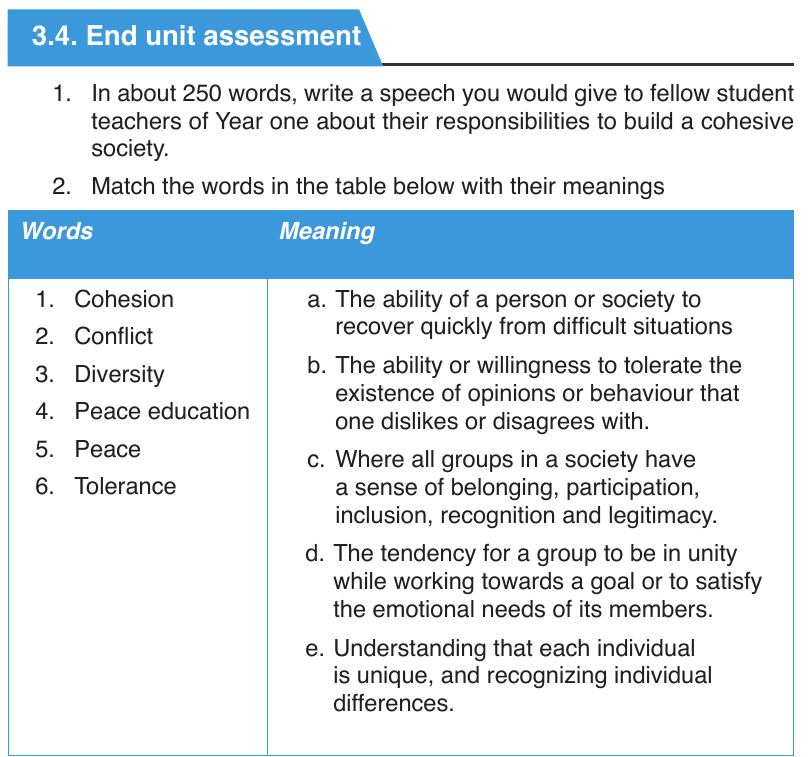

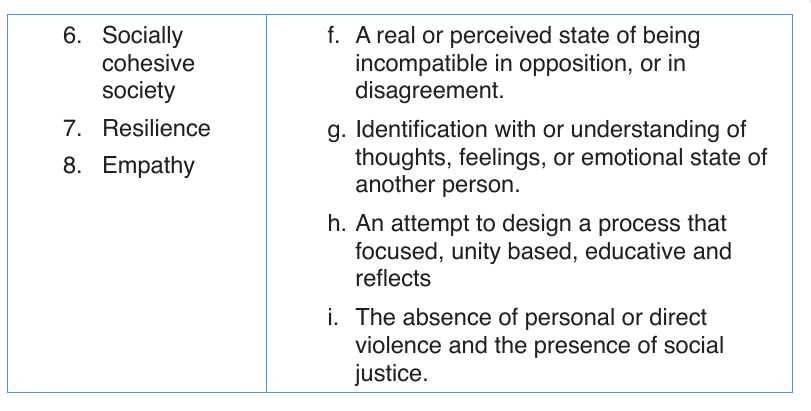

UNIT3: SOCIAL COHESION

3.1 Talking about personal values that enhance social cohesion.

3.1.1 Learning activity: reading and exploitation of the text

Text: The meaning of social cohesion within the Rwandan context

Within the official political discourse of the Rwandan government, the idea of social cohesion occupies a central place; it forms part of the set of national objectives of the Republic. Rwanda’s National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) defines social cohesion in terms of belonging, interpersonal trust and common values which are the “glue that bonds society together”. Similarly, a representative of the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG) described social cohesion in terms of “bringing back what did not exist any longer after genocide and about the capacity of Rwandans to redevelop unity”. Official discourse hence draws on

social psychological definitions. Aegis1 relies on a similar normatively infused definition of social cohesion: the Aegis Rwanda Youth Department coordinator summarised its meaning as an “understanding, [an] opening up to another person, what they have been through, and what they feel at the moment, like pain”, and the moral rules of ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s of a society. He equally drew on an empathy- based and normative value based approach. The Director of Aegis Rwanda also described social cohesion’s value as “bringing two broken entities back together”, by teaching skills on “how to live together”, and how to foster acommon understanding of “how the memory of the past informs the present and supports change in the future”. This is understandable in the specific context of a post-conflict setting. Peace building relies on the positive transformation or restoration of broken relationships between the people in conflict, “where divides are bridged and other negative relational attitudes and behaviours are broken in favour of positive ones” At no surprise, many ordinary citizens have internalised this type of social

psychological definition of social cohesion. Secondary students from Muhanga believe that social cohesion means “mutual respect, living in peace, having harmonious relationships in the community and families, helping and loving each other, having security and being co-dependent”. Kigali university

students equally refer to “good relationships and trust between members of a community, getting along with others, living together, united and in harmony, and working together to build the country [...] to work together and to achieve common goals despite the genocide history”.

Aegis Youth Programme participants emphasize the specificity of the post-conflict context where one needs to look “beyond the past” in order to rebuild society: “We are more than our past, our tribe. We are just people at the end of the day, there is more than our background [...]an environment [that] everybody feels part of [and] feels they belong...and which is peaceful, [a

society] that views people as people, that embraces difference. A society [in which] people feel accepted”.

As the Executive Secretary of the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, Habyarimana, emphasises “Rwandans have to be united in order to have a cohesive and peaceful society”. According to the Rwandan government, reconciliation entails “the formation or restoration of genuine peaceful relationships between societies that have been involved in intractable conflict, after its formal resolution is achieved”

By Nora Ratzmann

Adapted from http://www.genocideresearchhub.org.rw/app/uploads/2018/09/Nora-working-paper.pdf Comprehension questions

1. What do you understand by “the idea of social cohesion occupies a central place”?

2. How does the representative of the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide define social cohesion?

3. What is social cohesion’s value, according to the Director of Aegis Rwanda?

4. Why do you think all definitions of social cohesion in Rwandan context keep repeating the idea of restoring broken relationships or bringing back what did not exist any longer?

5. Enumerate at least 3 values that can enhance social cohesion.

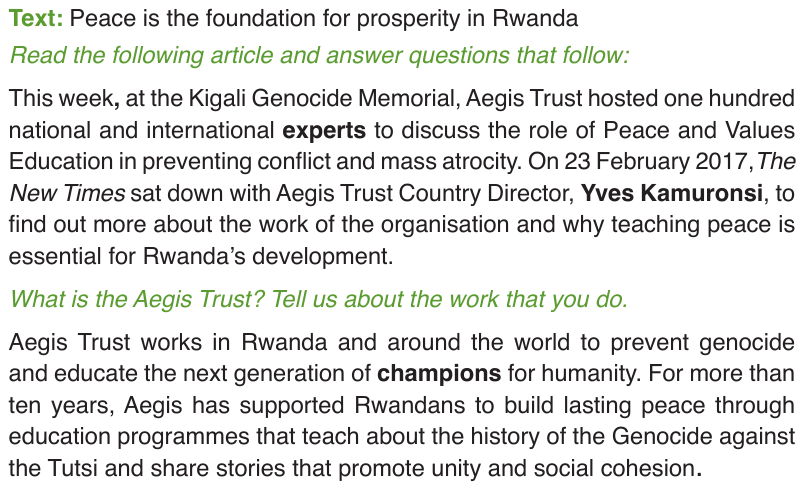

Why is peace and values education important?

Peace and stability are vital to the development of every community, city and country. If we live together in harmony, free from the fear of violence, then, we are able to create the prosperous lives we want and deserve.

In Rwanda, we know the terrible consequences of hatred and violence. The Genocide against the Tutsi was the result of a systematic campaign of dehumanisation and division over many years. Just as people were taught to hate one another, we can also teach people to love one another. When we teach peace, we develop a generation of peacemakers. While much progress has been made over the last 23 years, building peace is an on-going process and everyone needs to be involved – young and old. Whichever way you look at it, peace is the foundation for prosperity in Rwanda.

What impact is peace education having on the lives of Rwandans? Put simply, peace education is changing lives. We have seen Rwandans who harboured resentment against others begin the process of forgiveness and reconciliation.

For example, young people trained by Aegis Trust set up peace clubs and went door to door in their communities helping to solve family problems. One of these ‘Peace Champions’ in Gasabo District, Rameaux, was so inspired by what he learnt that he helped set up six other peace clubs and has run peace education workshops with more than 1,000 young people and community members.

What is your advice to young Rwandans wanting to build peace at home, school or in their communities?

You don’t need to be a grown up to be a champion for peace. It’s just about standing up for your values and what you believe in. For example, if a classmate is being bullied at school you can help them by telling the bully to stop it.

I would also encourage every young Rwandan to talk with their parents, teachers and friends if they see something they know isn’t right and work together to find a solution that works for everyone.

If anyone wants more support, they can visit the Peace School at the Kigali Genocide Memorial and talk to one of our team members.

Adapted from https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/208285 ;Comprehension questions

1. Why did one hundred national and international experts gather at the Kigali Genocide Memorial?

2. In not more than two lines, explain what the conversation between The New Times and Yves Kamuronsi was about.

3. Describe the duties of Aegis Trust.

4. How does peace and stability contribute to the development of every community?

5. In which way does Kamuronsi think we can develop a generation of peacemakers?

6. In one sentence explain how peace education changed the lives of Rwandans.

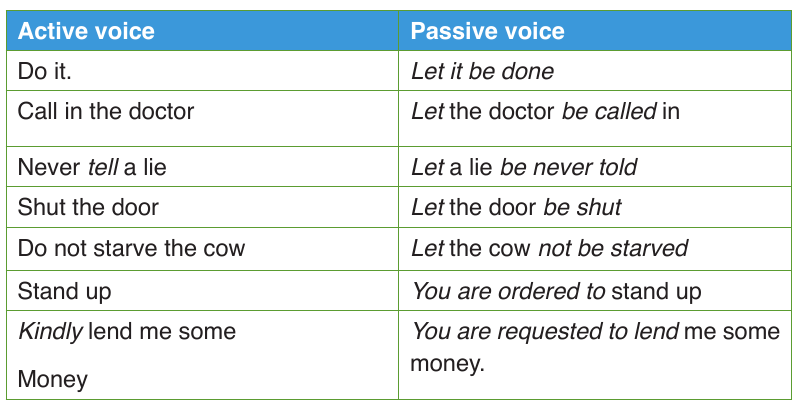

1. Identify the rules used to change active sentences into passive voices.

2. Why should we use the forms identified in the second column?

Notes

I. “By” is used in the passive voice when we want to mention the doer of the action.

Example: “Love addicted” was sung by Vamps.

II. Passive voice is used to show that we are not interested in the doer of the action.

Example: The streets are cleaned every day.

III. Passive voice is used when we do not know who performed the action.

Example: the answers have been filled in.

Ray’s calculator was made in Germany.

IV. Passive voice is used when we do not wish to mention the doer of the action.

Example: many problems have been ignored for too long.

Rules

1. The places of subject and object are interchanged i.e. the object shifts to the place of subject and subject shifts to the place of object in passive voice.

Example:

Active voice: I eat a banana.

Passive voice: A banana is eaten by me.

Subject (I) of sentence shifted to the place of object (banana) and object (banana) shifted to the place of subject (I) in passive voice.

2. Sometimes subject of sentence is not used in passive voice. Subject of sentence can be omitted in passive voice, if without subject it can give enough meaning in passive voice.

Example:

Passive voice: Animals are killed every day.

3. 3rd form of verb (past participle) is always used as main verb in sentences

of passive voice for all tenses. The base form of verb or present participle

will be never used in passive voice.

The word “by” is used before the subject in sentences in passive voice.

Example:

Active voice: He writes a sentence.

Passive voice: A sentence is written by him.

4. The word “by” is not always used before the subject in passive voice.

Sometimes words “with, to, etc” may also be used before the subject in

passive voice.

Examples:

Active voice: The water fills the tub.

Passive voice: The tub is filled with water.

Active voice: He knows me.

Passive voice: I am known to him.

3.3.2. Imperative Sentences

A. Definition

A sentence that expresses either a command, a request, a piece of advice,

an entreaty or desire is called imperative sentence.

B. Characteristics of Imperative Sentences

1. The object “you” is generally missing in Imperative Sentences. The structure of such sentences in Passive Voice is: Let + object + be/not be + V3

2. In sentences which express request, advice and order, such phrases as, you are requested to, /advised to /ordered to are used,

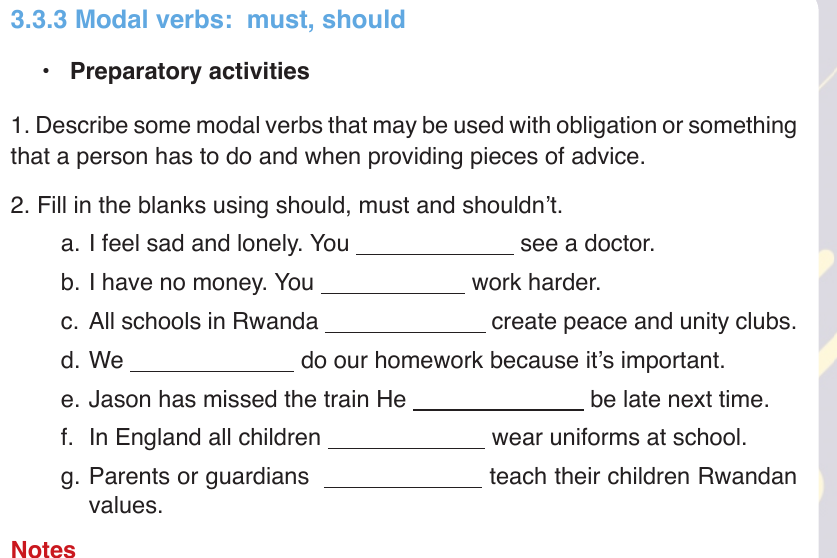

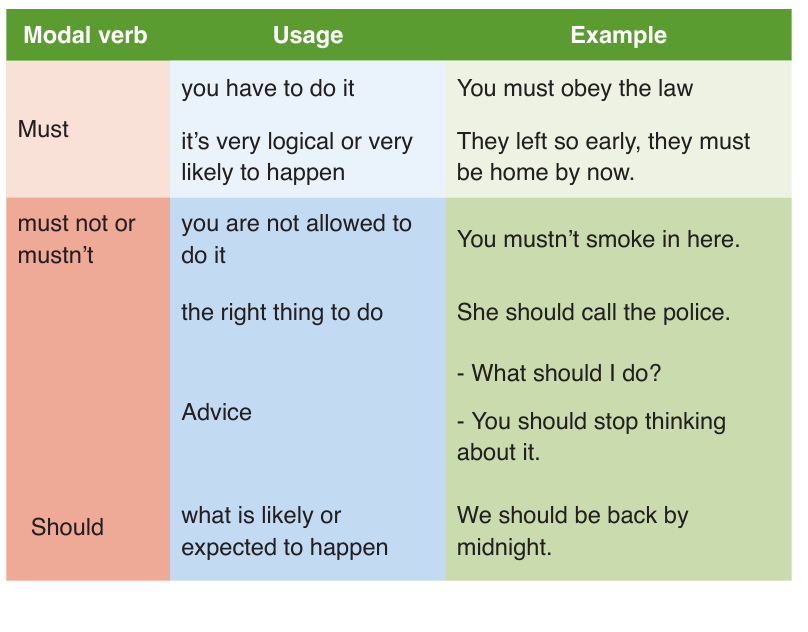

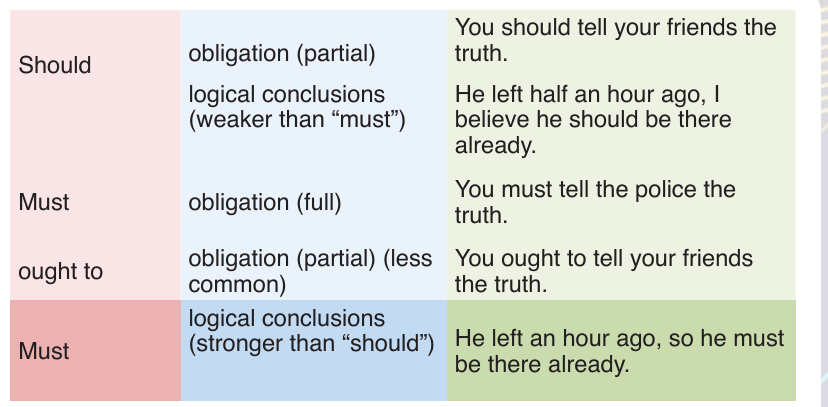

3. Word kindly /please is dropped.