs (for land and other immovable assets) and 1,000,000 Rwf (for

cattle and other movable assets). Cases of these types can only be heard in a

conventional court if one party decides to appeal the decision made at the sector

level by the mediation committee.

As the Abunzi system gained recognition as a successful method to resolve

conflict and deliver justice, the importance of providing more structure and

formality to their work increased. Consequently, the abunzi started receiving

trainings on mediating domestic conflicts and support from both governmental

and non-governmental organisations to improve the quality of their mediation

services.

8.1.3 Gacaca Community courts

The word gacaca refers to the small clearing where a community would traditionally

meet to discuss issues of concern. People of integrity (elders and leaders) in the

village known as inyangamugayo would facilitate a discussion that any member of

the community could take part in. Once everyone had spoken, the inyangamugayo

would reach a decision about how the problem would be solved. In this way,

Gacaca acted very much as a traditional court. If the decision was accepted by all

members of the community, the meeting would end with sharing a drink as a sign

of reconciliation. If the parties were not happy with the decision made at Gacaca,

they had the right to take their case to a higher authority such as a chief or even

to the king.

One aspect particular to traditional Gacaca is that any decision handed down at

the court impacted not only the individual but also their family or clan as well. If

the matter was of a more serious nature and reconciliation could not be reached,

the inyangamugayo could decide to expel the offenders or the members of their

group from the community.

The most common cases to come before Gacaca courts were those between

members of the same family or community. It was rare for members of other

villages to be part of the courts and this affirmed the notion of Gacaca as a

community institution.

Colonisation had a significant impact on the functioning of Gacaca and in 1924

the courts were reserved only for civil and commercial cases that involved

Rwandans. Those involving colonisers and criminal cases were processed under

colonial jurisdiction. While the new justice systems and mechanisms imported

from Europe did not prohibit Gacaca from operating, the traditional courts saw

far fewer cases. During the post-colonial period, the regimes in power often appointed administrative officials to the courts which weakened their integrity

and eroded trust in Gacaca.

The Genocide against the Tutsi in 1994 virtually destroyed all government and

social institutions and Gacaca was no different. While Gacaca continued after the

Genocide, its form and role in society had been significantly degraded.

a) Contemporary Gacaca as a home-grown solution

Contemporary Gacaca was officially launched on June 18, 2002 by President

Paul Kagame. This took place after years of debate about the best way to give

justice to the survivors of the Genocide and to process the millions of cases that

had risen following the Genocide.

Contemporary Gacaca draws inspiration from the traditional model by replicating

a local community-based justice system with the aim of restoring the social

fabric of the society. In total, 1,958,634 genocide related cases were tried

through Gacaca. The courts are credited with laying the foundation for peace,

reconciliation and unity in Rwanda. The Gacaca courts officially finished their work

ten years later on June 18, 2012.

Gacaca first began as a pilot phase in 12 sectors across the country one per

each province as well as in the City of Kigali. After the pilot, the courts were

implemented across the country and the original Organic Law No. 40/2000

(January 26, 2001) was replaced by the Organic Law No. 16/2004 (June 19,

2004) which then governed the Gacaca process.

b) The aims of the contemporary Gacaca

– Expose the truth about the Genocide against the Tutsi

– Speed up genocide trials

– Eradicate impunity

– Strengthen unity and reconciliation among Rwandans

– Draw on the capacity of Rwandans to solve their own problems.

These aims were carried out at three levels of jurisdiction: the Gacaca Court of

the cell, the Gacaca Court of the Sector, and the Gacaca Court of appeals. There

were 9013 cell courts, 1545 Sector courts and 1545 Courts of Appeal nationwide.

According to the statistics given by National service of Gacaca Courts, the Gacaca

Courts were able to try 1,958,634 cases of genocide within a short time (trials

have begun on to 10/3/2005 in pilots sectors). This is on irrefutable evidence of

the collective will and ability of Rwandans to overcome huge challenges of their

country and work for its faster development basing on “Home grown solutions”.

8.1.4 Girinka Munyarwanda- One Cow per Poor Family

Programme

The word girinka (gira inka) can be translated as “may you have a cow” and

describes a centuries’ old cultural practice in Rwanda whereby a cow was

given by one person to another, either as a sign of respect and gratitude or as a

marriage dowry.

Girinka was initiated in response to the alarmingly high rate of childhood

malnutrition and as a way to accelerate poverty reduction and integrate livestock

and crop farming.

The programme is based on the premise that providing a dairy cow to poor

households helps to improve their livelihood as a result of a more nutritious and

balanced diet from milk, increased agricultural output through better soil fertility

as well as greater incomes by commercializing dairy products.

Since its introduction in 2006, more than 203,000 beneficiaries have received

cows. Girinka has contributed to an increase in agricultural production in Rwanda

- especially milk products which have helped to reduce malnutrition and increase

incomes. The program aimed at providing 350,000 cows to poor families by 2017.

Traditional Girinka

Two methods, described below, come under the cultural practice known asgutanga inka, from which Girinka is derived.

Kugabira: Translated as “giving a cow”; such an act is often done as a sign of

appreciation, expressing gratitude for a good deed or to establish a friendship.

Ubuhake: This cultural practice was a way for a parent or family to help a son

to obtain a dowry. If the family was not wealthy or did not own cattle, they could

approach a community or family member who owned cows and requested him/

her to accept the service of their son in exchange for the provision of the cows

amounting to the dowry when the son marries. The aim of ubuhake was not only

to get a cow but also protection of a cow owner. This practice established a

relationship between the donor and beneficiary. An informal but highly valued

social contract was established which was fulfilled through the exchange of

services such as cultivating the farm of the donor, looking after the cattle or

simply vowing loyalty.

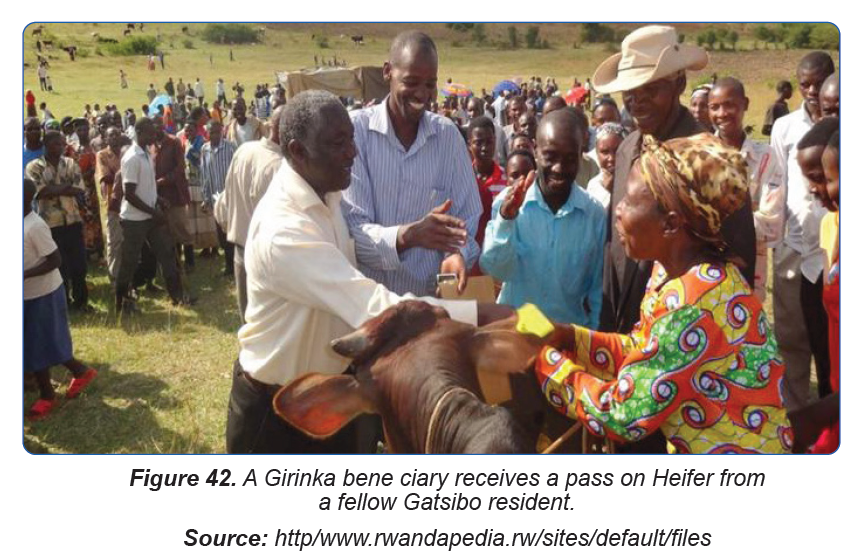

Contemporary Girinka

Girinka was introduced in 2006 against a backdrop of alarmingly high levels of

poverty and childhood malnutrition. The results of the Integrated Household

Living Conditions Survey 2 (EICV 2) conducted in 2005 showed rural poverty at

62.5%. The Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CFSVA)

and Nutrition Survey showed that 28% of Rwanda’s rural population were foodinsecure

and that 24% of the rural population were highly vulnerable to food

insecurity.

The objectives of the programme are as follows:

• Reducing poverty through dairy cattle farming.

• • Improving livelihoods through increased milk consumption and income

generation.

• Improving agricultural productivity through the use of manure as fertilizer.

• Improving soil quality and reducing erosion through the planting of grasses

and trees.

Promoting unity and reconciliation among Rwandans based on the cultural

principle that if a cow is given from one person to another, it establishes trust,

respect and friendship between the donor and the beneficiary. While this was

not an original goal of Girinka, it has evolved to become a significant aspect of theprogram.

Girinka has been described as a culturally inspired social safety net program

because of the way it introduces a productive asset (a dairy cow) which can

provide long-term benefits to the recipient. Approved on 12 April 2006 by Cabinet

decision, Girinka originally aimed to reach 257,000 beneficiaries; however,

this target was revised upwards in 2010 to 350,000 beneficiaries by 2017. The

Government of Rwanda was initially the sole funder of the Girinka program but

development partners have since become involved in the program. This has led

to an increase in the number of cows being distributed.

Girinka is one of a number of programs under Rwanda’s Vision 2020, a set of

development objectives and goals designed to move Rwanda to a middle income

nation by the year 2020. By September 2014 close to 200,000 beneficiaries had

received a cow.

8.1.5. Ingando- solidarity camps

The word Ingando comes from the verb kugandika, which means going to stay in

a place far from one’s home, often with a group, for a specific reason.

Traditionally, the term ingando was used in the war context. It represented a

temporary resting place for warriors during their expeditions, or a place for the

king and the people travelling with him to stay. In these times of war, ingando

was the military camp or assembly area where troops received briefings on their

organisation and mission in preparation for the battle. These men were reminded

to put their differences behind them and focus on the goal of protecting their

nation.

The term Ingando has evolved in contemporary Rwanda to describe a place where

a group of people gather to work towards a common goal. Ingando trainings served

as think tanks where the sharing of ideas was encouraged. Ingando also included

an aspect of Umuganda. The trainings created a framework for the re-evaluation

of divisive ideologies present in Rwanda during the colonial and post-colonial

periods. Thus, ingando was designed to provide a space mainly for the young

people to prepare for a better future in which negative ideologies of the past

would no longer influence them.

The other aim of Ingando is to reduce fear and suspicion and encourage reconciliation

between genocide survivors and those whose family members perpetrated the

Genocide. Ingando trainings also serve to reduce the distance between some

segments of the Rwandan population and the government. Through Ingando,

participants learn about history, current development and reconciliation policies

and are encouraged to play an active role in the rebuilding of their nation.

8.1.6. Imihigo- performance contracts

The word Imihigo is the plural Kinyarwanda word of umuhigo, which means to vow

to deliver. Imihigo also include the concept of guhiganwa , which means to compete

among one another. Imihigo practices existed in pre-colonial Rwanda and have

been adapted to fit the current challenges of the Rwandan society.

Traditional Imihigo

Imihigo is a pre-colonial cultural practice in Rwanda where an individual sets

targets or goals to be achieved within a specific period of time. The person must

complete these objectives by following guiding principles and be determined to

overcome any possible challenge that arises. Leaders and chiefs would publicly

commit themselves to achieving certain goals. In the event that they failed, they

would face shame and embarrassment from the community. Definitions however

vary on what constitutes a traditional Imihigo. Some have recalled it as having a

basis in war, where warriors would throw a spear into the ground while publicly

proclaiming the feats they would accomplish in battle.

Contemporary Imihigo

Imihigo were re-initiated by Rwanda’s President, Paul Kagame, in March 2006.

This was as a result of the concern about the speed and quality of execution of

government programs and priorities. The government’s decentralisation policy

required a greater accountability at the local level. Its main objective was to

make public agencies and institutions more effective and accountable in their

implementation of national programs and to accelerate the socio-economic

development agenda as contained in the Vision 2020 and Economic Development

and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS) policies as well as the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs).

Today, Imihigo are used across the government as performance contracts and

to ensure accountability. All levels of government, from the local district level

to ministries and embassies, are required to develop and have their Imihigo

evaluated. Members of the public service also sign Imihigo with their managers orhead of institution.

8.1.7. Itorero: Civic education

Traditionally Itorero was a traditional institution where Rwandans would learn

rhetoric, patriotism, social relations, sports, dancing, songs and defence. This

system was created so that young people could grow with an understanding

of their culture. Participants were encouraged to discuss and explore Rwandan

cultural values. Itorero was reintroduced in 2009 as a way to rebuild the nation’s

social fabric and mobilise Rwandans to uphold important cultural values.

Traditional Itorero

As a traditional school, itorero trainers planned daily activities according to

different priorities and every newcomer in itorero had to undergo initiation, known

in Kinyarwanda as gukuramo ubunyamusozi. The common belief was that Intore

were different from the rest of the community members, especially in matters of

expression and behaviour because they were expected to be experts in social

relations, quick thinkers and knowledgeable.

Each Itorero included 40 to 100 participants of various age groups and had its

own unique name. The best graduates would receive cows or land as rewards.

The tradition of Itorero provided formative training for future leaders. These

community leaders and fighters were selected from Intore (individuals who took

part in Itorero) and were trained in military tactics, hand to hand combat, jumping,

racing, javelin, shooting and endurance. They were also taught concepts of

patriotism, the Rwandan spirit, wisdom, heroism, unity, taboos, eloquence,

hunting and loyalty to the army.

Itorero was found at three levels of traditional governance, the family, the chief,

and the king’s court. At the family level, both girls and boys would be educated

on how to fulfil their responsibilities as defined by the expectations of their

communities. For example, the man was expected to protect his family and the

country, while the woman was expected to provide a good home and environment

for her family. Adults were also asked to treat every child as their own in order to

promote good behavior among children.

At the chief level, a teenage boy was selected by either his father or head of the

extended family to be introduced to the chief so that he could join his Itorero.

Selection was based on good behavior among the rest of his family and his

community.

8.1.8. Ubudehe - Social categorisation for collective action and

mutual support

Ubudehe refers to the long-standing Rwandan practice and culture of collective

action and mutual support to solve problems within a community. It is one of

Rwanda’s best known Home-Grown Solution because of its participatory

development approach to poverty reduction. In 2008, the program won the United

Nations Public Service Award for excellence in service delivery. Today Ubudeheis one of the country’s core development programs.

The origin of the word Ubudehe comes from the practice of preparing fields

before the rainy season

and finishing the task in time for planting. A community would cultivate clear the

fields together to make sure everyone was ready for the planting season. Once

a community had completed Ubudehe for everyone involved, they would assist

those who had not been able to take part, such as the very poor. After planting

the partakers gathered and shared beer. Therefore, the focus of traditional

Ubudehe was mostly on cultivation. It is not known exactly when Ubudehe was

first practiced, but it is thought to date back more than a century.

At the end of a successful harvest, the community would come together to

celebrate at an event known as Umuganura. Everyone would bring something

from his/her own harvest for the celebrations. This event would often take place

once the community’s sorghum beer production was completed.

Ubudehe was an inclusive cultural practice involving men, women and members

of different social groups. As almost all members of the community took part, the

practice often led to increased solidarity, social cohesion, mutual respect and

trust.

8.1.9. Umuganda: Community work

In simple terms, the word Umuganda means community work. In traditional

Rwandan culture, members of the community would call upon their family, friends

and neighbors to help them complete a difficult task.

Umuganda can be considered as a communal act of assistance and a sign of

solidarity. In everyday use, the word ‘Umuganda’ refers to a pole used in the

construction of a house. The pole typically supports the roof, thereby strengthening

the house.

In the period immediately after independence in 1962, Umuganda was only

organised under special circumstances and was considered as an individual

contribution to nation building. During this time, Umuganda was often referred to

as umubyizi, meaning ‘a day set aside by friends and family to help each other’.

On February 2, 1974, Umuganda became an official government programme

and was organised on a more regular basis – usually once a week. The Ministry

of District Development was in charge of overseeing the program. Local leaders

at the district and village level were responsible for organisingUmuganda and

citizens had little say in this process. Because penalties were imposed for nonparticipation,

Umuganda was initially considered as forced labour.

While Umuganda was not well received initially, the programme recorded

significant achievements in erosion control and infrastructure improvement

especially building primary schools, administrative offices of the sectors and

villages and health centres.

After the Genocide, Umuganda was reintroduced to Rwandan life in 1998 as part

of efforts to rebuild the country. The programme was implemented nationwide

though there was little institutional structure surrounding the programme. It was

not until November 17, 2007 with the passing of Organic Law Number 53/2007

Governing Community Works and later on August 24, 2009 with Prime Ministerial

Order Number 58/03 (determining the attributions, organisation, and functioning

of community work supervising committees and their relations with other organs)

that Umuganda was institutionalised in Rwanda.

Today, Umuganda takes place on the last Saturday of each month from 8:00

a.m. and lasts for at least three hours. For Umuganda activities to contribute to

the overall national development, supervising committees have been established

from the village level to the national level. These committees are responsible

for organising what work is undertaken as well as supervising, evaluating andreporting what is done

Rwandans between 18 and 65 are obliged to participate in Umuganda. Those

over 65 are welcome to participate if they are willing and able. Expatriates living

in Rwanda are also encouraged to take part. Those who participate in Umuganda

cannot be compensated for their work – either in cash or in kind.

Today close to 80% of the Rwandans take part in monthly community work.

Successful projects have been developed for example the building of schools,

medical centres and hydro-electric plants as well as rehabilitating wetlands

and creating highly productive agricultural plots. The value of Umuganda to the

country’s development is very remarkable in many parts of the country.

While the main purpose of Umuganda is to undertake community work, it also

serves as a forum for leaders at each level of government (from the village up to

the national level) to inform citizens about important news and announcements.

Community members are also able to discuss any problems they or the community

are facing and to propose solutions together. This time is also used for evaluating

what they have achieved and for planning activities for the next Umuganda a

month later.

8.1.10. Umwiherero: National leadership retreat

Umwiherero, translated as retreat, refers to a tradition in Rwandan culture where

leaders convene in a secluded place in order to reflect on issues affecting their

communities. Upon return from these retreats, the objective is to have identified

solutions. On a smaller scale, this term also refers to the action of moving to a

quieter place to discuss issues with a small group of people.

For a few days every year, leaders from all arms of Government come under

one roof to collectively look at the general trajectory the country is taking and

seek remedies to outstanding problems. Initially, Umwiherero had been designed

exclusively for senior public officials but it has evolved to include leaders from

the private sector as well as civil society. Provided for under the constitution,

Umwiherero is chaired by the Head of State and during this time, presentations

and discussions centre on a broad range of development challenges including

but not limited to the economy, governance, justice, infrastructure, health and

education.

Since its inception, organizers of Umwiherero have adopted numerous innovative

initiatives to expedite the implementation of resolutions agreed upon at each

retreat. Since then, the results are quantifiable. These efforts have resulted in

noticeable improvements in planning, coordination, and accountability leading to

clearer and more concise priorities.

As discussions go deep in exposing matters affecting the well-being of the people

of Rwanda, poor performers are reprimanded and those who delivered on theirmandate are recognized.

Umwiherero provides a platform for candid talk among senior officials. For

example, an official raises a hand to mention his/her superior who is obstructing a

shared development agenda. The said superior is then given a chance to explain

to the meeting how he/she intends to resolve this deadlock.

Application Activity 8.1

1. Use your own words to explain the following concepts of homegrown

solutions: umuganda, imihigo and ubudehe.

2. Compare the traditional umuganda and contemporary umuganda.

3. Discuss the reason why Rwanda adopted home-grown solutions

to social and economic development.

8.2 Contribution of the home grown solutions towards a good

governance, self-reliance and dignity

Learning activity 8.2

“Akimuhana kaza imvura ihise” in English: help from neighbours

never comes in the rain it comes after. Discuss this Kinyarwanda

proverb in reference to the concepts of home-grown solutions

As part of the efforts to reconstruct Rwanda and nurture a shared national

identity, the Government of Rwanda drew on aspects of Rwandan culture

and traditional practices to enrich and adapt its development programmes to

the country’s needs and context. The result is a set of Governance and Home

-Grown Initiatives (GHI) - culturally owned practices translated into sustainable

development programmes.

As the abunzi system gained more recognition as a successful method to resolve

conflicts and deliver justice, the importance of providing more structure and

formality to their work increased.

During the fiscal year ending June 2017 for example, mediation committees

received 51,016 cases. They were composed of 45,503 civil cases representing

89.1% and 5,513 penal cases received before the amendment of the law

determining organization, jurisdiction, and competence and functioning of

mediation committees. A total of 49,138 cases equivalent to 96.3% were handled

at both sector and cell levels. 38,777 (76.0%) cases received by mediation

committees were handled at cell level, 10,361 (20.3%) cases were mediated

at sector level whereas only 3.6% were undergoing at the end of the year. The

number of cases received by mediation committees increased at the rate of

30.9% over the past three years.

The Rwanda Governance Board (RGB) conducted an investigation into public

perceptions of some of the benefits of Abunzi in comparison to ordinary courts.

Those surveyed highlighted the following positive attributes:

• The reduction of time spent to settle cases (86.7%).

• Reduction of economic costs of cases (84.2%);

The cultural based policies have contributed a lot in helping getting some socioeconomic

solutions that were not possible to get otherwise.

8.2.1. Contribution of Gacaca courts

Gacaca courts officially finished their work on June 18, 2012 and by that time

a total of 1,958,634 genocide related cases were tried throughout the country.

As earlier mentioned Gacaca is credited with laying the foundation for peace,

reconciliation and unity in Rwanda.

8.2.2 Impact of Girinka

Girinka has led to a number of significant changes in the lives of the poorest

Rwandans. The impact of the program can be divided into five categories including

agricultural production, food security, livestock ownership, health outcomes, unity

and reconciliation.

Agricultural production

Girinka has contributed to an increase in agricultural production in Rwanda,

especially milk products. Milk production has risen due to an increase in the

number of cows in the country and because beneficiaries have received cross

breeds with better productive capacity than local cattle species. Between 2000

and 2011, milk production increased seven fold allowing the Government of

Rwanda to start the One Cup of Milk per Child program in schools. Between 2009

and 2011, national milk production increased by 11.3%, rising to 372.6 million

litres from 334.7 million litres. Over the same period, meat production increased

by 9.9%, according to the Government of Rwanda Annual Report 2010-2011.

The construction of milk collection centres has also increased and by February

2013, there were more than 61 centres operational nationwide with 25 more due

to be completed by the end of 2013.

Most of the beneficiaries produce enough milk to sell some at market, providing

additional income generation. The manure produced by the cows increases

crop productivity, allowing beneficiaries to plant crops offering sustenance and

employment as well as a stable income. Girinka has also allowed beneficiaries to

diversify and increase crop production, leading to greater food security.

Food Security

According to the Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis and

Nutrition Survey (CFSVA) conducted in March/April 2012, almost four in five

have workspace reserved for them and must share space with the staff from

cells and/or sectors offices; this sharing can sometimes result in the loss or mixup

of case les.

• Incentives: A number of mediators complained that the incentive promised

to them and their families in the form of “mutuelle de santé” (health insurance)

was not always forthcoming.

• Transportation for field visits: According to a study conducted by RCN

Justice & Démocratie in 2009, mediators complained about not always

being able to afford transportation to perform site visits when reviewing

cases. While each chairperson at the appeal level received a bicycle, it has

been recognised that field visits for all mediators have been very difficult in

some cases. This can result in delays in the mediation process.

• Communication facilities: To perform their duties, mediators have to

commu-nicate among themselves or with other institutions, but they are

not given a communication allowance. This proves problematic at times

and can lead to financial stress for some when they are obliged to use their

own money to contact for instance litigants and institutions.

8.2.3. Contribution of Imihigo

Since its introduction, Imihigo has been credited with improving accountability

and quickening the pace of citizen centred development in Rwanda. The practice

of Imihigo has now been extended to the ministries, embassies and public service

staff.

Once the compilation of the report on Imihigo implementation has been completed,

the local government entity presents it to stakeholders including citizens, civil

society, donors and others. After reviewing the results, stakeholders are often

asked to jointly develop a way forward and this can be done by utilising the Joint

Action Development Forums (JADF).

SACCOs (Savings and Credit Cooperatives) and payment of teachers’ salaries

and arrears: Good progress was made in mobilising citizens to join SACCOs

and reasonable funds were mobilised. Although most of the SACCOs obtained

provisional licenses from the National Bank of Rwanda to operate as savings

and credit cooperatives, they needed to mobilise more member subscriptions

in order to realize the minimum amount required to obtain full licenses. Most of

all SACCO at the sector level needed adequate offices. In addition great efforts

were made to ensure that teachers were paid their monthly salaries on time.

8.2.5. Impact of ingando

Ingando has contributed significantly to the national unity and reconciliation in

Rwanda. This is especially true for the early years of the programme(between

1996-1999) when most participants were returning combatants or Rwandans

afraid or unsure of their new government. Special attention was paid to social

justice and helping participants understand government strategies to improve

social welfare. This approach was key in ensuring that the progress made in

reconciliation was sustainable.

At a consultative forum in 2001, a number of observations were made that are

indicative of the progress towards national unity, reconciliation and development.

These included rejection of genocide ideology, a desire to be involved in

safeguarding national security and having equal access to education as well as

being part of the national army and the police force.

This consultative forum also gathered strong and positive recommendations

from Rwandans throughout the country on the necessity to teach love and

truth denounce wrongdoing and encourage forgiveness among people, foster

tolerance, promote the culture of peace and personal security, as well as

promoting development and social welfare for all Rwandans.

Between 1999 and 2010, more than 90,000 people took part in the Ingando

trainings organised by the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission.

8.2.6 Contribution of Itorero

The contribution of Itorero as a home-grown solution towards good governance,

self-reliance and dignity is observed through Itorero activities described above.

Capacity building for Itorero ry’Igihugu: structures of Intore were elected from

villages up to sector levels in 2009. Later on in 2012, Itorero ry’Igihugu was

officially launched in primary and secondary schools. From November 2007 up

to the end of 2012, Itorero ry’ Igihugu had a total of 284,209 trained Intore. The

number of Intore who have been trained at the Village level amounts to a total

of 814 587. Those mentored at the national level are the ones who go down

to mentor in villages, schools, and at various work places. In total, 1 098 599

Rwandans have been mentored nationwide.

Itorero ry’Igihugu was launched in all districts of the country. Each district’s

regiment presented their performance contracts at that colour ful ceremony

marked by cultural festivals. Each district’s Intore regiment publically announced

its identification name. At the national level, all the 30 district Intore regiments

comprised one national Itorero, but each district regiment has its identificationname. Each district regiment can have an affiliate sub-division which can, in turn,

also have a different identification name. There is also Itorero for Rwandans in

Diaspora that has the authority to develop its affiliated sub-division.

In order to enable each Intore to benefit and experience change of mindset,

each group chooses its identification name and sets objectives it must achieve.

Those projected objectives must be achieved during or after training, and this is

confirmed by the performance contracts that necessarily have to be accomplished.

With this obligation in mind, each individual also sets personal objective that in

turn contributes to the success of the corporate objectives.

8.2.6 The contribution of Ubudehe

Ubudehe has been recognized internationally as a highly successful development

program. In 2008, Ubudehe was awarded the United Nations “Better Management:

Better Public Service” Award.

One of the most significant impacts of Ubudehe is the way in which it has

transformed citizens’ engagement with their own development. Much of the

twentieth century in Rwanda was characterized by centralized planning and

delivery of services with little or no involvement from local communities. Ubudehe

has changed this and, coupled with decentralisation efforts, has changed the

way Rwandans participate in decision making processes that affect their lives.

Ubudehe has achieved almost nationwide coverage and communities across

Rwanda are now actively involved in developing their own social maps, visual

representations and collection of data to the extent of poverty in their village.

This information is used to determine national development objectives against

which the national government and its ministries are held accountable.

The way in which Ubudehe has brought communities together for collective

action based on their own priorities is also considered a major achievement of

the programme. The provision of a bank account to each community has enabled

thousands of community led actions such as purchasing livestock, undertaking

agriculture activities, building clean water facilities, classrooms, terraces, health

centres as well as silos for storing produce. In 2006-2007, 9,000 communities

undertook different projects through Ubudehe and in 2007-2008 that number rose

to 15,000. 2010 saw over 55,000 collective actions by communities with the

assistance of 30,000 Ubudehe facilitators.

At least 1.4 million people, around 20% of the population, have been direct

beneficiaries of Ubudehe. Between 2005 and 2008, around 50,000 people were

trained on Ubudehe concepts and procedures.

This has resulted in a greater level of skills available to the community at the local

level helping Ubudehe to be more effective.

5.2.7 Contribution of Umuganda

Umuganda is credited with contributing to Rwanda’s development, particularly in

the areas of infrastructure development and environmental protection. Common

infrastructure projects include roads (especially those connecting sectors),

bridges, heath centres, classroom construction (to support the 9 and 12) Years

of Basic Education programs), housing construction for poor and vulnerable

Rwandans (often to replace grass-thatched housing) and the construction of

local government offices and savings and credit cooperative buildings.

8.2.9 Impact of Umwiherero

For a few days every year, leaders from all arms of Government come under

one roof to collectively look at the general trajectory the country is taking and

seek remedies to outstanding problems. Initially, Umwiherero had been designed

exclusively for senior public officials but it has evolved to include leaders from

the private sector as well as civil society. Provided for under the constitution,

Umwiherero is chaired by the Head of State and during this time, presentationsand

discussions centre on a broad range of development challenges including but not

limited to the economy, governance, justice, infrastructure, health and education.

Since its inception, organizers of Umwiherero have adopted numerous innovative

initiatives to expedite the implementation of resolutions agreed upon at each

retreat. Since then, the results are quantifiable. These efforts have resulted in

noticeable improvements in planning, coordination, and accountability leading to

clearer and more concise priorities.

As discussions go deep in exposing matters affecting the well-being of the people

of Rwanda, poor performers are reprimanded and those who delivered on their

mandate are recognized.

Application activity 8.2

1. Analyze the impact of Abunzi as a home-grown initiative.

2. Discuss the contribution of home-grown initiatives to social and

economic development of Rwanda.

3. Analyze the contribution of home-grown initiatives to Unity and

Reconciliation of Rwandans.

8.3. Challenges encountered during the implementation of the home grown solutions.

Learning activity 8.3

Discuss in not more than 500 words challenges encountered in

Girinka programme and how they can be handled.

1. Analyse challenges encountered in the implementation of Gacaca

courts.

2. Using internet, reports, media and your own observation discuss

the challenges met by abunzi.

3. Discuss the key challenges in the Imihigo planning process and

implementation

4. Evaluate the role of umuganda as a home-grown solution.

8.3.1. Challenges of Abunzi

Some of the challenges encountered during the implementation of Abunzi

are:

• Inadequate legal knowledge: While most mediators acknowledged that

they received training session on laws, they expressed a desire to receive

additional training on a more regular basis to enhance their knowledge of

relevant laws.

• Insufficient mediation skills: Mediators also expressed a desire to

receive additional training in professional mediation techniques in order to

improve the quality and effectiveness of their work.

• Lack of permanent offices: In some areas, mediation committees do not

always have workspace reserved for them and must share space with the

staff from cells and/or sectors offices; this sharing can sometimes result in

the loss or mix-up of case

• Incentives: A number of mediators complained that the incentive promised

to them and their families in the form of “mutuelle de santé” (health

insurance) was not always forthcoming.

• Transportation for field visits: According to a study conducted by RCN

Justice &Démocratie in 2009, mediators complained about not always

being able to transportation to perform site visits when reviewing cases.

While each chairperson at the appeal level received a bicycle, it has been

recognised that field visits for all mediators have been very difficult in some

cases. This can result in delays in the mediation process.

• Communication facilities: To perform their duties, mediators have to

communicate among themselves or with other institutions, but they are not

given a communication allowance. This proves problematic at times and can lead to financial stress for some when they are obliged to use their own

money to contact for instance litigants and institutions.

8.3.2. Challenges of Gacaca courts

Below are challenges faced during implementation of Gacaca.

• At the beginning of the data collection phase at the national level, 46,000

Inyangamugayo representing 27.1% of the total number of judges, were

accused of genocide. This led to their dismissal from Gacaca courts.

• Leaders, especially in the local government, were accused of participating in

genocide constituting a serious obstacle to the smooth running of Gacaca.

• In some cases there was violence against genocide survivors, witnesses

and Inyangamugayo.

• Serious trauma among survivors and witnesses manifested during Gacaca

proceedings.

• In some cases there was a problem of suspects eeing their communities

and claiming that they were threatened because of Gacaca.

• In some cases there was corruption and favouritism in decision making.

8.3.3. Challenges of Girinka

The following are the major challenges faced by the Girinka programme:

In some cases, the distribution of cows has not been transparent and people

with the financial capacity to buy cows themselves were among the beneficiaries.

This issue was raised at the National Dialogue Council. (Umushyikirano) in 2009

and eventually resolved through the cow recovery programme. This program

resulted in 20,123 cows given to unqualified beneficiaries (out of a total of 20,532

wrongly given) redistributed to poor families.

8.3.4. Challenges of Ingando

Ingando has contributed significantly to national unity and reconciliation in

Rwanda. But when the programme was established, it faced significant challenges

including a lack of trust between participants and facilitators as well as low quality

facilities. These issues were slowly overcome as more resources were dedicated

to the programme.

8.3.5. Challenges of Ubudehe

The major challenges of Ubudehe can be divided into categorisation and project

implementation:

Categorisation

In some cases, village members have preferred to be classified into lower poverty

levels as a way to receive support from social security programs such as health

insurance and Girinka.

To overcome this, household poverty level categorisation takes place publically

with all heads of households and must be validated by the village itself.

In the event that community members dispute the decision made by their village,

they are entitled to lodge a complaint and appeal in the first instance to the

sector level. The Ubudehe Committee at the sector level conducts a visit to the

household and either upholds or issues a new decision. If community members

remain unhappy with the decision they can appeal in the second instance to the

district level. The final level of appeal is to the Office of the Ombudsman at the

central government level.

8.3.6. Challenges of Imihigo

While Imihigo has provided the Government of Rwanda and citizens with a way

to hold leaders to account, some challenges listed below have been identified

from the 2010-2011 evaluation report:

• There is a planning gap especially on setting and maintaining logic and

consistency: objectives, baseline, output/targets and indicators

• Setting unrealistic and over-ambitious targets by districts was common.

Some targets were not easily achievable in 12 months. For example,

construction of a 30 km road when no feasibility study had been conducted

or reducing crime by 100%.

• In some districts low targets were established that would require little e ort

to implement.

• The practice of consistent tracking of implementation progress, reporting

and ling is generally still weak.

• Some targets were not achieved because of district partners who did

not fulfill their commitments in disbursing funds - especially the central

government institutions and development partners.

• There is a weakness of not setting targets based on uniqueness of rural

and urban settings. Setting targets that are beyond districts’ full control was observed: For example,

construction of stadiums and development of master plans whose implementation

is fully managed by the central government.

There was general lack of communication and reporting of challenges faced that

hindered implementation of the committed targets.

8.3.7. Challenges of Itorero

During its implementation, Itorero faced a series of challenges including:

• Inadequate staff and insufficient logistics for the monitoring and evaluation

of Itorero activities;

• Low level of understanding the important role of Itorerory’ Igihugu on the

part of partners;

• Districts lack sufficient training facilities;

• Some Itorero mentors lack sufficient capacity to train other people;

• The National Itorero Commission does not get adequate information on

partners’

• commitment to Volunteer Services;

• A number of various institutions in the country have not yet started

considering voluntary and national service activities in their planning.

• Low understanding of the role of Itorero especially at the village level;

• Existence of some partners who have not yet included activities.

8.3.8. Challenges of Umuganda

The challenges faced by Umuganda fall into two broad categories: planning and

participation. In some areas of the country, poor planning has led to unrealistic

targets and projects that would be difficult to achieve without additional financing.

In urban areas, participation in Umuganda has been lower than in rural areas.

To address these challenges, the team responsible for Umuganda at the Ministry

of Local Government has run trainings for the committees that oversee Umuganda

at the local level.

These trainings include lessons on monitoring and evaluation, how to report

achievements, the laws, orders and guidelines governing Umuganda as well as

responsibilities of the committee.

To overcome the issues of low participation rates in some areas of the country,

especially in urban areas, an awareness raising campaign is conducted through

documentaries, TV and radio shows to inform Rwandans about the role Umuganda

plays in society and its importance.

8.3.9. Challenges of Umwiherero

The first four years of Umwiherero saw questionable results. The organisation

of the retreat was often rushed, objectives were poorly defined and few tangible

results could be measured.

This led President Paul Kagame to establish the Strategy and Policy Unit in

the Office of the President and the Coordination Unit in the Office of the Prime

Minister. At the same time, the Ministry of Cabinet Affairs was set up to improve

the functioning of the Cabinet. These two newly formed units were tasked with

working together to implement Umwiherero.

While the first retreat organised by the two new teams suffered from similar

problems to previous retreats, improvement was noticeable.

Following Umwiherero in 2009, Minister of Cabinet Affairs served as head of

the newly formed steering committee tasked with overseeing the retreat. The

steering committee was comprised of 14 team members. Alongside the steering

committee, working groups were set up to define the priorities to be included on

the retreat agenda. This process was overseen by the Strategy and Policy Unit

who developed a concept paper with eleven priority areas to be approved by the

Prime Minister and the President.

Since that time the organisation, implementation and outcomes of Umwiherero

have vastly improved and significant achievements have been recorded.

The focus on a small number of key priorities has made it easier for meaningful

discussions to be had and for effective implementation to take place. For example,

the number of national priorities agreed upon by participants fell from 174 in 2009

to 11 in 2010 and to six in 2011. The retreats are also credited with significantly

improving coordination and cooperation between government ministries and

agencies.

Application activity 8.3

1. Analyze challenges encountered in the implementation of Gacaca

courts.

2. Using internet, reports, media and your own observation discuss

the challenges met by abunzi.

3. Discuss the key challenges in the Imihigo planning process andimplementation.

8.4. End Unit Assessment

End Unit Assessment

1. Assess the achievements and challenges of Umuganda in

social and economic sector and propose what can be done to

improve it.

2. Explain the contribution and challenges of Umwiherero on

economic development and good governance and what can be

done to improve it.

3. Discuss the contribution of Ubudehe to dignity and self-reliance.

4. Analyse the contribution of Girinka to poverty reduction.

5. Discuss the social impact of Abunzi and its contribution to unityand reconciliation.